The Cotton Club was a 20th-century nightclub in New York City. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue from 1923 to 1936, then briefly in the midtown Theater District until 1940. The club operated during the United States' era of Prohibition and Jim Crow era racial segregation. Black people initially could not patronize the Cotton Club, but the venue featured many of the most popular black entertainers of the era, including musicians Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Jimmie Lunceford, Chick Webb, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Fats Waller, Willie Bryant; vocalists Adelaide Hall, Ethel Waters, Cab Calloway, Bessie Smith, Lillie Delk Christian, Aida Ward, Avon Long, the Dandridge Sisters, the Will Vodery choir, The Mills Brothers, Nina Mae McKinney, Billie Holiday, Midge Williams, Lena Horne, and dancers such as Katherine Dunham, Bill Robinson, The Nicholas Brothers, Charles 'Honi' Coles, Leonard Reed, Stepin Fetchit, the Berry Brothers, The Four Step Brothers, Jeni Le Gon and Earl Snakehips Tucker.

Florence Mills, billed as the "Queen of Happiness", was an American cabaret singer, dancer, and comedian.

Charles "Cholly" Atkins was an American dancer and vaudeville performer, who later became noted as the house choreographer for the various artists on the label Motown.

Adelaide Louise Hall was an American-born UK-based jazz singer and entertainer. Her career spanned more than 70 years from 1921 until her death. Early in her career, she was a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance; she became based in the UK after 1938. Hall entered the Guinness Book of World Records in 2003 as the world's most enduring recording artist, having released material over eight consecutive decades. She performed with major artists such as Art Tatum, Ethel Waters, Josephine Baker, Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, Cab Calloway, Fela Sowande, Rudy Vallee, and Jools Holland, and recorded as a jazz singer with Duke Ellington and with Fats Waller.

Charles "Honi" Coles was an American actor and tap dancer, who was inducted posthumously into the American Tap Dance Hall of Fame in 2003. He had a distinctive personal style that required technical precision, high-speed tapping, and a close-to-the-floor style where "the legs and feet did the work". Coles was also half of the professional tap dancing duo Coles and Atkins, whose specialty was performing with elegant style through various tap steps such as "swing dance", "over the top", "bebop", "buck and wing", and "slow drag".

Joseph Christopher Columbus Morris, better known as Crazy Chris Columbo or just Chris Columbo, was an American jazz drummer. He was sometimes credited as Joe Morris on record, though he is no relation to free jazz guitarist Joe Morris or trumpeter Joe Morris.

"Jumpin' at the Woodside" is a song first recorded in 1938 by the Count Basie Orchestra, and considered one of the band's signature tunes. When first released it reached number 11 on the Billboard charts and remained on them for four weeks. Since then, it has become a frequently recorded jazz standard.

Lloyd Nelson Trotman, born in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, was an American jazz bassist, who backed numerous jazz, dixieland, R&B, and rock and roll artists in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. He resided in Huntington, Long Island, New York between 1962 and 2007, and prior to that in East Elmhurst, Queens, New York from 1945 to 1962. He worked primarily out of New York City. He provided the bass line on Ben E. King's "Stand by Me".

Jimmy Mordecai also known as James Mordecai was an American, Harlem-based jazz tap dancer in the 1920s and 1930s. He featured in the 1929 short film St. Louis Blues, and starred in the 1930 Vitaphone Varieties musical short film, Yarmekraw, based on James P. Johnson's song of the same name.

Leonard Harper was a producer, stager, and choreographer in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and 1930s.

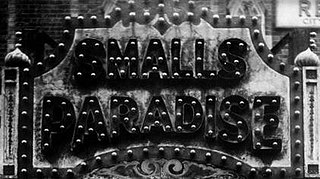

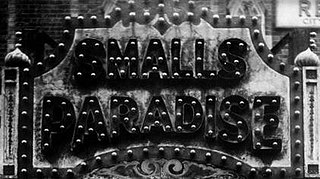

Smalls Paradise, was a nightclub in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. Located in the basement of 2294 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard at 134th Street, it opened in 1925 and was owned by Ed Smalls (né Edwin Alexander Smalls; 1882–1976). At the time of the Harlem Renaissance, Smalls Paradise was the only one of the well-known Harlem night clubs to be owned by an African-American and integrated. Other major Harlem night clubs admitted only white patrons unless the person was an African-American celebrity.

