Mining is the extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agricultural processes, or feasibly created artificially in a laboratory or factory. Ores recovered by mining include metals, coal, oil shale, gemstones, limestone, chalk, dimension stone, rock salt, potash, gravel, and clay. The ore must be a rock or mineral that contains valuable constituent, can be extracted or mined and sold for profit. Mining in a wider sense includes extraction of any non-renewable resource such as petroleum, natural gas, or even water.

Open-pit mining, also known as open-cast or open-cut mining and in larger contexts mega-mining, is a surface mining technique that extracts rock or minerals from the earth.

Placer mining is the mining of stream bed deposits for minerals. This may be done by open-pit mining or by various surface excavating equipment or tunneling equipment.

Mining in the engineering discipline is the extraction of minerals from the ground. Mining engineering is associated with many other disciplines, such as mineral processing, exploration, excavation, geology, metallurgy, geotechnical engineering and surveying. A mining engineer may manage any phase of mining operations, from exploration and discovery of the mineral resources, through feasibility study, mine design, development of plans, production and operations to mine closure.

The tin mining industry on Dartmoor, Devon, England, is thought to have originated in pre-Roman times, and continued right through to the 20th century, when the last commercially worked mine closed in November 1930. From the 12th century onwards tin mining was regulated by a stannary parliament which had its own laws.

Gold mining is the extraction of gold by mining.

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines, also known as the Ogofau Gold Mine, are ancient Roman surface and underground mines located in the valley of the River Cothi, near Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire, Wales. The gold mines are located within the Dolaucothi Estate, which is owned by the National Trust.

Underground soft-rock mining is a group of underground mining techniques used to extract coal, oil shale, potash, and other minerals or geological materials from sedimentary ("soft") rocks. Because deposits in sedimentary rocks are commonly layered and relatively less hard, the mining methods used differ from those used to mine deposits in igneous or metamorphic rocks. Underground mining techniques also differ greatly from those of surface mining.

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture used in Rome was strongly influenced by Greek and Etruscan sources.

Mine exploration is a hobby in which people visit abandoned mines, quarries, and sometimes operational mines. Enthusiasts usually engage in such activities for the purpose of exploration and documentation, sometimes through the use of surveying and photography. In this respect, mine exploration might be considered a type of amateur industrial archaeology. In many ways, however, it is closer to caving, with many participants actively interested in exploring both mines and caves. Mine exploration typically requires equipment such as helmets, head lamps, Wellington boots, and climbing gear.

Las Médulas is a historic gold-mining site near the town of Ponferrada in the comarca of El Bierzo. It was the most important gold mine, as well as the largest open-pit gold mine in the entire Roman Empire. Las Médulas Cultural Landscape is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. Advanced aerial surveys conducted in 2014 using LIDAR have confirmed the wide extent of the Roman-era works.

The technology history of the Roman military covers the development of and application of technologies for use in the armies and navies of Rome from the Roman Republic to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The rise of Hellenism and the Roman Republic are generally seen as signalling the end of the Iron Age in the Mediterranean. Roman iron-working was enhanced by a process known as carburization. The Romans used the better properties in their armaments, and the 1,300 years of Roman military technology saw radical changes. The Roman armies of the early empire were much better equipped than early republican armies. Metals used for arms and armor primarily included iron, bronze, and brass. For construction, the army used wood, earth, and stone. The later use of concrete in architecture was widely mirrored in Roman military technology, especially in the application of a military workforce to civilian construction projects.

Mining was one of the most prosperous activities in Roman Britain. Britain was rich in resources such as copper, gold, iron, lead, salt, silver, and tin, materials in high demand in the Roman Empire. Sufficient supply of metals was needed to fulfil the demand for coinage and luxury artefacts by the elite. The Romans started panning and puddling for gold. The abundance of mineral resources in the British Isles was probably one of the reasons for the Roman conquest of Britain. They were able to use advanced technology to find, develop and extract valuable minerals on a scale unequaled until the Middle Ages.

The Tavistock Canal is a canal in the county of Devon in England. It was constructed early in the 19th century to link the town of Tavistock to Morwellham Quay on the River Tamar, where cargo could be loaded into ships. The canal is still in use to supply water to a hydro-electric power plant at Morwellham Quay, and forms part of the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Site. It is unusual for a canal, as it has a gentle slope over its length, resulting in a considerable flow of water.

Ancient Greek technology developed during the 5th century BC, continuing up to and including the Roman period, and beyond. Inventions that are credited to the ancient Greeks include the gear, screw, rotary mills, bronze casting techniques, water clock, water organ, the torsion catapult, the use of steam to operate some experimental machines and toys, and a chart to find prime numbers. Many of these inventions occurred late in the Greek period, often inspired by the need to improve weapons and tactics in war. However, peaceful uses are shown by their early development of the watermill, a device which pointed to further exploitation on a large scale under the Romans. They developed surveying and mathematics to an advanced state, and many of their technical advances were published by philosophers, like Archimedes and Heron.

Ancient Roman technology is the collection of techniques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices which supported Roman civilization and made possible the expansion of the economy and military of ancient Rome.

Fire-setting is a method of traditional mining used most commonly from prehistoric times up to the Middle Ages. Fires were set against a rock face to heat the stone, which was then doused with liquid, causing the stone to fracture by thermal shock. Rapid heating causes thermal shock by itself—without subsequent cooling—by producing different degrees of expansion in different parts of the rock. In practice, rapid cooling may or may not have been helpful to produce the desired effect. Some experiments have suggested that the water did not have a noticeable effect on the rock, but rather helped the miners' progress by quickly cooling down the area after the fire. This technique was best performed in opencast mines where the smoke and fumes could dissipate safely. The technique was very dangerous in underground workings without adequate ventilation. The method became largely redundant with the growth in use of explosives.

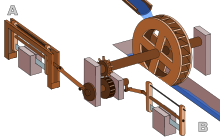

Hushing is an ancient and historic mining method using a flood or torrent of water to reveal mineral veins. The method was applied in several ways, both in prospecting for ores, and for their exploitation. Mineral veins are often hidden below soil and sub-soil, which must be stripped away to discover the ore veins. A flood of water is very effective in moving soil as well as working the ore deposits when combined with other methods such as fire-setting.

Metals and metal working had been known to the people of modern Italy since the Bronze Age. By 53 BC, Rome had expanded to control an immense expanse of the Mediterranean. This included Italy and its islands, Spain, Macedonia, Africa, Asia Minor, Syria and Greece; by the end of the Emperor Trajan's reign, the Roman Empire had grown further to encompass parts of Britain, Egypt, all of modern Germany west of the Rhine, Dacia, Noricum, Judea, Armenia, Illyria, and Thrace. As the empire grew, so did its need for metals.

The mines of Laurion are ancient mines located in southern Attica between Thoricus and Cape Sounion, approximately 50 kilometers south of the center Athens, in Greece. The mines are best known for producing silver, but they were also a source of copper and lead. A number of remnants of these mines are still present in the region.