27 October

On 27 October, officers in Moscow who were ready to resist the Bolshevik uprising gathered in the Alexander Military School . They were headed by the Chief of Staff of the Moscow Military District, Colonel K. K. Dorofeev. The forces of the Provisional Government, who gathered at the school, were about 300 people (officers, cadets, and students). They took the approaches to the school from the Smolensk market (the end of the Arbat), the Povarskaya and Malaya Nikitskaya, advanced from the Nikitsky Gates to Tverskoy Boulevard and took the western side of Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street to the building of Moscow University and the Kremlin. The volunteer squad of the students was called the "White Guard" - this was the first time this term was used. [9] Colonel V. F. Rar organized the defense of the barracks of the 1st Cadet Corps in Lefortovo by the forces of the cadets of the senior classes. Sergei Prokopovich, the only minister of the Provisional Government who was still available, arrived in Moscow on 27 October to organize resistance against the Bolsheviks.

At 18:00, Ryabtsev and the Public Security Committee established by Moscow City duma, having received confirmation from the Stavka of the Supreme Commander on the desertion of troops at the front and information about the movement of troops under the leadership of Alexander Kerensky and Pyotr Krasnov to Petrograd, declared the city to be under martial law and presented OM Berzin and the Moscow Military-Revolutionary Committee with an ultimatum: to dissolve the Military Revolutionary Committee, surrender the Kremlin and disarm revolutionary-minded military units. Representatives of the Military Revolutionary Committee agreed to withdraw the 193rd Regiment, but demanded the abandonment of the 56th Regiment, which was also stationed in the Kremlin.

According to other sources, the forces of the 193rd Regiment left the Kremlin in the morning, and when the ultimatum arrived at about 19:00 demanding the abolition of the MRC and the withdrawal of all the remaining revolutionary units from the Kremlin, the representatives of the ICRC responded with a refusal. [10]

On the same day, the Junkers attacked a detachment of "Dvintsi" soldiers, who had tried to break through to the Moscow City Council. 45 of the 150 people present were killed or wounded. The Junkers also made a raid on the Dorogomilovskiy MRC, after which they took up positions on the Garden Ring from the Crimean Bridge to the Smolensk Market and entered the Boulevard Ring from the Myasnitskie and Sretensky Gates, seizing the post office, telegraph and telephone exchange. [10]

28 October and the capture of the Kremlin by the Junkers

On the morning of 28 October, Ryabtsev demanded that Berzin surrender the Kremlin, saying that the city is under their control. Not knowing the actual situation and having no connection with the Military Revolutionary Committee, Berzin decided to surrender the Kremlin. The commander of the Armored Company of the 6th School of Ensigns demanded that the soldiers of the 56th Regiment surrender their weapons. The soldiers began to disarm and two companies of Cadets entered the Kremlin. According to the official Soviet version, based on the stories of the surviving soldiers of the 56th Regiment, after the captives surrendered their weapons, they were shot from small arms and machine guns trying to flee. [11]

On the morning of the 28th at 7 o'clock. Comrade Berzin collected us and said: ‘Comrades, I received an ultimatum and went into meditation for 20 minutes. The whole city is controlled by the other side.’ Left alone, isolated from the city, and not knowing what is happening outside the walls of the Kremlin, we decided to surrender with Comrade Berzin. Stole the machine guns to the arsenal, opened the gates and went to the barracks. In less than 30 minutes, an order was issued to go into the yard of the Kremlin and line up. Knowing nothing, we did so and saw that our "guests" came to us-the company of the cadets, the same armored cars that we did not let into the Kremlin last night, and one three-inch gun. All were built up before us. We were ordered to settle in front of the district court. The Junkers surrounded us with rifles at the ready. Some of them occupied the barracks in the doors, in the windows, too. A machine gun crackled at us from the Troitsky Gate. We were in a panic. Who rushed around. Whoever wanted to go to the barracks, they were beaten by bayonets. Some of us rushed to the school ensigns, and the ensigns threw a bomb. We found ourselves surrounded in a noose. A groan, the cries of our comrades wounded ... In 8 minutes, the massacre was over.

According to another version, when the soldiers saw that only two companies of Junkers had entered, they made an attempt to regain possession of their weapons, but this attempt failed, and many soldiers were killed or injured by machine-gun fire. [12] According to the recollections of the Junkers involved in the Kremlin's seizure, the surrender of the Kremlin was a tactical move in which the soldiers of the 56th Regiment attempted to drive the Junker Companies into a trap, which resulted in mass slaughter:

On the Senate Square was the whole regiment, in front of which was thrown a heap of weapons which they were handing over. In the barracks, I found a handful of soldiers, and, to my surprise, a lot of undiscarded weapons ... Suddenly I heard shots; glancing out the window, I saw that the soldiers as if they had been knocked down, were falling, and there was some kind of confusion in the square; Because of this, [I] quit my occupation and with my people quickly ran to the square, but on the stairs, many soldiers ran towards us. It turns out that the plan for the 56th Regiment was as follows: letting a small number of Junkers into the Kremlin and, apparently, obeying them, at the signal to rush and destroy them; The soldiers who fled to meet us were supposed to pick up weapons in the barracks and attack the cadets. [...] When everything more or less calmed down, we went to the square; there were wounded and killed soldiers and a cadet [...] It turned out that when the 56th Regiment made up of mainly cadets, and the shots that were fired from the barracks or the Arsenal were fired into the cadets - this was the signal for the remaining in the barracks to begin shooting with retained rifles from the upper rooms into the cadets on the square, behind the pile of weapons. The soldiers we met on the stairs ran. In response, the cadets opened fire ... [13] [14]

In the official report of the chief of the Moscow Artillery Warehouse, Major-General Kaihorodov, it is written that the cadets opened fire from machine guns after "several shots" that were heard from "somewhere". [15] According to various estimates, as a result of the shooting, 50 to 300 soldiers were killed. According to Ratkovsky, "six cadets and about two hundred soldiers were killed and wounded". [16]

After the capture of the Kremlin by the junkers, the position of the Military Revolutionary Committee became extremely difficult, as it was cut off from the Red Guards in the outskirts of the city, and telephone communication with them was impossible, since the telephone station was occupied by the cadets. In addition, supporters of the Provisional Government gained access to weapons stored in the Central Arsenal in the Kremlin.

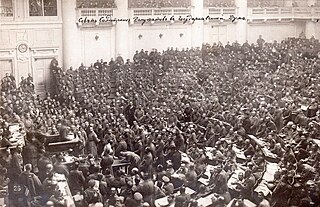

At the call of the MC of the RSDLP(b), the Military Revolutionary Committee and trade unions in the city, a general political strike began. The garrison meeting of regimental, company, command and brigade committees, which gathered in the Polytechnical Museum, offered all the military units they had to support the Military Revolutionary Committee, but decided to dissolve the previous leadership of the Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies and hold new elections, as a result of which a fighting body was established for contacts with the Military Revolutionary Committee. [10] By the end of 28 October, the revolutionary forces blockaded the center of the city. [10]

From 28 to 31 October, soldiers of the 193rd Infantry Regiment took part in the seizure of the Bryansk railway station, the Provision warehouses in battles at the Ostozhen positions, and stormed the headquarters of the Moscow Military District (7 Prechistenka Street). [17] During the assault, the company commander, Ensign A. A. Pomerantsev, was seriously wounded.