Lakeview is one of the 77 community areas of Chicago, Illinois. Lakeview is located on the city's North Side and is bordered by West Diversey Parkway on the south, West Irving Park Road on the north, North Ravenswood Avenue on the west, and the shore of Lake Michigan on the east. The Uptown community area is to Lakeview's north, Lincoln Square to its northwest, North Center to its west, and Lincoln Park to its south. The 2020 population of Lakeview was 103,050 residents, making it the second-largest Chicago community area by population.

The Cotton Club was a 20th-century nightclub in New York City. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue from 1923 to 1936, then briefly in the midtown Theater District until 1940. The club operated during the United States' era of Prohibition and Jim Crow era racial segregation. Black people initially could not patronize the Cotton Club, but the venue featured many of the most popular black entertainers of the era, including musicians Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Jimmie Lunceford, Chick Webb, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Fats Waller, Willie Bryant; vocalists Adelaide Hall, Ethel Waters, Cab Calloway, Bessie Smith, Lillie Delk Christian, Aida Ward, Avon Long, the Dandridge Sisters, the Will Vodery choir, The Mills Brothers, Nina Mae McKinney, Billie Holiday, Midge Williams, Lena Horne, and dancers such as Katherine Dunham, Bill Robinson, The Nicholas Brothers, Charles 'Honi' Coles, Leonard Reed, Stepin Fetchit, the Berry Brothers, The Four Step Brothers, Jeni Le Gon and Earl Snakehips Tucker.

The Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) was the private operator of New York City's original underground subway line that opened in 1904, as well as earlier elevated railways and additional rapid transit lines in New York City. The IRT was purchased by the city on June 12, 1940, along with the younger BMT and IND systems, to form the modern New York City Subway. The former IRT lines are now the A Division or IRT Division of the Subway.

Frank Grillo known professionally as Machito, was a Latin jazz musician who helped refine Afro-Cuban jazz and create both Cubop and salsa music. He was raised in Havana with his sister, singer Graciela.

Prudencio Mario Bauzá Cárdenas was an Afro-Cuban jazz, and jazz musician. He was among the first to introduce Cuban music to the United States by bringing Cuban musical styles to the New York City jazz scene. While Cuban bands had had popular jazz tunes in their repertoire for years, Bauzá's composition "Tangá" was the first piece to blend jazz harmony and arranging technique, with jazz soloists and Afro-Cuban rhythms. It is considered the first true Afro-Cuban jazz tune.

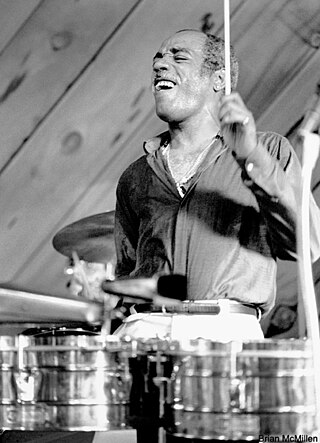

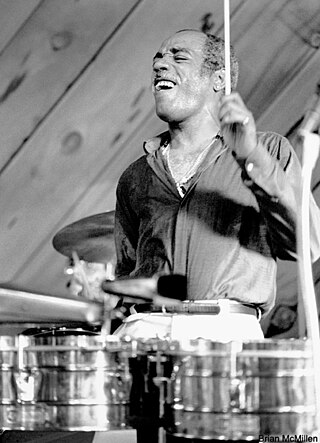

William Correa, better known by his stage name Willie Bobo, was an American Latin jazz percussionist of Puerto Rican descent. Bobo rejected the stereotypical expectations of Latino music and was noted for his versatility as an authentic Latin percussionist as well as a jazz drummer easily moving stylistically from jazz, Latin and rhythm and blues music.

Clicquot Club was a nightclub at 15 North Illinois Avenue in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in the heart of the city. Billed as the club that "never closed", it became notorious as an illegal gambling spot in the city.

Joseph Christopher Columbus Morris, better known as Crazy Chris Columbo or just Chris Columbo, was an American jazz drummer. He was sometimes credited as Joe Morris on record, though he is no relation to free jazz guitarist Joe Morris or trumpeter Joe Morris.

Dan Fogel is an American jazz organist playing the Hammond B-3 organ.