Club Harlem was a nightclub at 32 North Kentucky Avenue in the Northside neighborhood of Atlantic City, New Jersey. Founded in 1935 by Leroy "Pop" Williams, it was the city's premier club for black jazz performers. Like its Harlem counterpart, the Cotton Club, many of Club Harlem's guests were white, wealthy and eager to experience a night of African-American entertainment.

Kentucky Avenue Renaissance Festival, also known as the Historical Kentucky Avenue Renaissance Festival, is a street fair held each summer in the former black entertainment district of Atlantic City, New Jersey. Founded in 1992, it appeared annually until 2001, and then resumed in 2011. Held on and around the site of the razed Club Harlem, the weekend fair commemorates the R&B and jazz nightspots that once lined Kentucky Avenue and that attracted both black and white clientele in its heyday from the 1940s through 1960s. The festival features live performances by R&B and jazz musicians and bands, dance performances, street performers, arts and crafts for children, and food concessions, and draws hundreds of attendees.

Grace's Little Belmont was a jazz music bar and lounge in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Located at 37 North Kentucky Avenue, it was one of the four popular black nightclubs situated on that street between the mid-1930s and mid-1970s; the others were Club Harlem, the Paradise Club, and the Wonder Gardens. The Little Belmont was located across the street from Club Harlem, with which it often shared performers and patrons. Wild Bill Davis and his swing and jazz quartet were featured summer performers from 1950 through the mid-1960s, and Elvera M. "Baby" Sanchez, mother of Sammy Davis Jr., worked at the bar. The club closed in the mid-1970s and was later demolished.

Wonder Gardens was a jazz and R&B nightclub at 1601 Arctic Avenue in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Established around 1929, it was one of four black-owned nightclubs in the black entertainment district on Kentucky Avenue. Between the Wonder Gardens, Club Harlem, the Paradise Club, and Grace's Little Belmont, the music played all night and into the morning in the district's heyday in the 1940s through 1960s. Presenting both popular jazz musicians and new talent, the Wonder Gardens provided early exposure for Dan Fogel, Harvey Mason, George Benson, and the Commodores. Over the years, the music changed from jazz to rock, soul, and pop music. In 1979 the club was renovated, redecorated and renamed the Latin Wonder Gardens, featuring live Afro-Cuban musical entertainment. In 1991 it underwent a second renovation and name change to the New Wonder Gardens, featuring Latin, jazz, R&B, hiphop, and reggae acts. The club was sold in 2001 and was later demolished.

Wash's Restaurant, later called Wash & Sons' Seafood Restaurant, Wash's Inn, and Wash's Catering, was an African-American family-owned and operated soul food restaurant that was in business for over 70 years, first in Atlantic City and then in Pleasantville, New Jersey. Established by Clifton and Alma Washington at 35 N. Kentucky Avenue, Atlantic City, in 1937, the original 20-seat location attained celebrity status for hosting the performers and patrons of the nightclubs in the Kentucky Avenue black entertainment district. The restaurant was known for its sausage sandwiches and soul food, and also served breakfast to customers leaving the 6 a.m. show at Club Harlem.

A class act is a performance, personal trait or behavior that is distinctive and of high quality. As a noun phrase, it is typically used to refer to a single person, a team or an organization.

The Cotton Club Boys were African American chorus line entertainers who, from 1934, performed class act dance routines in musical revues produced by the Cotton Club until 1940, when the club closed, then as part of Cab Calloway's revue on tour through 1942.

Black and Tan clubs were nightclubs in the United States in the early 20th century catering to the black and mixed-race ("tan") population. They flourished in the speakeasy era and were often popular places of entertainment linked to the early jazz years. With time the definition simply came to mean black and white clientele.

Miller Brothers and Lois, a renowned tap dance class act team, comprising Danny Miller, George Miller and Lois Bright, was a peak of platform dancing with the tall and graceful Lois said to distinguish the trio. The group performed the majority of their act on platforms of various heights, with the initial platform spelling out M-I-L-L-E-R. They performed over-the-tops, barrel turns and wings on six-foot-high pedestals. They toured theatres coast to coast with Jimmy Lunceford and his Orchestra, Cab Calloway and his Orchestra, and the Count Basie Band.