The Alhambra is a palace and fortress complex located in Granada, Spain. It is one of the most famous monuments of Islamic architecture and one of the best-preserved palaces of the historic Islamic world, in addition to containing notable examples of Spanish Renaissance architecture.

Granada is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence of four rivers, the Darro, the Genil, the Monachil and the Beiro. Ascribed to the Vega de Granada comarca, the city sits at an average elevation of 738 m (2,421 ft) above sea level, yet is only one hour by car from the Mediterranean coast, the Costa Tropical. Nearby is the Sierra Nevada Ski Station, where the FIS Alpine World Ski Championships 1996 were held.

An alcázar, from Arabic al-Qasr, is a type of Islamic castle or palace in Spain built during Muslim rule between the 8th and 15th centuries. They functioned as homes and regional capitals for governmental figures throughout the Umayyad caliphate and later for Christian rulers following the Iberian Reconquista. The term alcázar is also used for many medieval castles built by Christians on earlier Roman, Visigothic or Islamic fortifications and is frequently used as a synonym for castillo or castle. In Latin America there are also several colonial palaces called alcázars.

The Court of the Lions (Spanish: Patio de los Leones) or Palace of the Lions is a palace in the heart of the Alhambra, a historic citadel formed by a complex of palaces, gardens and forts in Granada, Spain. It was commissioned by the Nasrid sultan Muhammad V of the Emirate of Granada in Al-Andalus. Its construction started in the second period of his reign, between 1362 and 1391 AD. Along with the Alhambra, the palace is part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was minted in Spain's 2011 limited edition of €2 Commemorative Coins.

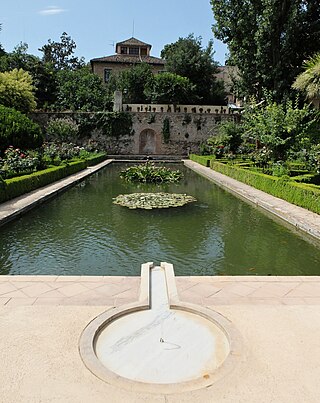

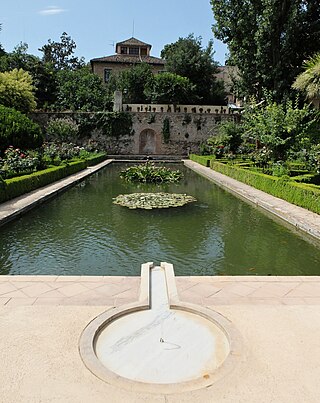

The Generalife was a summer palace and country estate of the Nasrid rulers of the Emirate of Granada in Al-Andalus. It is located directly east of and uphill from the Alhambra palace complex in Granada, Spain.

The Albaicín, also spelled Albayzín, is a neighbourhood of Granada, Spain. It is centered around a hill on the north side of the Darro River which passes through the city. The neighbourhood is notable for its historic monuments and for largely retaining its medieval street plan dating back to the Nasrid period, although it nonetheless went through many physical and demographic changes after the end of the Reconquista in 1492. It was declared a World Heritage Site in 1994, as an extension of the historic site of the nearby Alhambra.

The Palace of Charles V is a Renaissance building in Granada, southern Spain, inside the Alhambra, a former Nasrid palace complex on top of the Sabika hill. Construction began in 1527 but dragged on and was left unfinished after 1637. The palace was only completed after 1923, when Leopoldo Torres Balbás initiated its restoration. The building has never been a home to a monarch and stood roofless until 1967. Today, the building also houses the Alhambra Museum on its ground floor and the Fine Arts Museum of Granada on its upper floor.

The Alcazaba is a palatial fortification in Málaga, Spain, built during the period of Muslim-ruled Al-Andalus. The current complex was begun in the 11th century and was modified or rebuilt multiple times up to the 14th century. It is one of the best-preserved alcazabas in Spain. The Alcazaba is also connected by a walled corridor to the higher Castle of Gibralfaro, and adjacent to the entrance of the Alcazaba are remnants of a Roman theatre dating to the 1st century AD.

