Psychology is the study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both conscious and unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feelings, and motives. Psychology is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries between the natural and social sciences. Biological psychologists seek an understanding of the emergent properties of brains, linking the discipline to neuroscience. As social scientists, psychologists aim to understand the behavior of individuals and groups.

Psychotherapy is the use of psychological methods, particularly when based on regular personal interaction, to help a person change behavior, increase happiness, and overcome problems. Psychotherapy aims to improve an individual's well-being and mental health, to resolve or mitigate troublesome behaviors, beliefs, compulsions, thoughts, or emotions, and to improve relationships and social skills. Numerous types of psychotherapy have been designed either for individual adults, families, or children and adolescents. Certain types of psychotherapy are considered evidence-based for treating some diagnosed mental disorders; other types have been criticized as pseudoscience.

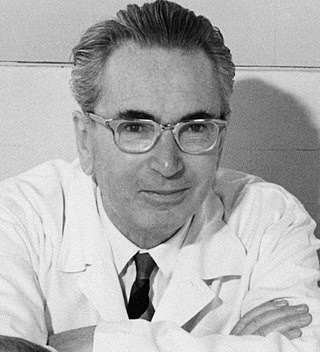

Viktor Emil Frankl was an Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, who founded logotherapy, a school of psychotherapy that describes a search for a life's meaning as the central human motivational force. Logotherapy is part of existential and humanistic psychology theories.

Humanistic psychology is a psychological perspective that arose in the mid-20th century in answer to two theories: Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theory and B. F. Skinner's behaviorism. Thus, Abraham Maslow established the need for a "third force" in psychology. The school of thought of humanistic psychology gained traction due to key figure Abraham Maslow in the 1950s during the time of the humanistic movement. It was made popular in the 1950s by the process of realizing and expressing one's own capabilities and creativity.

Logotherapy was developed by neurologist and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl and is based on the premise that the primary motivational force of an individual is to find a meaning in life. Frankl describes it as "the Third Viennese School of Psychotherapy" along with Freud's psychoanalysis and Adler's individual psychology.

Integrative psychotherapy is the integration of elements from different schools of psychotherapy in the treatment of a client. Integrative psychotherapy may also refer to the psychotherapeutic process of integrating the personality: uniting the "affective, cognitive, behavioral, and physiological systems within a person".

Person-centered therapy, also known as person-centered psychotherapy, person-centered counseling, client-centered therapy and Rogerian psychotherapy, is a form of psychotherapy developed by psychologist Carl Rogers and colleagues beginning in the 1940s and extending into the 1980s. Person-centered therapy seeks to facilitate a client's actualizing tendency, "an inbuilt proclivity toward growth and fulfillment", via acceptance, therapist congruence (genuineness), and empathic understanding.

Existential psychotherapy is a form of psychotherapy based on the model of human nature and experience developed by the existential tradition of European philosophy. It focuses on concepts that are universally applicable to human existence including death, freedom, responsibility, and the meaning of life. Instead of regarding human experiences such as anxiety, alienation and depression as implying the presence of mental illness, existential psychotherapy sees these experiences as natural stages in a normal process of human development and maturation. In facilitating this process of development and maturation existential psychotherapy involves a philosophical exploration of an individual's experiences while stressing the individual's freedom and responsibility to facilitate a higher degree of meaning and well-being in his or her life.

Salutogenesis is the study of the origins of health and focuses on factors that support human health and well-being, rather than on factors that cause disease (pathogenesis). More specifically, the "salutogenic model" was originally concerned with the relationship between health, stress, and coping through a study of Holocaust survivors. Despite going through the dramatic tragedy of the holocaust, some survivors were able to thrive later in life. The discovery that there must be powerful health causing factors led to the development of salutogenesis. The term was coined by Aaron Antonovsky (1923-1994), a professor of medical sociology. The salutogenic question posed by Aaron Antonovsky is, "How can this person be helped to move toward greater health?"

