The Cherokee are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern North Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, southwestern Virginia, edges of western South Carolina, northern Georgia and northeastern Alabama.

Pocahontas was a Native American woman belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of Powhatan, the paramount chief of a network of tributary tribes in the Tsenacommacah, encompassing the Tidewater region of what is today the U.S. state Virginia.

The Wampanoag, also rendered Wôpanâak, are a Native American people of the Northeastern Woodlands currently based in southeastern Massachusetts and formerly parts of eastern Rhode Island. Their historical territory includes the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket.

The Powhatan people (;) are Native Americans who belong to member tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, or Tsenacommacah. They are Algonquian peoples whose historic territories were in eastern Virginia.

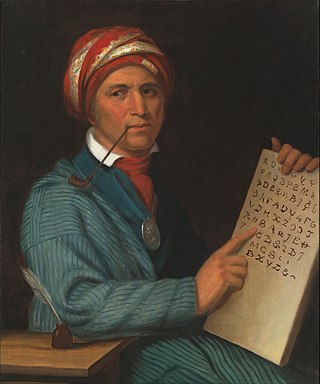

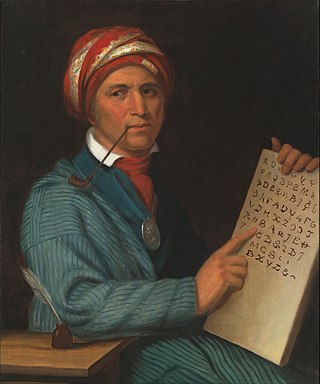

Nanyehi, known in English as Nancy Ward, was a Beloved Woman and political leader of the Cherokee. She advocated for peaceful coexistence with European Americans and, late in life, spoke out for Cherokee retention of tribal hunting lands. She is credited with the introduction of dairy products to the Cherokee economy.

The Tuscarora War was fought in North Carolina from September 10, 1711, until February 11, 1715, between the Tuscarora people and their allies on one side and European American settlers, the Yamasee, and other allies on the other. This was considered the bloodiest colonial war in North Carolina. The Tuscarora signed a treaty with colonial officials in 1718 and settled on a reserved tract of land in Bertie County, North Carolina. The war incited further conflict on the part of the Tuscarora and led to changes in the slave trade of North and South Carolina.

Powhatan, whose proper name was Wahunsenacawh, was the leader of the Powhatan, an alliance of Algonquian-speaking Native Americans living in Tsenacommacah, in the Tidewater region of Virginia at the time when English settlers landed at Jamestown in 1607.

Weetamoo, also referred to as Weethao, Weetamoe, Wattimore, Namumpum, and Tatapanunum, was a Pocasset Wampanoag Native American Chief. She was the sunksqua, or female sachem, of Pocasset tribe, which occupied contemporary Tiverton, Rhode Island in 1620. The Pocasset, which she led, was one of groups of the Wampanoag.

Black Indians are Native American people – defined as Native American due to being affiliated with Native American communities and being culturally Native American – who also have significant African American heritage.

The Native American tribes in Virginia are the Indigenous peoples whose tribal nations historically or currently are based in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States of America.

The Texas–Indian wars were a series of conflicts between settlers in Texas and the Southern Plains Indians during the 19th-century. Conflict between the Plains Indians and the Spanish began before other European and Anglo-American settlers were encouraged—first by Spain and then by the newly Independent Mexican government—to colonize Texas in order to provide a protective-settlement buffer in Texas between the Plains Indians and the rest of Mexico. As a consequence, conflict between Anglo-American settlers and Plains Indians occurred during the Texas colonial period as part of Mexico. The conflicts continued after Texas secured its independence from Mexico in 1836 and did not end until 30 years after Texas became a state of the United States, when in 1875 the last free band of Plains Indians, the Comanches led by Quahadi warrior Quanah Parker, surrendered and moved to the Fort Sill reservation in Oklahoma.

