Tawi-Tawi, officially the Province of Tawi-Tawi, is an island province in the Philippines located in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). The capital of Tawi-Tawi is Bongao.

Lanao del Sur, officially the Province of Lanao del Sur, is a province in the Philippines located in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). The capital is the city of Marawi, and it borders Lanao del Norte to the north, Bukidnon to the east, and Maguindanao del Norte and Cotabato to the south. To the southwest lies Illana Bay, an arm of the Moro Gulf.

The Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao was an autonomous region of the Philippines, located in the Mindanao island group of the Philippines, that consisted of five predominantly Muslim provinces: Basilan, Lanao del Sur, Maguindanao, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi. It was the only region that had its own government. The region's de facto seat of government was Cotabato City, although this self-governing city was outside its jurisdiction.

Kulintang is a modern term for an ancient instrumental form of music composed on a row of small, horizontally laid gongs that function melodically, accompanied by larger, suspended gongs and drums. As part of the larger gong-chime culture of Southeast Asia, kulintang music ensembles have been playing for many centuries in regions of the Southern Philippines, Eastern Malaysia, Eastern Indonesia, Brunei and Timor, Kulintang evolved from a simple native signaling tradition, and developed into its present form with the incorporation of knobbed gongs from Sundanese people in Java Island, Indonesia. Its importance stems from its association with the indigenous cultures that inhabited these islands prior to the influences of Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity or the West, making kulintang the most developed tradition of Southeast Asian archaic gong-chime ensembles.

The Tausūg, are an ethnic group of the Philippines and Malaysia. A small population can also be found in the northern part of North Kalimantan, Indonesia. The Tausūg are part of the wider political identity of Muslim Filipinos of western Mindanao, the Sulu archipelago, and southern Palawan, collectively referred to as the Moro people. The Tausugs originally had an independent state known as the Sultanate of Sulu, which once exercised sovereignty over the present day provinces of Basilan, Palawan, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi, Zamboanga City, eastern part of Sabah and eastern part of North Kalimantan. They are also known in the Malay language as Suluk.

The Maranao people, also spelled Meranao, Maranaw, and Mëranaw, is a predominantly Muslim Filipino ethnic group native to the region around Lanao Lake in the island of Mindanao. They are known for their artwork, weaving, wood, plastic and metal crafts and epic literature, the Darangen. They are ethnically and culturally closely related to the Iranun, and Maguindanaon, all three groups being denoted as speaking Danao languages and giving name to the island of Mindanao. They are grouped with other Moro people due to their shared religion.

The malong is a traditional Filipino-Bangsamoro rectangular or tube-like wraparound skirt bearing a variety of geometric or okir designs. The malong is traditionally used as a garment by both men and women of the numerous ethnic groups in the mainland Mindanao and parts of the Sulu Archipelago. They are wrapped around at waist or chest-height and secured by tucked ends, with belts of braided material or other pieces of cloth, or are knotted over one shoulder. They were traditionally hand-woven, with the patterns usually distinctive to a particular ethnic group. However, modern malong are usually machine-made or even imported, with patterns that mimic the traditional local designs.

Tugaya, officially the Municipality of Tugaya, is a 5th class municipality in the province of Lanao del Sur, Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a population of 24,778 people.

The Iranun are an Austronesian ethnic group native to southwestern Mindanao, Philippines. They are ethnically and culturally closely related to the Maranao, and Maguindanaon, all three groups being denoted as speaking Danao languages and giving name to the island of Mindanao. The Iranun were traditionally sailors and were renowned for their ship-building skills. Iranun communities can also be found in Malaysia and Philippines.

The Sama-Bajau include several Austronesian ethnic groups of Maritime Southeast Asia. The name collectively refers to related people who usually call themselves the Sama or Samah ; or are known by the exonym Bajau. They usually live a seaborne lifestyle and use small wooden sailing vessels such as the perahu, djenging (balutu), lepa, and vinta (pilang). Some Sama-Bajau groups native to Sabah are also known for their traditional horse culture.

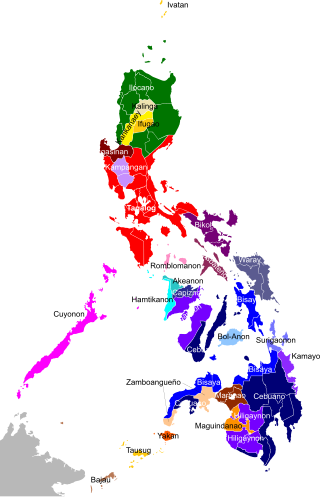

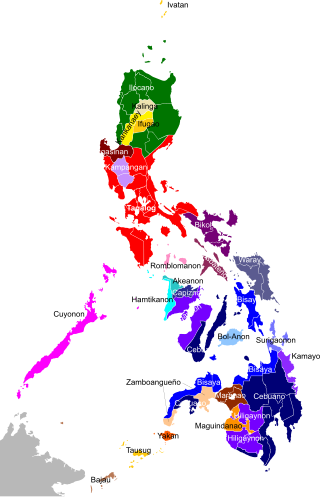

The Philippines is inhabited by more than 182 ethnolinguistic groups, many of which are classified as "Indigenous Peoples" under the country's Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997. Traditionally-Muslim peoples from the southernmost island group of Mindanao are usually categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are classified as Indigenous peoples or not. About 142 are classified as non-Muslim Indigenous people groups, and about 19 ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither Indigenous nor Moro. Various migrant groups have also had a significant presence throughout the country's history.

