Mei Ze (Chinese :梅賾; fl. 4th century), also known as Mei Yi (梅頤), was a Confucian scholar and government official of the Eastern Jin dynasty of ancient China. A native of Runan (汝南, present-day Wuchang District, Hubei province), Mei Ze served as governor of Yuzhang Commandery (豫章, present-day Nanchang, Jiangxi province). After the establishment of the Eastern Jin, he presented a purported copy of Kong Anguo's lost compilation of the Old Text Shangshu (Book of Documents) to the emperor, which became officially recognized as a Confucian classic for over a millennium. [1] However, Mei Ze's version of the Shangshu has been proven a forgery. [2]

Contents

Background

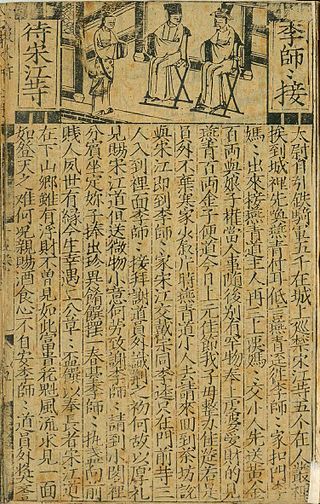

The Shangshu , a collection of documents written in the Zhou dynasty, is one of the Five Classics of Confucianism. Most copies of the book were destroyed in 213 BC, when the First Emperor of Qin ordered a large-scale burning of books. The scholar Fu Sheng hid a copy in the wall and later recovered 29 chapters of it, which is known as the "New Text" Shangshu. [2] During the early Western Han dynasty, another copy was accidentally discovered hidden in the walls of the mansion of Confucius, which contained 16 more chapters than Fu Sheng's version. Scholar Kong Anguo compiled and wrote a commentary of the document, and presented it to the emperor. This version is called the "Old Text" Shangshu, which was however lost during the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD). [2]

"Rediscovery" of the Old Text Shangshu

After the Yongjia Disturbance ended the Western Jin dynasty in 311 AD, the Jin court fled southeast to Jiankang. Emperor Yuan, the first emperor of Eastern Jin, asked the public to submit books to the court in order to replenish the imperial library which had been destroyed in the war. [1] Mei Ze presented a "rediscovered" copy of Kong Anguo's Old Text Shangshu to the emperor, along with a preface purportedly written by Kong. [3] Explaining the discovery, Mei Ze claimed that he acquired the documents from a certain Zang Cao (臧曹), who had previously obtained them from Liang Liu (梁柳), a cousin of the famous physician-scholar Huangfu Mi, and that he had salvaged the text from destruction in the warfare that ended the Western Jin. Zang Cao and Liang Liu had both been dead by the time Mei Ze presented the scripture to the emperor. [3] The Jin court accepted Mei's version as authentic, [4] [2] and it became widely disseminated throughout the empire. [5]

Mei Ze's version of the Shangshu includes Fu Sheng's New Text, which was redivided into 33 chapters, along with 25 extra chapters purportedly from Kong Anguo's lost Old Text, for a total of 58 chapters. [5]

Legacy

Mei Ze's Old Text Shangshu became highly influential. In the seventh century, during the early Tang dynasty, scholar Kong Yingda oversaw the imperial Correct Meanings of the Five Classics (五經正義) project, and Mei Ze's Old Text became the official version of the Confucian classic. The Shangshu Zhengyi, likely authored by Kong, provided the official interpretation of the text. [2] Although many scholars had questioned the authenticity of Mei's version over the centuries, it maintained its official status and was the most influential version of the Shangshu for more than 1,000 years until the Qing dynasty, [4] when the 17th-century scholar Yan Ruoqu devoted much of his lifetime to the study of the Shangshu and conclusively proved that Mei Ze's version was a forgery. [5] Analyses of the recently discovered Tsinghua Bamboo Slips have further bolstered Yan's now widely accepted conclusion. [6] [2]

Notes

- 1 2 "Mei Ze". Chinaknowledge.de. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Underhill 2013, p. 454.

- 1 2 Declercq 1998, p. 169.

- 1 2 Declercq 1998, p. 170.

- 1 2 3 伏胜 [Fu Sheng] (in Chinese). Guoxue.com. 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- ↑ Ed Zhang (2012-08-15). "Oldest Confucian classic is fake in parts". South China Morning Post . Retrieved 2013-05-19.

Related Research Articles

Jin Shengtan, former name Jin Renrui (金人瑞), also known as Jin Kui (金喟), was a Chinese editor, writer and critic, who has been called the champion of Vernacular Chinese literature.

Water Margin is one of the earliest Chinese novels written in vernacular Mandarin. It is one of the preeminent Classic Chinese Novels and is attributed to Shi Nai'an. It is also translated as Outlaws of the Marsh and All Men Are Brothers.

The Book of Documents, or the Classic of History, is one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature. It is a collection of rhetorical prose attributed to figures of ancient China, and served as the foundation of Chinese political philosophy for over two millennia.

The Book of Rites, also known as the Liji, is a collection of texts describing the social forms, administration, and ceremonial rites of the Zhou dynasty as they were understood in the Warring States and the early Han periods. The Book of Rites, along with the Rites of Zhou (Zhōulǐ) and the Book of Etiquette and Rites (Yílǐ), which are together known as the "Three Li (Sānlǐ)," constitute the ritual (lǐ) section of the Five Classics which lay at the core of the traditional Confucian canon. As a core text of the Confucian canon, it is also known as the Classic of Rites or Lijing, which some scholars believe was the original title before it was changed by Dai Sheng.

