The Burke and Hare murders were a series of sixteen murders committed over a period of about ten months in 1828 in Edinburgh, Scotland. They were undertaken by William Burke and William Hare, who sold the corpses to Robert Knox for dissection at his anatomy lectures.

Crail is a former royal burgh, parish and community council area in the East Neuk of Fife, Scotland.

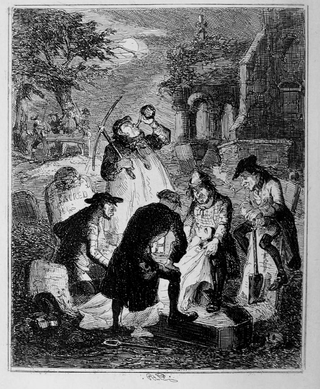

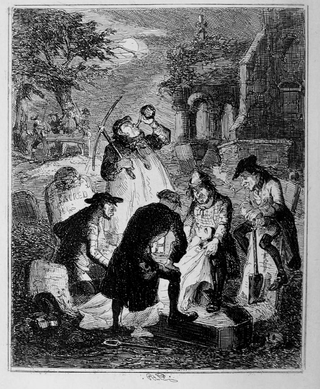

Body snatching is the illicit removal of corpses from graves, morgues, and other burial sites. Body snatching is distinct from the act of grave robbery as grave robbing does not explicitly involve the removal of the corpse, but rather theft from the burial site itself. The term 'body snatching' most commonly refers to the removal and sale of corpses primarily for the purpose of dissection or anatomy lectures in medical schools. The term was coined primarily in regard to cases in the United Kingdom and United States throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. However, there have been cases of body snatching in many countries, with the first recorded case dating back to 1319 in Bologna, Italy.

Grave robbery, tomb robbing, or tomb raiding is the act of uncovering a grave, tomb or crypt to steal commodities. It is usually perpetrated to take and profit from valuable artefacts or personal property. A related act is body snatching, a term denoting the contested or unlawful taking of a body, which can be extended to the unlawful taking of organs alone.

A lychgate or resurrection gate is a covered gateway found at the entrance to a traditional English or English-style churchyard. Examples also exist outside the British Isles in places such as Newfoundland, the Upland South and Texas in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Norway, and Sweden.

The Anatomy Act 1832 is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom that gave free licence to doctors, teachers of anatomy and bona fide medical students to dissect donated bodies. It was enacted in response to public revulsion at the illegal trade in corpses.

A mortsafe or mortcage was a construction designed to protect graves from disturbance and used in the United Kingdom. Resurrectionists had supplied schools of anatomy since the early 18th century. This was due to the necessity for medical students to learn anatomy by attending dissections of human subjects, which was frustrated by the very limited allowance of dead bodies – for example the corpses of executed criminals – granted by the government, which controlled the supply.

Auchenharvie Castle is a ruined castle near Torranyard on the A 736 Glasgow to Irvine road. Burnhouse lies to the north and Irvine to the south. It lies in North Ayrshire, Scotland.

Luncarty is a village in Perth and Kinross, Scotland, approximately 4 miles north of Perth. It lies between the A9 to the west, and the River Tay to the east.

Redgorton is a settlement in Gowrie, Perth and Kinross, Scotland. It lies a few miles from the River Tay and the A9 road, across the latter from Luncarty. It lies close to the Inveralmond Industrial Estate.

Marykirk is a village in the Kincardine and Mearns area of Aberdeenshire, Scotland, next to the border with Angus at the River North Esk.

Geoff Holder is a British author. He has written twenty non-fiction books on the paranormal, as well as on unusual and unexplained events and objects. His works include The Jacobites and the Supernatural and 101 Things to Do with a Stone Circle, Scottish Bodysnatchers and nine titles in The Guide to the Mysterious... series, covering subjects throughout Britain.

Torranyard is a small village or hamlet in North Ayrshire, Parish of Kilwinning, Scotland. It lies between the settlements of Auchentiber and Irvine on the A736 Lochlibo Road.

Resurrectionists were body snatchers who were commonly employed by anatomists in the United Kingdom during the 18th and 19th centuries to exhume the bodies of the recently dead. Between 1506 and 1752 only a very few cadavers were available each year for anatomical research. The supply was increased when, in an attempt to intensify the deterrent effect of the death penalty, Parliament passed the Murder Act 1752. By allowing judges to substitute the public display of executed criminals with dissection, the new law significantly increased the number of bodies anatomists could legally access. This proved insufficient to meet the needs of the hospitals and teaching centres that opened during the 18th century. Corpses and their component parts became a commodity, but although the practice of disinterment was hated by the general public, bodies were not legally anyone's property. The resurrectionists therefore operated in a legal grey area.

Udny Parish Church, now in private ownership, was a congregation of the Church of Scotland at Udny Green, Aberdeenshire in the north-east of Scotland, some 15 miles north of Aberdeen. Formerly known as Christ's Kirk, it was designed by the City of Aberdeen architect John Smith in 1821. Sited on the north edge of the village green, it is within the ancient Udny Parish and the Formartine committee area. It is a Category B listed building.

Udny Mort House is a morthouse in the old kirkyard at Udny Green, Aberdeenshire, north-east Scotland. Built in 1832, it is today a Category B listed building. It housed corpses until they started to decompose, so their graves would not be desecrated by resurrectionists and body-snatchers digging them up to sell the cadavers to medical colleges for dissection. Bodies were permitted to be stored for up to three months before burial. The circular morthouse was designed with a revolving platform and double doors. After the passage into law of the Anatomy Act 1832 Udny Mort House gradually fell into disuse; minutes of the committee responsible for its operation cease in about July 1836.

The Monkton Windmill, or Monkton Dovecote, was originally an early 18th century vaulted tower windmill located on the outskirts of the village of Monkton on the site of an Iron Age hillfort in South Ayrshire, Scotland. It was later converted into a dovecote and stood on the lands of the old Orangefield Estate.

Craigie is a small village and parish of 6,579 acres in the old district of Kyle, now South Ayrshire, four miles south of Kilmarnock, Scotland. This is mainly a farming district, lacking in woodland, with a low population density, and only one village. In the 19th century, high quality lime was quarried here with at least three sites in use in 1832.

Crail Parish Church is an ancient church building in Crail, Fife, Scotland. It is Category A listed, its oldest part dating to the 12th century. The walls and gravestones of its kirkyard are also Category A listed.

Woodhill House is a large office development on Westburn Road in Aberdeen, Scotland. It was built as the headquarters of Grampian Regional Council in 1977 and then became the offices and meeting place of Aberdeenshire Council in 1996.