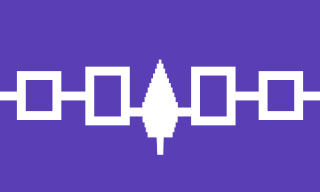

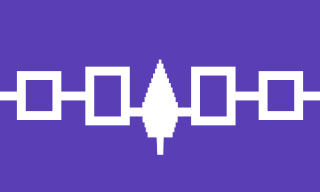

The Iroquois, also known as the Five Nations or the Six Nations and by the endonym Haudenosaunee, are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of Native Americans and First Nations peoples in northeast North America and Upstate New York. They were known during the colonial years to the French as the "Iroquois League", and later as the "Iroquois Confederacy". The English called them the "Five Nations", including the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca. After 1722, the Iroquoian-speaking Tuscarora from the southeast were accepted into the confederacy, which became known as the Six Nations.

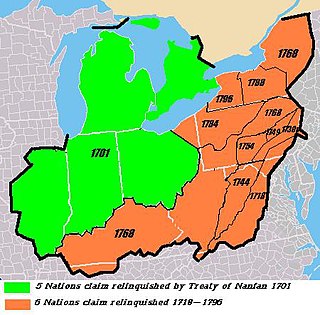

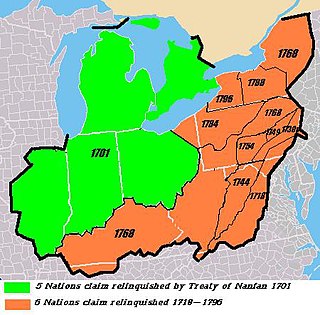

The Six Nations land cessions were a series of land cessions by the Haudenosaunee and Lenape which ceded large amounts of land, including both recently conquered territories acquired from other indigenous peoples in the Beaver Wars, and ancestral lands to the Thirteen Colonies and the United States. The land ceded covered, partially or in the entire, the U.S. states of New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Tennessee and North Carolina. They were bordered to the west by the Algonquian lands in the Ohio Country, Cherokee lands to the south, and Muscogee and Choctaw lands to the southeast.

Slavery among Native Americans in the United States includes slavery by and enslavement of Native Americans roughly within what is currently the United States of America.

During and after the European colonization of the Americas, European settlers practiced widespread enslavement of Indigenous peoples. In the 15th Century, the Spanish introduced chattel slavery through warfare and the cooption of existing systems. A number of other European powers followed suit, and from the 15th through the 19th centuries, between two and five million Indigenous people were enslaved, which had a devastating impact on many Indigenous societies, contributing to the overwhelming population decline of Indigenous peoples in the Americas.

The Indian princess is usually a stereotypical and inaccurate representation of a Native American or other Indigenous woman of the Americas. The term "princess" was often mistakenly applied to the daughters of tribal chiefs or other community leaders by early American colonists who mistakenly believed that Indigenous people shared the European system of royalty. This inaccurate portrayal has continued in popular animation, with characters that conform to European standards of beauty, with the most famous misrepresentation being that of Pocahontas. Frequently, the "Indian Princess" stereotype is paired with the "Pocahontas theme" in which the princess "offers herself to a captive Christian knight, a prisoner of her father, and after rescuing him, she is converted to Christianity and lives with him in his native land." - a false narrative that did not even happen quite that way to the real child who inspired the Pocahontas stories. The phrase "Indian princess", when used in this way, is often considered to be a derogatory term, a type of racial slur, and is deemed offensive by Native Americans.

Opossunoquonuske, was a Weroansqua of an Appomattoc town near the mouth of the Appomattox River. Weroansqua is an Algonquian word meaning leader or commander among the Powhatan confederacy of Virginia coast and Chesapeake Bay region. She was known as the queen of Appamatuck, The community she led was large enough to provide an estimated twenty warriors to the Powhatan Confederacy.

Native American slave ownership refers to the ownership of enslaved Africans by Native Americans from the colonial period to the American Civil War. Waves of European colonization brought enslaved Africans to North America. Following this development many indigenous tribes began to acquire Africans as slaves. Many prominent people from the "Five Civilized Tribes" purchased slaves from their white neighbors and became members of the planter class.

In May 1607, one hundred men and young boys were on an expedition where they arrived in what is now known as Virginia. This group were the first permanent English settlers in America. They named the colony of Jamestown, after the English King James. The site was chosen precisely for its location and beneficial factors. Jamestown was surrounded by water on three sides of the land; this made it easily accessible for ships to come and go. It was far enough inland, making it easier to defend from a possible Spanish attack. At the time, it was said that the men had to be able to create a living before any women could be a part of the colony.