Ögedei was the third son of Genghis Khan and second Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, succeeding his father. He continued the expansion of the empire that his father had begun, and was a world figure when the Mongol Empire reached its farthest extent west and south during the Mongol invasions of Europe and East Asia. Like all of Genghis' primary sons, he participated extensively in conquests in China, Iran, and Central Asia.

Möngke was the fourth khagan of the Mongol Empire, ruling from July 1, 1251, to August 11, 1259. He was the first Khagan from the Toluid line, and made significant reforms to improve the administration of the Empire during his reign. Under Möngke, the Mongols conquered Iraq and Syria as well as the kingdom of Dali.

The Chagatai Khanate was a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate that comprised the lands ruled by Chagatai Khan, second son of Genghis Khan, and his descendants and successors. Initially it was a part of the Mongol Empire, but it became a functionally separate khanate with the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire after 1259. The Chagatai Khanate recognized the nominal supremacy of the Yuan dynasty in 1304, but became split into two parts in the mid-14th century: the Western Chagatai Khanate and the Moghulistan Khanate.

Temür Öljeytü Khan, born Temür, also known by the temple name Chengzong was the second emperor of the Yuan dynasty, ruling from May 10, 1294 to February 10, 1307. Apart from Emperor of China, he is considered as the sixth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire or Mongols, although it was only nominal due to the division of the empire. He was an able ruler of the Yuan, and his reign established the patterns of power for the next few decades. His name means "blessed iron Khan" in the Mongolian language.

Kadan was the son of the second Great Khan of the Mongols Ögedei and a concubine. He was the grandson of Genghis Khan and the brother of Güyük Khan. During the Mongol invasion of Europe, Kadan, along with Baidar and Orda Khan, led the Mongol diversionary force that attacked Poland, while the main Mongol force struck the Kingdom of Hungary.

Mengu-Timur or Möngke Temür (?–1280), son of Toqoqan Khan and Buka Ujin of Oirat and the grandson of Batu Khan. He was a khan of the Golden Horde, a division of the Mongol Empire in 1266–1280. His name literally means "Eternal Iron" in the Mongolian language.

In modern times the Mongols are primarily Tibetan Buddhists, but in previous eras, especially during the time of the Mongol empire, they were primarily shamanist, and had a substantial minority of Christians, many of whom were in positions of considerable power. Overall, Mongols were highly tolerant of most religions, and typically sponsored several at the same time. Many Mongols had been proselytized by the Church of the East since about the seventh century, and some tribes' primary religion was Nestorian. In the time of Genghis Khan, his sons took Christian wives of the Keraites, and under the rule of Genghis Khan's grandson, Möngke Khan, the primary religious influence was Christian.

Aju (1227–1287) was a general and chancellor of the Mongol Empire and the Yuan Dynasty. He was from the Jarchud clan of the Mongol Uriankhai. His grandfather was Subutai, the honored general and Noyan of Genghis Khan; his father was Uryankhadai.

Kublai was the fifth Khagan of the Mongol Empire, reigning from 1260 to 1294. He also founded the Yuan dynasty in China as a conquest dynasty in 1271, and ruled as the first Yuan emperor until his death in 1294.

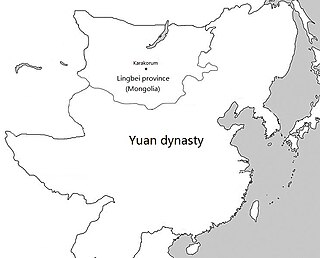

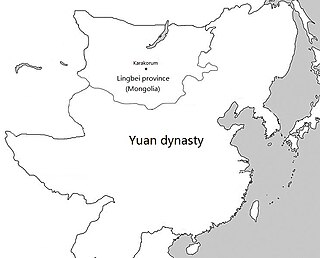

The Yuan dynasty was the ruling dynasty of China and Mongolia established by Kublai Khan and a khanate of the Mongol Empire.

The House of Ögedei, sometimes called the Ögedeids, were an influential family of Mongol Borjigin from the 12th to 14th centuries. They were descended from Ögedei Khan (c.1186-1241), a son of Genghis Khan who had become his father's successor, second Khagan of the Mongol Empire. Ögedei continued the expansion of the Mongol Empire.

