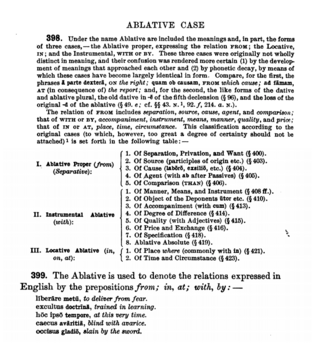

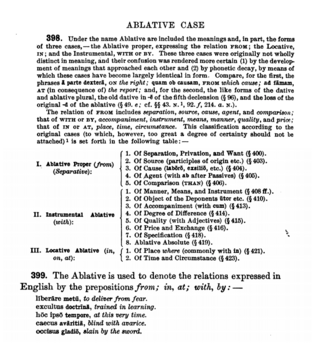

In grammar, the ablative case is a grammatical case for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives in the grammars of various languages; it is sometimes used to express motion away from something, among other uses. The word "ablative" derives from the Latin ablatus, the (suppletive) perfect, passive participle of auferre "to carry away".

A grammatical case is a category of nouns and noun modifiers that corresponds to one or more potential grammatical functions for a nominal group in a wording. In various languages, nominal groups consisting of a noun and its modifiers belong to one of a few such categories. For instance, in English, one says I see them and they see me: the nominative pronouns I/they represent the perceiver and the accusative pronouns me/them represent the phenomenon perceived. Here, nominative and accusative are cases, that is, categories of pronouns corresponding to the functions they have in representation.

Infinitive is a linguistics term for certain verb forms existing in many languages, most often used as non-finite verbs. As with many linguistic concepts, there is not a single definition applicable to all languages. The name is derived from Late Latin [modus] infinitivus, a derivative of infinitus meaning "unlimited".

A passive voice construction is a grammatical voice construction that is found in many languages. In a clause with passive voice, the grammatical subject expresses the theme or patient of the main verb – that is, the person or thing that undergoes the action or has its state changed. This contrasts with active voice, in which the subject has the agent role. For example, in the passive sentence "The tree was pulled down", the subject denotes the patient rather than the agent of the action. In contrast, the sentences "Someone pulled down the tree" and "The tree is down" are active sentences.

The Finnish language is spoken by the majority of the population in Finland and by ethnic Finns elsewhere. Unlike the Indo-European languages spoken in neighbouring countries, such as Swedish and Norwegian, which are North Germanic languages, or Russian, which is a Slavic language, Finnish is a Uralic language of the Finnic languages group. Typologically, Finnish is agglutinative. As in some other Uralic languages, Finnish has vowel harmony, and like other Finnic languages, it has consonant gradation.

In linguistics, a gerund is any of various nonfinite verb forms in various languages; most often, but not exclusively, it is one that functions as a noun. The name is derived from Late Latin gerundium, meaning "which is to be carried out". In English, the gerund has the properties of both verb and noun, such as being modifiable by an adverb and being able to take a direct object. The term "-ing form" is often used in English to refer to the gerund specifically. Traditional grammar makes a distinction within -ing forms between present participles and gerunds, a distinction that is not observed in such modern grammars as A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language and The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language.

Latin is a heavily inflected language with largely free word order. Nouns are inflected for number and case; pronouns and adjectives are inflected for number, case, and gender; and verbs are inflected for person, number, tense, aspect, voice, and mood. The inflections are often changes in the ending of a word, but can be more complicated, especially with verbs.

In linguistics, a participle is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, participle has been defined as "a word derived from a verb and used as an adjective, as in a laughing face".

Lithuanian grammar retains many archaic features from Proto-Balto-Slavic that have been lost in other Balto-Slavic languages.

In Latin grammar, a gerundive is a verb form that functions as a verbal adjective.

In English, the passive voice is marked by a subject that is followed by a stative verb complemented by a past participle. For example:

The enemy was defeated. Caesar was stabbed.

In Ancient Greek grammar, the genitive absolute is a grammatical construction consisting of a participle and often a noun both in the genitive case, which is very similar to the ablative absolute in Latin. A genitive absolute construction serves as a dependent clause, usually at the beginning of a sentence, in which the genitive noun is the subject of the dependent clause and the participle takes on the role of predicate.

Ancient Greek grammar is morphologically complex and preserves several features of Proto-Indo-European morphology. Nouns, adjectives, pronouns, articles, numerals and especially verbs are all highly inflected.

Standard Kannada grammar is primarily based on Keshiraja's Shabdamanidarpana which provides the fullest systematic exposition of Kannada language. The earlier grammatical works include portions of Kavirajamarga of 9th century, Kavyavalokana and Karnatakabhashabhushana both authored by Nagavarma II in first half of the 12th century.

In linguistic morphology, inflection is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and definiteness. The inflection of verbs is called conjugation, while the inflection of nouns, adjectives, adverbs, etc. can be called declension.

Ossetian, commonly referred to as Ossetic and rarely as Ossete, is an Eastern Iranian language that is spoken predominantly in Ossetia, a region situated on both sides of the Russian-Georgian border in the Greater Caucasus region. It is the native language of the Ossetian people, and a relative and possibly a descendant of the extinct Scythian, Sarmatian, and Alanic languages.

This article deals with the grammar of the Udmurt language.

In linguistics, an absolute construction is a grammatical construction standing apart from a normal or usual syntactical relation with other words or sentence elements. It can be a non-finite clause that is subordinate in form and modifies an entire sentence, an adjective or possessive pronoun standing alone without a modified substantive, or a transitive verb when its object is implied but not stated. The term absolute derives from Latin absolūtum, meaning "loosened from" or "separated".

This article concerns the morphology of the Albanian language, including the declension of nouns and adjectives, and the conjugation of verbs. It refers to the Tosk-based Albanian standard regulated by the Academy of Sciences of Albania.

Latin syntax is the part of Latin grammar that covers such matters as word order, the use of cases, tenses and moods, and the construction of simple and compound sentences, also known as periods.