Existence is the state of having being or reality in contrast to nonexistence and nonbeing. Existence is often contrasted with essence: the essence of an entity is its essential features or qualities, which can be understood even if one does not know whether the entity exists.

Intentionality is the mental ability to refer to or represent something. Sometimes regarded as the mark of the mental, it is found in mental states like perceptions, beliefs or desires. For example, the perception of a tree has intentionality because it represents a tree to the perceiver. A central issue for theories of intentionality has been the problem of intentional inexistence: to determine the ontological status of the entities which are the objects of intentional states.

In metaphysics and the philosophy of language, an empty name is a proper name that has no referent.

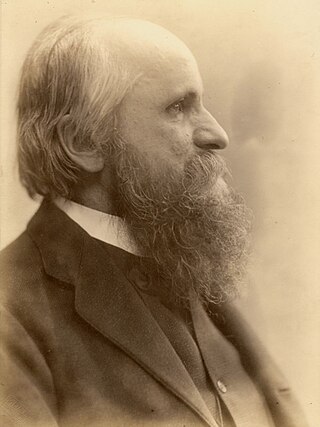

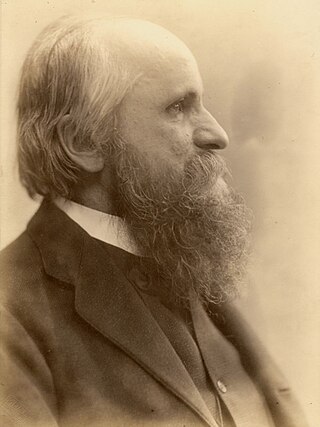

Alexius Meinong Ritter von Handschuchsheim was an Austrian philosopher, a realist known for his unique ontology and theory of objects. He also made contributions to philosophy of mind and theory of value.

Richard Sylvan was a New Zealand–born philosopher, logician, and environmentalist.

In logic and philosophy, a property is a characteristic of an object; for example, a red object is said to have the property of redness. The property may be considered a form of object in its own right, able to possess other properties. A property, however, differs from individual objects in that it may be instantiated, and often in more than one object. It differs from the logical and mathematical concept of class by not having any concept of extensionality, and from the philosophical concept of class in that a property is considered to be distinct from the objects which possess it. Understanding how different individual entities can in some sense have some of the same properties is the basis of the problem of universals.

In philosophy and the arts, a fundamental distinction is between things that are abstract and things that are concrete. While there is no general consensus as to how to precisely define the two, examples include that things like numbers, sets, and ideas are abstract objects, while plants, dogs, and planets are concrete objects. Popular suggestions for a definition include that the distinction between concreteness versus abstractness is, respectively: between (1) existence inside versus outside space-time; (2) having causes and effects versus not; 3) being related, in metaphysics, to particulars versus universals; and (4) belonging to either the physical versus the mental realm. Another view is that it is the distinction between contingent existence versus necessary existence; however, philosophers differ on which type of existence here defines abstractness, as opposed to concreteness. Despite this diversity of views, there is broad agreement concerning most objects as to whether they are abstract or concrete, such that most interpretations agree, for example, that rocks are concrete objects while numbers are abstract objects.

The Graz School, also Meinong's School, of experimental psychology and object theory was headed by Alexius Meinong, who was professor and Chair of Philosophy at the University of Graz where he founded the Graz Psychological Institute in 1894. The Graz School's phenomenological psychology and philosophical semantics achieved important advances in philosophy and psychological science.

In analytic philosophy, actualism is the view that everything there is is actual. Another phrasing of the thesis is that the domain of unrestricted quantification ranges over all and only actual existents.

Philosophical realism—usually not treated as a position of its own but as a stance towards other subject matters— is the view that a certain kind of thing has mind-independent existence, i.e. that it exists even in the absence of any mind perceiving it or that its existence is not just a mere appearance in the eye of the beholder. This includes a number of positions within epistemology and metaphysics which express that a given thing instead exists independently of knowledge, thought, or understanding. This can apply to items such as the physical world, the past and future, other minds, and the self, though may also apply less directly to things such as universals, mathematical truths, moral truths, and thought itself. However, realism may also include various positions which instead reject metaphysical treatments of reality altogether.

A free logic is a logic with fewer existential presuppositions than classical logic. Free logics may allow for terms that do not denote any object. Free logics may also allow models that have an empty domain. A free logic with the latter property is an inclusive logic.

Ernst Mally was an Austrian analytic philosopher, initially affiliated with Alexius Meinong's Graz School of object theory. Mally was one of the founders of deontic logic and is mainly known for his contributions in that field of research. In metaphysics, he is known for introducing a distinction between two kinds of predication, better known as the dual predication approach.

Edward Nouri Zalta is an American philosopher who is a senior research scholar at the Center for the Study of Language and Information at Stanford University. He received his BA from Rice University in 1975 and his PhD from the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 1981, both in philosophy. Zalta has taught courses at Stanford University, Rice University, the University of Salzburg, and the University of Auckland. Zalta is also the Principal Editor of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Terence Dwight Parsons (1939–2022) was an American philosopher, specializing in philosophy of language and metaphysics. He was emeritus professor of philosophy at UCLA.

Noneism, also known as modal Meinongianism, is both a philosophical and theological theory. In a philosophical and metaphysical context, the theory suggests that some things do not exist. That definition was first conceptualized by Richard Sylvan in 1980 and then later expanded on by Graham Priest in 2005. In a theological context, noneism is the practice of spirituality without an affiliation to organized religion.

Héctor-Neri Castañeda was a Guatemalan-American philosopher and founder of the journal Noûs.

William Joseph Rapaport is a North American philosopher who is an associate professor emeritus of the University at Buffalo.

In metaphysics, Plato's beard is a paradoxical argument dubbed by Willard Van Orman Quine in his 1948 paper "On What There Is". The phrase came to be identified as the philosophy of understanding something based on what does not exist.

Abstract object theory (AOT) is a branch of metaphysics regarding abstract objects. Originally devised by metaphysician Edward Zalta in 1981, the theory was an expansion of mathematical Platonism.

The Meinongian argument is a type of ontological argument or an "a priori argument" that seeks to prove the existence of God. This is through an assertion that there is "a distinction between different categories of existence." The premise of the ontological argument is based on Alexius Meinong's works. Some scholars also associate it with St. Anselm's ontological argument.