Emotionally focused therapy and emotion-focused therapy (EFT) are a set of related approaches to psychotherapy with individuals, couples, or families. EFT approaches include elements of experiential therapy, systemic therapy, and attachment theory. EFT is usually a short-term treatment. EFT approaches are based on the premise that human emotions are connected to human needs, and therefore emotions have an innately adaptive potential that, if activated and worked through, can help people change problematic emotional states and interpersonal relationships. Emotion-focused therapy for individuals was originally known as process-experiential therapy, and it is still sometimes called by that name.

Clark E. Moustakas was an American psychologist and one of the leading experts on humanistic and clinical psychology. He helped establish the Association for Humanistic Psychology and the Journal of Humanistic Psychology. He is the author of numerous books and articles on humanistic psychology, education and human science research. His most recent books: Phenomenological Research Methods; Heuristic Research; Existential Psychotherapy and the Interpretation of Dreams; Being-In, Being-For, Being-With; and Relationship Play Therapy are valuable additions to research and clinical literature. His focus at the Michigan School of Professional Psychology was the integration of philosophy, research and psychology in the education and training of humanistic clinical psychologists.

Future-oriented therapy (FOT) and future-directed therapy (FDT) are approaches to psychotherapy that place greater emphasis on the future than on the past or present.

Existential counselling is a philosophical form of counselling which addresses the situation of a person's life and situates the person firmly within the predictable challenges of the human condition.

Kirk J. Schneider is a psychologist and psychotherapist who has taken a leading role in the advancement of existential-humanistic therapy, and existential-integrative therapy. Schneider is also the current editor of the Journal of Humanistic Psychology. His major books are Existential-Humanistic Therapy (2010), Existential-Integrative Therapy (2008), The Handbook of Humanistic Psychology (2001), The Psychology of Existence (1995), Rediscovery of Awe (2004), Awakening to Awe (2009), and "The Polarized Mind" (2013).

Death anxiety is anxiety caused by thoughts of one's own death, and is also referred to as thanatophobia. Individuals affected by this kind of anxiety experience challenges and adversities in many aspects of their lives. Death anxiety is different from necrophobia, which refers to an irrational or disproportionate fear of dead bodies or of anything associated with death. Death anxiety has been found to affect people of differing demographic groups as well, such as men versus women, young versus old, etc.

In psychology, meaning-making is the process of how people construe, understand, or make sense of life events, relationships, and the self.

Second wave positive psychology is a therapeutic approach in psychology that attempts to bring out the best in individuals and society by incorporating the dark side of human existence through the dialectical principles of yin and yang. This represents a distinct shift from focusing on individual happiness and success to the dual vision of individual well-being and collective humanity. PP 2.0 is more about bringing out the "better angels of our nature" than achieving optimal happiness or personal success. The approach posits that empathy, compassion, reason, justice, and self-transcendence will improve humans, both individually and collectively. PP 2.0 centers around the universal human capacity for meaning-seeking and meaning-making in achieving optimal human functioning under both desirable and undesirable conditions. This emerging movement is a response to perceived problems of what some have called "positive psychology as usual."

The International Network on Personal Meaning (INPM) is a nonprofit organization devoted to advancing meaning-centred research and interventions. It was founded by Paul T. P. Wong in 1998. Inspired by Viktor Frankl's logotherapy, Wong wanted to expand Frankl's vision to include the contemporary positive psychology movement. Therefore, the INPM provides a "big tent" for both existential-humanistic psychologists and positive psychologists in their biennial International Meaning Conferences and their journal, the International Journal of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy.

Jacob "Jacky" Lomranz is a professor emeritus at The School of Psychological Sciences at Tel Aviv University. He was a former head of the M.A. program for clinical-gerontological psychology at the Ruppin Academic Center.

Elisabeth Lukas is an Austrian psychiatrist and is one of the central figures in logotherapy, a branch of psychotherapy founded by Viktor Frankl. Lukas is an author of 30 books, translated into 16 languages.