The Gate of Bibarrambla or Bibrambla, also known as Puerta del Arenal or Arch of the Ears, was a former city gate in Granada, Spain. Built in the 14th century during the Nasrid period, it stood at the corner of a public square of the same name, Plaza de Bibarrambla. The gate was demolished between 1873 and 1884. In 1935, it was partially reconstructed by Leopoldo Torres Balbás in the woods outside the Alhambra, where it stands today.

The Court of the Myrtles is the central part of the Comares Palace inside the Alhambra palace complex in Granada, Spain. It is located east of the Mexuar and west of the Palace of the Lions. It was begun by the Nasrid sultan Isma'il I in the early 14th century and significantly modified by his successors Yusuf I and Muhammad V later in the same century. In addition to the Court of the Myrtles, the palace's most important element is Hall of Ambassadors, the sultan's throne hall and one of the most impressive chambers in the Alhambra.

The Corral del Carbón, originally al-Funduq al-Jadida, is a 14th-century historic building in the Spanish city of Granada (Andalusia). It is the only funduq or alhóndiga preserved from the Nasrid period in the Iberian Peninsula. The building is located south of the Albaicin quarter, near the present-day Cathedral.

Partal Palace is a palatial structure inside the Alhambra fortress complex located in Granada, Spain. It was originally built in the early 14th century by the Nasrid ruler Muhammad III, making it the oldest surviving palatial structure in the Alhambra.

Dar al-Horra is a former 15th-century Nasrid palace located in the Albaicín quarter of Granada, Spain. Since the early 16th century it was used as part of the Monastery of Santa Isabel la Real. It is now a historic monument.

The Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo is a former Nasrid palace and convent in Granada, Spain. It is located in the Realejo quarter of the city.

The Palacio del Partal Alto, also known as the Palacio de Yusuf III or the Palacio del Conde del Tendilla, is a former palace in the Alhambra, the historic citadel of Granada, Spain. It is the oldest palace in the Alhambra for which any remains have been found. It was built in the reign of the Nasrid ruler Muhammad II. After the conquest of Granada in 1492 it became the residence of the Count of Tendilla, the governor of the Alhambra, until it was confiscated by Philip V in 1717 and subsequently demolished. After excavations in the 20th century, a part of the palace's foundations are visible today in the Partal Gardens.

The Torre de la Cautiva is a tower in the walls of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. It is one of several towers along the Alhambra's northern wall which were converted into a small palatial residence in the 14th century. It is considered an exceptional example of Nasrid domestic architecture from this period.

The Alcazaba is a fortress at the western tip of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. Its name comes from the Arabic term al-qaṣabah, which became Alcazaba in Spanish. It is the oldest surviving part of the Alhambra, having been built by Muhammad I Ibn al-Ahmar, the founder of the Nasrid dynasty, after 1238. It stands on the site of an earlier fortress built by the Zirid kingdom of Granada in the 11th century.

The Mexuar is a section of the Nasrid palace complex in the Alhambra of Granada, Spain. It served as the entrance wing of the Comares Palace, the official palace of the sultan and the state, and it housed various administrative functions. After the 1492 conquest of Granada by Christian Spain the building's main hall was converted into a chapel, though many of the Christian additions were later removed during modern restorations. The palace's two main courtyards were also put to other uses and only their foundations remain visible today.

A mirador is a Spanish term designating a lookout point or a place designed to offer extensive views of the surrounding area. In an architectural context, the term can refer to a tower, balcony, window, or other feature that offers wide views. The term is often applied to Moorish architecture, especially Nasrid architecture, to refer to an elevated room or platform that projects outwards from the rest of a building and offers 180-degree views through windows on three sides. The equivalent term in Arabic is bahw or manāẓir/manẓar.