Impi is a Nguni word meaning war or combat and by association any body of men gathered for war, for example impi ya masosha is a term denoting an army. Impi were formed from regiments from large militarised homesteads. In English impi is often used to refer to a Zulu regiment, which is called an ibutho in Zulu, or the army of the Zulu Kingdom.

Shaka kaSenzangakhona, also known as Shaka Zulu and Sigidi kaSenzangakhona, was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1816 to 1828. One of the most influential monarchs of the Zulu, he ordered wide-reaching reforms that reorganized the military into a formidable force.

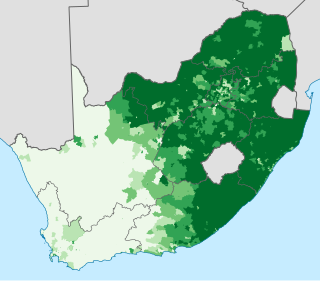

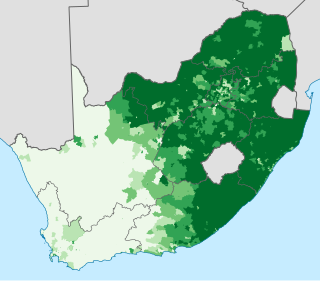

Zulu people are a native people of Southern Africa of the Nguni. The Zulu people are the largest ethnic group and nation in South Africa, living mainly in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Nguni stick-fighting is a martial art traditionally practiced by teenage Nguni herdboys in South Africa. Each combatant is armed with two long sticks, one of which is used for defense and the other for offense. Little armor is used. For up to five hours, players alternate between offense and defense to score points based on which body part is struck.

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in present-day South Africa from January to early July 1879 between forces of the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. Two famous battles of the war were the Zulu victory at Isandlwana and the British defence at Rorke's Drift.

Mpande kaSenzangakhona was monarch of the Zulu Kingdom from 1840 to 1872. He was a half-brother of Sigujana, Shaka and Dingane, who preceded him as Zulu kings. He came to power after he had overthrown Dingane in 1840.

Cetshwayo kaMpande was the king of the Zulu Kingdom from 1873 to 1884 and its Commander in Chief during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. His name has been transliterated as Cetawayo, Cetewayo, Cetywajo and Ketchwayo. Cetshwayo consistently opposed the war and sought fruitlessly to make peace with the British and was defeated and exiled following the Zulu defeat in the war. He was later allowed to return to Zululand, where he died in 1884.

The Ndwandwe–Zulu War of 1817–1819 was a war fought between the expanding Zulu Kingdom and the Ndwandwe tribe in South Africa.

The Battle of Gqokli Hill has been claimed by some to have occurred on or around April 1818, a part of the Ndwandwe-Zulu War between Shaka of the Zulu nation and Zwide of the Ndwandwe just south of present-day Ulundi. However, some claim that the battle never actually happened.

Lobengula Khumalo was the second and last official king of the Northern Ndebele people. Both names in the Ndebele language mean "the men of the long shields", a reference to the Ndebele warriors' use of the Nguni shield.

Ndlela kaSompisi was a key general to Zulu Kings Shaka and Dingane. He rose to prominence as a highly effective warrior under Shaka. Dingane appointed him as his inDuna, or chief advisor. He was also the principal commander of Dingane's armies. However, Ndlela's failure to defeat the Boers under Andries Pretorius and a rebellion against Dingane led to his execution. This made him a failure in the eyes of his people.

An assegai or assagai is a polearm used for throwing, usually a light spear or javelin made up of a wooden handle with an iron tip.

Blacks are the majority ethno-racial group in South Africa, belonging to various Bantu ethnic groups. They are descendants of Southern Bantu-speaking peoples who settled in South Africa during the Bantu expansion.

The Zulu royal family, also known as the House of Zulu consists of the King of the Zulu Nation, his consorts, and all of his legitimate descendants. The legitimate descendants of all previous kings are also sometimes considered to be members.

Sigananda kaZokufa was a Zulu aristocrat whose life spanned the reigns of four Zulu kings in southeastern Africa. According to oral history, Sigananda's grandfather was chief Mvakela, who married a sister of Nandi, King Shaka's mother, and that his father was Inkosi Zokufa. He also said he had a son called Ndabaningi.

The Nguni people are a linguistic cultural group of Bantu cattle herders who migrated from central Africa into Southern Africa, made up of ethnic groups formed from iron age and proto-agrarians, with offshoots in neighboring colonially-created countries in Southern Africa. Swazi people live in both South Africa and Eswatini, while Ndebele people live in both South Africa and Zimbabwe.

The Bhaca people, or amaBhaca, are an Nguni ethnic group in South Africa.

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire, was a monarchy in Southern Africa. During the 1810s, Shaka established a standing army that consolidated rival clans and built a large following which ruled a wide expanse of Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to the Pongola River in the north.

The Battle of Ndondakusuka, often known as the Second Zulu Civil War, fought on 2 December 1856, was the culmination of a succession struggle in the Zulu Kingdom between Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi, the two eldest sons of the king Mpande. Mbuyazi was defeated at the battle and was killed, leaving Cetshwayo in de facto control of the kingdom, though his father remained king. Mbuyazi's followers, including five other sons of King Mpande, were massacred in the aftermath of the battle.

Matiwane ka Masumpa, son of Masumpa, was the king of an independent Nguni-speaking nation, the amaNgwane, a people named after Matiwane's ancestor Ngwane ka Kgwadi. The amaNgwane lived at the headwaters of the White Umfolozi, in what is now Vryheid in northern KwaZulu-Natal. The cunning of Matiwane would keep the amaNgwane one step ahead of the ravages of the rising Zulu kingdom, but their actions also set the Mfecane in motion. After his nation was ousted from their homeland by Zwide with Shaka, Matiwane and his armies clashed with neighboring nations as he attempted to nourish his people. Eventually he fled South into lands occupied by abaThembu, amaMpondo and the neighboring Xhosa nations, which ultimately teamed up with the British and got his nation dismantled and scattered as smaller splinters at the Battle of Mbholompo in what is today Mthatha in the Eastern Cape. In his exodus from Mthatha, Matiwane and the biggest of the amaNgwane splinters was sheltered by baSotho but eventually had to return to his country, Ntenjwa, which he had settled briefly upon fleeing from his old country on uMfolozi omhlophe. Being back at Ntenjwa put a very much weakened amaNgwane and the king, Matiwane, within easy reach of the Zulu nation he had fled from. Matiwane had to then go make peace with the Zulu king, now Dingane, successor to Shaka. This despotic ruler put Matiwane to death shortly after Matiwane sought peace with the amaZulu.