The vinta is a traditional outrigger boat from the Philippine island of Mindanao. The boats are made by Sama-Bajau, Tausug and Yakan peoples living in the Sulu Archipelago, Zamboanga peninsula, and southern Mindanao. Vinta are characterized by their colorful rectangular lug sails (bukay) and bifurcated prows and sterns, which resemble the gaping mouth of a crocodile. Vinta are used as fishing vessels, cargo ships, and houseboats. Smaller undecorated versions of the vinta used for fishing are known as tondaan.

Pangalay is the traditional "fingernail" dance of the Tausūg people of the Sulu Archipelago and eastern coast Bajau of Sabah.

The Culture of Basilan are derived from the three main cultural ethnolinguistic nations, the Yakan, Suluanon Tausug and the Zamboangueño in the southern Philippines. Both Yakans and Tausugs are predominantly Muslim, joined by their kin from the Sama, Badjao, Maranao, and other Muslim ethnolinguistic groups of Mindanao, while the Zamboangueños are primarily Christian, joined by the predominantly Christian ethnolinguistic groups; the Cebuano, Ilocano, Tagalog and others. These three main groups, however, represent Basilan's tri-people or tri-ethnic group community.

A torogan is a traditional ancestral house built by the Maranao people of Lanao, Mindanao, Philippines for the nobility. A torogan was a symbol of high social status. Such a residence was once a home to a sultan or datu in the Maranao community. Nowadays, concrete houses are found all over Maranaw communities, but there remain torogans a hundred years old. The best-known are in Dayawan and Marawi City, and around Lake Lanao.

The Kawayan Torogan (also Torogan sa Kawayan)is a traditional Maranao torogan (house) built by Sultan sa Kawayan Makaantal in Bubung Malanding, Marantao, Lanao del Sur. Being the last standing example of the house of the elite members of the Maranao tribe, and the only remaining habitable torogan, it was declared as a National Cultural Treasure by the National Museum of the Philippines in 2008. The location of the structure is in Marawi City according to a 2008 declaration, however, the location was shifted into Marantao in 2015 according to another declaration. The recently updated 2018 PRECUP currently states that the Kawayan Torogan is in Pompongan-a-marantao, a barangay (village) of Marawi City, not of Marantao town. The confusion has caused scholars to push for the declaration of the kawayan torogan in Marantao as a National Cultural Treasure, as well. The National Commission for Culture and the Arts has no official statement regarding the issue yet.

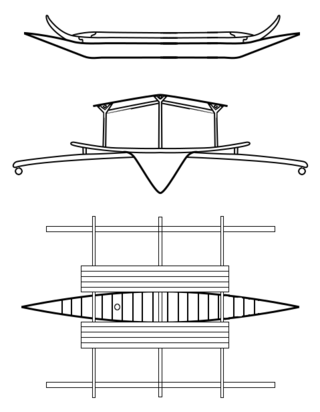

Lepa, also known as lipa or lepa-lepa, are indigenous ships of the Sama-Bajau people in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Malaysia. They were traditionally used as houseboats by the seagoing Sama Dilaut. Since most Sama have abandoned exclusive sea-living, modern lepa are instead used as fishing boats and cargo vessels.

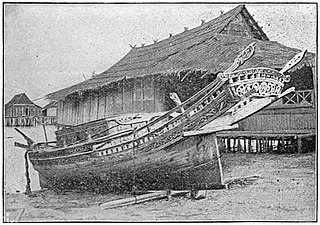

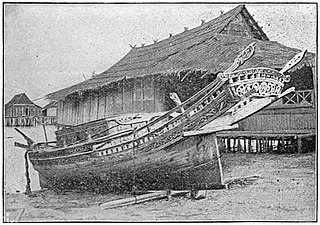

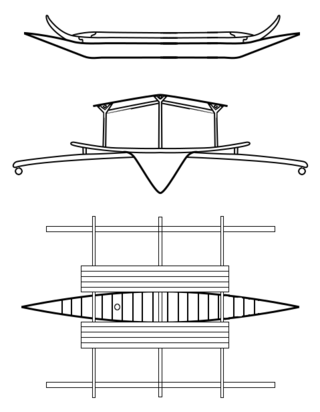

Djenging is a type of large double-outrigger plank boat built by the Sama-Bajau people of the Philippines. It is typically used as a houseboat, though it can be converted to a sailing ship. It was the original type of houseboat used by the Sama-Bajau before it was largely replaced by the lepa after World War II. Larger versions of djenging were also known as balutu or kubu, often elaborately carved with bifurcated extensions on the prow and stern.

Awang are traditional dugout canoes of the Maranao and Maguindanao people in the Philippines. They are used primarily in Lake Lanao, the Pulangi River, and the Liguasan Marsh for fishing or for transporting goods. They have long low hulls that are carved from single trunks of lauan and apitong trees. They have no outriggers but have a single sail or a paddle. The prow and the stern are commonly elaborately decorated with painted designs and okir carvings, usually of the piyako and potiyok a rabong motifs. Some awang are also decorated with a carved prow extension known as the panolong or kalandapon.