A soft drink is any water-based flavored drink, usually but not necessarily carbonated, and typically including added sweetener. Flavors used can be natural or artificial. The sweetener may be a sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, fruit juice, a sugar substitute, or some combination of these. Soft drinks may also contain caffeine, colorings, preservatives and other ingredients.

The Chicago Tylenol murders were a series of poisoning deaths resulting from drug tampering in the Chicago metropolitan area in 1982. The victims consumed Tylenol-branded acetaminophen capsules that had been laced with potassium cyanide. Seven people died in the original poisonings, and there were several more deaths in subsequent copycat crimes.

Poisoned candy myths are mostly urban legends about malevolent strangers intentionally hiding poisons, drugs, or sharp objects such as razor blades in candy, which they then distribute with the intent of harming random children, especially during Halloween trick-or-treating. These myths, originating in the United States, serve as modern cautionary tales to children and parents and repeat two themes that are common in urban legends: danger to children and contamination of food.

The Matsumoto sarin attack was an attempted assassination perpetrated by members of the Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, Japan on the night of June 27, 1994. Eight people were killed and more than 500 were harmed by sarin aerosol that was released from a converted refrigerator truck in the Kaichi Heights area. The attack was perpetrated nine months before the better-known Tokyo subway sarin attack.

Ramune is a Japanese carbonated soft drink. It was introduced in 1884 in Kobe by the Scottish pharmacist Alexander Cameron Sim. Ramune is available in a Codd-neck bottle, a heavy glass bottle whose mouth is sealed by a round marble due to the pressure of the carbonated contents. The name ramune is derived from a Japanese borrowing of the English word lemonade.

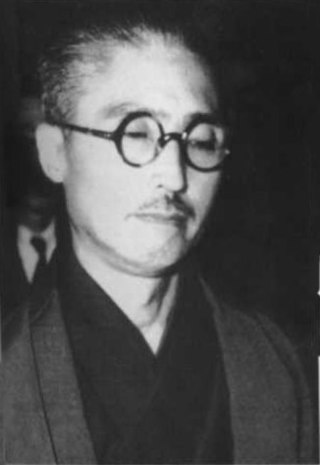

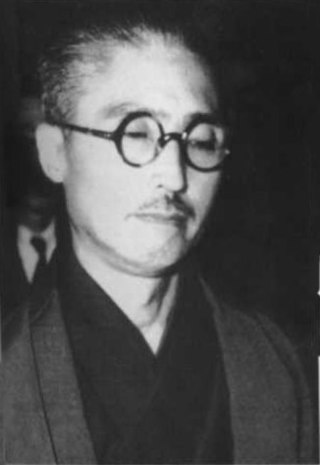

Sadamichi Hirasawa was a Japanese tempera painter. He was convicted of mass poisoning and sentenced to death. Due to strong suspicions that he was innocent, no justice minister ever signed his death warrant.

Paraquat (trivial name; ), or N,N′-dimethyl-4,4′-bipyridinium dichloride (systematic name), also known as methyl viologen, is a toxic organic compound with the chemical formula [(C6H7N)2]Cl2. It is classified as a viologen, a family of redox-active heterocycles of similar structure. This salt is one of the most widely used herbicides worldwide. It is quick-acting and non-selective, killing green plant tissue on contact.

These are lists of poisonings, deliberate and accidental, in chronological order by the date of death of the victim(s). They include mass poisonings, confirmed attempted poisonings, suicides, fictional poisonings and people who are known or suspected to have killed multiple people.

Asahi Soft Drinks Co., Ltd is a soft drink company founded in 1982 and headquartered in the Azuma-bashi district of Sumida, Tokyo, Japan. It is a subsidiary of Asahi Breweries. The company sponsors the Asahi Soft Drink Challengers, an American football team in the Japanese X-League, as well as a futsal team.

Diquat is the ISO common name for an organic dication that, as a salt with counterions such as bromide or chloride is used as a contact herbicide that produces desiccation and defoliation. Diquat is no longer approved for use in the European Union, although its registration in many other countries including the USA is still valid.

And Be a Villain is a Nero Wolfe detective novel by Rex Stout, first published by the Viking Press in 1948. The story was collected in the omnibus volumes Full House and Triple Zeck.

Cheerio is a Japanese carbonated soft drink manufactured by the Cheerio Corporation. The drink comes in multiple flavors, and was introduced in 1963. The drinks used to be sold in glass bottles, similar to those used for Ramune. In recent years, with the proliferation of steel and aluminum cans and PET bottles, Cheerio in glass bottles is only available in the Chūbu region southwest of Tokyo, as well as three vending units in Kanagawa Prefecture.

Canned coffee is a pre-brewed version of the beverage, sold ready to drink. It is particularly popular in Japan, South Korea, and elsewhere across Asia, and produced in a number of styles and by a large number of companies. Canned coffee is available in supermarkets and convenience stores, with large numbers of cans also being sold in vending machines that offer heated cans in the autumn and winter, and cold cans in the warm months.

Nigori or nigorizake is a variety of sake, an alcoholic beverage produced from rice. Its name translates roughly to "cloudy" because of its appearance. It is about 12–17% alcohol by volume, averaging 15% with some as high as 20%.

Oronamin C Drink, produced by Otsuka Chemical Holdings Co., Ltd., is a carbonated beverage available in Japan. It is commonly called Oronamin C or Oronamin. Its name is similar to the Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. product "Arinamin" and its name comes from Otsuka's own Oronine H Ointment and one of its ingredients, vitamin C. Oronamin C was named after the Oronine H Ointment in hopes that it would prove to be equally successful.

Strychnine poisoning is poisoning induced by strychnine. It can be fatal to humans and other animals and can occur by inhalation, swallowing or absorption through eyes or mouth. It produces some of the most dramatic and painful symptoms of any known toxic reaction, making it quite noticeable and a common choice for assassinations and poison attacks. For this reason, strychnine poisoning is often portrayed in literature and film, such as the murder mysteries written by Agatha Christie.

Smoking in Japan is practiced by around 20,000,000 people, and the nation is one of the world's largest tobacco markets, though tobacco use has been declining in recent years.

Tampering can refer to many forms of sabotage but the term is often used to mean intentional modification of products in a way that would make them harmful to the consumer. This threat has prompted manufacturers to make products that are either difficult to modify or at least difficult to modify without warning the consumer that the product has been tampered with. Since the person making the modification is typically long gone by the time the crime is discovered, many of these cases are never solved.

POKKA SAPPORO Food & Beverage Ltd. is a corporation headquartered in Sapporo, Japan, which sells canned or bottled coffee, flavored tea and an assortment of other beverages.