Missouri Avenue Beach, often referred to as "Chicken Bone Beach," is a lifeguarded beach on the Jersey Shore. It was an early and mid-twentieth-century Black resort destination and racially segregated section of the Atlantic Ocean beach near the Northside neighborhood of Atlantic City, New Jersey . The name was initially most likely a pejorative or condescending reference to the packed lunches brought by beachgoers who were not permitted by unspoken sentiment in many dining establishments, but the Black community has reclaimed the name as a point of resistance and pride. The beach is now home to swimming, sunbathing, jazz and other local events.

Club Harlem was a nightclub at 32 North Kentucky Avenue in the Northside neighborhood of Atlantic City, New Jersey. Founded in 1935 by Leroy "Pop" Williams, it was the city's premier club for black jazz performers. Like its Harlem counterpart, the Cotton Club, many of Club Harlem's guests were white, wealthy and eager to experience a night of African-American entertainment.

The Paradise Club or Club Paradise was a nightclub and jazz club at 220 North Illinois Avenue in Atlantic City, New Jersey. It was one of two major black jazz clubs in Atlantic City during its heyday from the 1920s through 1950s, the other being Club Harlem. Entertaining a predominantly white clientele, it was known for its raucous floor shows featuring gyrating black dancers accompanied by high-energy jazz bands led by the likes of Count Basie, Jimmie Lunceford, and Lucky Millinder. In 1954 the Paradise Club merged with Club Harlem under joint ownership.

Babette's or Babette's Supper Club was a supper club and bar at 2211 Pacific Avenue on the Boardwalk of Atlantic City, New Jersey, United States. It operated from the early 1920s onwards and was sold in 1950. The bar was designed like a ship's hull. In the backroom was a gambling den, which was investigated by the federal authorities and raided in 1943.

Ollie Potter was an American female blues singer, notably of Cleveland and New York City, and a dancer, particularly of the shimmy style.

Kentucky Avenue Renaissance Festival, also known as the Historical Kentucky Avenue Renaissance Festival, is a street fair held each summer in the former black entertainment district of Atlantic City, New Jersey. Founded in 1992, it appeared annually until 2001, and then resumed in 2011. Held on and around the site of the razed Club Harlem, the weekend fair commemorates the R&B and jazz nightspots that once lined Kentucky Avenue and that attracted both black and white clientele in its heyday from the 1940s through 1960s. The festival features live performances by R&B and jazz musicians and bands, dance performances, street performers, arts and crafts for children, and food concessions, and draws hundreds of attendees.

Grace's Little Belmont was a jazz music bar and lounge in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Located at 37 North Kentucky Avenue, it was one of the four popular black nightclubs situated on that street between the mid-1930s and mid-1970s; the others were Club Harlem, the Paradise Club, and the Wonder Gardens. The Little Belmont was located across the street from Club Harlem, with which it often shared performers and patrons. Wild Bill Davis and his swing and jazz quartet were featured summer performers from 1950 through the mid-1960s, and Elvera M. "Baby" Sanchez, mother of Sammy Davis Jr., worked at the bar. The club closed in the mid-1970s and was later demolished.

Wash's Restaurant, later called Wash & Sons' Seafood Restaurant, Wash's Inn, and Wash's Catering, was an African-American family-owned and operated soul food restaurant that was in business for over 70 years, first in Atlantic City and then in Pleasantville, New Jersey. Established by Clifton and Alma Washington at 35 N. Kentucky Avenue, Atlantic City, in 1937, the original 20-seat location attained celebrity status for hosting the performers and patrons of the nightclubs in the Kentucky Avenue black entertainment district. The restaurant was known for its sausage sandwiches and soul food, and also served breakfast to customers leaving the 6 a.m. show at Club Harlem.

The Golden Gate Ballroom, originally named the "State Palace Ballroom", was a luxurious ballroom located at the intersection of Lenox Avenue and 142nd Street in Harlem in New York City. It was allegedly the largest public auditorium in Harlem, with 25,000 square feet and a capacity of about 5,000 people on the dance floor in addition to several thousand spectators.

"King" Solomon Hicks is an American guitarist, blues, jazz singer, and composer. His style of music ranges from jazz, blues, classical, gospel, R&B, funk, Afro-Cuban, and classic rock. Hicks has been a blues guitarist since he was 13. He plays a Benedetto GA35 guitar. Benedetto jazz guitars are hand crafted by Robert Benedetto an American luthier of archtop jazz guitars. He teaches beginning and advanced guitar along with music theory.