According to Rashid-al-Din Hamadani (1247–1318), Genghis Khan's eldest son, Jochi, had nearly 40 sons, of whom he names 14. When he died, they inherited their father's dominions as fiefs under the rule of their brothers, Batu Khan, as supreme khan and Orda Khan, who, although the elder of the two, agreed that Batu enjoyed primacy as the Khan of the Golden Horde.

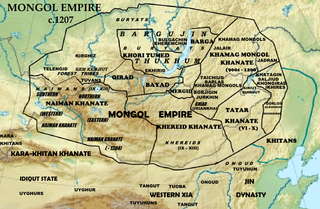

The division of the Mongol Empire began when Möngke Khan died in 1259 in the siege of Diaoyu castle with no declared successor, precipitating infighting between members of the Tolui family line for the title of Great Khan that escalated to the Toluid Civil War. This civil war, along with the Berke–Hulagu war and the subsequent Kaidu–Kublai war greatly weakened the authority of the Great Khan over the entirety of the Mongol Empire and the empire fractured into autonomous khanates, including the Golden Horde in the northwest, the Chagatai Khanate in the middle, the Ilkhanate in the southwest, and the Yuan dynasty in the east based in modern-day Beijing, although the Yuan emperors held the nominal title of Khagan of the empire. The four khanates each pursued their own separate interests and objectives, and fell at different times.

The Yuan dynasty in Inner Asia was the domination of the Yuan dynasty in Inner Asia in the 13th and the 14th centuries. The Genghisid rulers of the Yuan came from the Mongolian steppe, and the Mongols under Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) based in Khanbaliq, a Chinese-style dynasty that incorporated many aspects of Mongolian and Inner Asian political and military institutions. Actual Yuan rule extended to Manchuria, Mongolia, the Tibetan Plateau and parts of Xinjiang. People from these Inner Asian regions other than the Mongols usually belonged to the Semu class. In addition, the Yuan emperors held nominal suzerainty over the three western Mongol khanates, but they were essentially autonomous and ruled separately due to the division of the Mongol Empire since the Toluid Civil War in the 1260s.

The Kaidu–Kublai war was a war between Kaidu, the leader of the House of Ögedei and the de facto khan of the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia, and Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan dynasty in China and his successor Temür Khan that lasted a few decades from 1268 to 1301. It followed the Toluid Civil War (1260–1264) and resulted in the permanent division of the Mongol Empire. By the time of Kublai's death in 1294, the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate khanates or empires: the Golden Horde khanate in the northwest, the Chagatai Khanate in the middle, the Ilkhanate in the southwest, and the Yuan dynasty in the east based in modern-day Beijing. Although Temür Khan later made peace with the three western khanates in 1304 after Kaidu's death, the four khanates continued their own separate development and fell at different times.

Manchuria under Yuan rule refers to the Yuan dynasty's rule over Manchuria, including modern Northeast China and Outer Manchuria from the beginning to the end of the dynasty. Mongol rule over Manchuria was established during the Mongol Empire's conquest of the Jurchen Jin dynasty in the early 13th century. It became a part of the Yuan dynasty, division of the Mongol Empire, when the dynasty was founded by the Mongol leader Kublai Khan. Even after the overthrown of the Mongol Yuan dynasty by the Ming dynasty founded by native Chinese in 1368, Manchuria was still controlled by the Northern Yuan dynasty based in Mongolia for almost 20 years, until it was conquered by the Ming during the Ming military campaign against Naghachu and put under Ming rule.

The Yuan dynasty ruled over the Mongolian steppe, including both Inner and Outer Mongolia as well as part of southern Siberia, for roughly a century between 1271 and 1368. The Mongolian Plateau is where the ruling Mongols of the Yuan dynasty as founded by Kublai Khan came from, thus it enjoyed a somewhat special status during the Mongol Yuan dynasty, division of the Mongol Empire, although the capital of the dynasty had been moved from Karakorum to Khanbaliq since the beginning of Kublai Khan's reign, and Mongolia had been turned into a province by the early 14th century.