The burning of books and burying of scholars was the purported burning of texts in 213 BCE and live burial of 460 Confucian scholars in 212 BCE ordered by Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang. The events were alleged to have destroyed philosophical treatises of the Hundred Schools of Thought, with the goal of strengthening the official Qin governing philosophy of Legalism.

The Emperor in Han Dynasty, also released under the title The Emperor Han Wu in some countries, is a 2005 Chinese historical drama television series based on the life of Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty. It uses the historical texts Records of the Grand Historian and Book of Han as its source material.

In Chinese philology, the Ancient Script Classics refer to some versions of the Five Classics discovered during the Han dynasty, written in a script that predated the one in use during the Han dynasty, and produced before the burning of the books. The term became used in contrast with "Current Script Classics" (今文經), which indicated a group of texts written in the orthography currently in use during the Han dynasty.

The Four Books and Five Classics are authoritative and important books associated with Confucianism, written before 300 BC. They are traditionally believed to have been either written, edited or commented by Confucius or one of his disciples. Starting in the Han dynasty, they became the core of the Chinese classics on which students were tested in the Imperial examination system.

Mei is a romanized spelling of a Chinese surname, transcribed in the Mandarin dialect. In Hong Kong and other Cantonese-speaking regions, the name may be transliterated as Mui or Moy. In Vietnam, this surname is written as Mai. In romanized Korean, it is spelled Mae. The name literally translates in English to the plum fruit. The progenitor of the Méi clan, Méi Bo, originated from near a mountain in ancient China that was lined at its base with plum trees.

Fu Yue, also known as Hou Que, was an official who served as minister from Fuyan under the king Wu Ding 武丁 of the Shang 商 dynasty, who reigned around c. 1250–c. 1200 BCE. He has also been defined anachronistically a "premier."

The Yi Zhou Shu is a compendium of Chinese historical documents about the Western Zhou period. Its textual history began with a text/compendium known as the Zhou Shu, which was possibly not differentiated from the corpus of the same name in the extant Book of Documents. Western Han dynasty editors listed 70 chapters of the Yi Zhou Shu, of which 59 are extant as texts, and the rest only as chapter titles. Such condition is described for the first time by Wang Shihan in 1669. Circulation ways of the individual chapters before that point are subject to scholarly debates.

Fu is an ancient Han Chinese surname of imperial origin which is at least 4,000 years old. The great-great-great-grandson of the Yellow Emperor, Dayou, bestowed this surname to his son Fu Yi and his descendants. Dayou is the eldest son of Danzhu and grandson of Emperor Yao.

Yangzhou, Yangchow or Yang Province was one of the Nine Provinces of ancient China mentioned in historical texts such as the Tribute of Yu, Erya and Rites of Zhou.

Kong Anguo, courtesy name Ziguo (子國), Kong Anguo was a Chinese classicist, philosopher, and politician of the Western Han dynasty of ancient China. A descendant of Confucius, he wrote the Shangshu Kongshi Zhuan, a compilation and commentary of the "Old Text" Shangshu. His work was lost, but a debated fourth-century forgery was officially recognized as a Confucian classic for over a millennium.

Fu Sheng, also known as Master Fu (伏生), was a Chinese philosopher and writer. He was a Confucian scholar of the Qin and Western Han dynasties of ancient China, famous for saving the Confucian classic Shangshu from the book burning of the First Emperor of Qin. Fu Sheng is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu by Jin Guliang.

Mei Yi can refer to:

Zhang Zhupo, courtesy name Zide, also known as Daoshen, was an early Qing dynasty literary critic, commentator, and editor of fiction best known for his commentarial edition of the novel Jin Ping Mei.

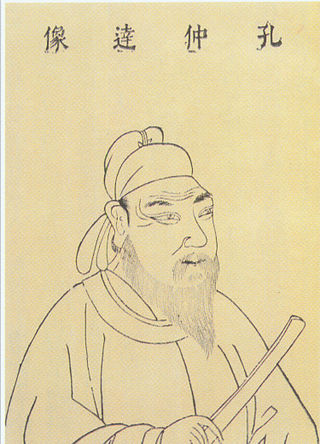

Kong Yingda, courtesy names Chongyuan (冲遠) and Zhongda (仲達), was a Chinese philosopher during the Sui and Tang dynasty. An ardent Confucianist, who is considered one of the most influential Confucian scholars in Chinese history. His most important work is the Wujing Zhengyi 五經正義, which became the standard curriculum for the imperial examinations, and the basis for all future official commentaries of the Five Classics. He was also "skilled at mathematics and the calendar."

Jia Kui, courtesy name Jingbo, was a Confucian philosopher who lived in the early Eastern Han period. He was a descendant of the Western Han politician and writer Jia Yi. He was born in Pingling (平陵), Youfufeng Commandery (右扶風郡), which is located northeast of present-day Xingping, Shaanxi. He studied at university in Luoyang.

Zhongshan Kingdom or Zhongshan Principality was a kingdom of the Han dynasty, located in present-day southern Hebei province.

References

- Declercq, Dominik (1998). Writing Against the State: Political Rhetorics in Third and Fourth Century China. Brill. ISBN 9789004103764.

- Underhill, Anne P. (2013). A Companion to Chinese Archaeology. Wiley. ISBN 9781118325728.

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.

Mei Ze | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Mei Yi |

| Academic background | |

| Influences | Fu Sheng Kong Anguo |