Crystallography is the branch of science devoted to the study of molecular and crystalline structure and properties. The word crystallography is derived from the Ancient Greek word κρύσταλλος, and γράφειν. In July 2012, the United Nations recognised the importance of the science of crystallography by proclaiming 2014 the International Year of Crystallography.

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science of determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract in specific directions. By measuring the angles and intensities of the X-ray diffraction, a crystallographer can produce a three-dimensional picture of the density of electrons within the crystal and the positions of the atoms, as well as their chemical bonds, crystallographic disorder, and other information.

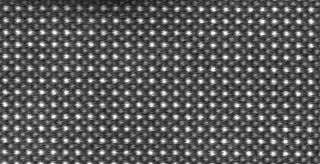

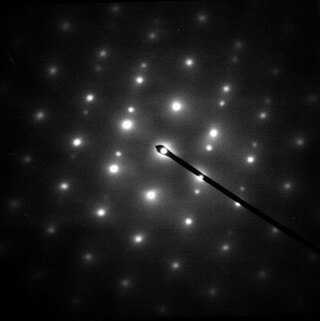

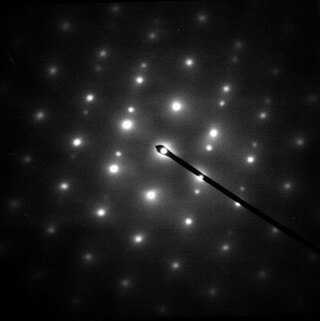

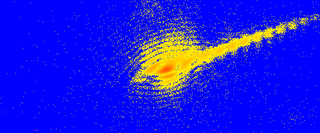

Electron diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of electron beams due to elastic interactions with atoms. It occurs due to elastic scattering, when there is no change in the energy of the electrons. The negatively charged electrons are scattered due to Coulomb forces when they interact with both the positively charged atomic core and the negatively charged electrons around the atoms. The resulting map of the directions of the electrons far from the sample is called a diffraction pattern, see for instance Figure 1. Beyond patterns showing the directions of electrons, electron diffraction also plays a major role in the contrast of images in electron microscopes.

Neutron diffraction or elastic neutron scattering is the application of neutron scattering to the determination of the atomic and/or magnetic structure of a material. A sample to be examined is placed in a beam of thermal or cold neutrons to obtain a diffraction pattern that provides information of the structure of the material. The technique is similar to X-ray diffraction but due to their different scattering properties, neutrons and X-rays provide complementary information: X-Rays are suited for superficial analysis, strong x-rays from synchrotron radiation are suited for shallow depths or thin specimens, while neutrons having high penetration depth are suited for bulk samples.

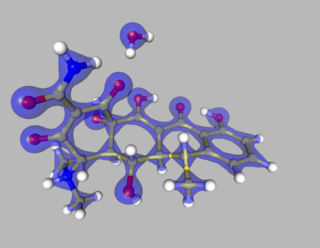

A chemical structure of a molecule is a spatial arrangement of its atoms and their chemical bonds. Its determination includes a chemist's specifying the molecular geometry and, when feasible and necessary, the electronic structure of the target molecule or other solid. Molecular geometry refers to the spatial arrangement of atoms in a molecule and the chemical bonds that hold the atoms together and can be represented using structural formulae and by molecular models; complete electronic structure descriptions include specifying the occupation of a molecule's molecular orbitals. Structure determination can be applied to a range of targets from very simple molecules to very complex ones.

The Ewald sphere is a geometric construction used in electron, neutron, and x-ray diffraction which shows the relationship between:

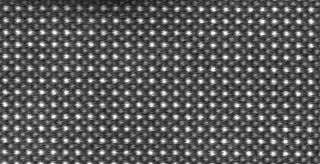

Electron crystallography is a subset of methods in electron diffraction focusing upon detailed determination of the positions of atoms in solids using a transmission electron microscope (TEM). It can involve the use of high-resolution transmission electron microscopy images, electron diffraction patterns including convergent-beam electron diffraction or combinations of these. It has been successful in determining some bulk structures, and also surface structures. Two related methods are low-energy electron diffraction which has solved the structure of many surfaces, and reflection high-energy electron diffraction which is used to monitor surfaces often during growth.

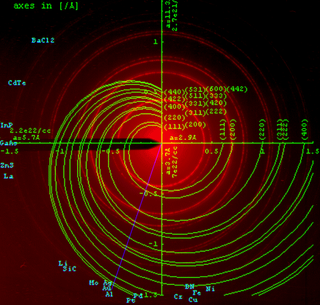

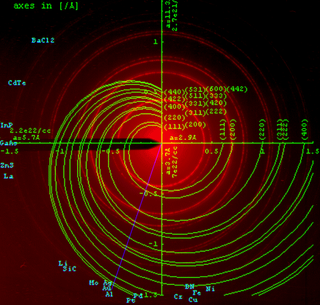

Powder diffraction is a scientific technique using X-ray, neutron, or electron diffraction on powder or microcrystalline samples for structural characterization of materials. An instrument dedicated to performing such powder measurements is called a powder diffractometer.

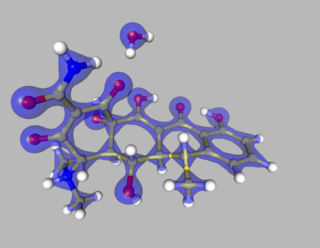

In X-ray crystallography, a difference density map or Fo–Fc map shows the spatial distribution of the difference between the measured electron density of the crystal and the electron density explained by the current model.

Multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction is a technique used in X-ray crystallography that facilitates the determination of the three-dimensional structure of biological macromolecules via solution of the phase problem.

Molecular replacement (MR) is a method of solving the phase problem in X-ray crystallography. MR relies upon the existence of a previously solved protein structure which is similar to our unknown structure from which the diffraction data is derived. This could come from a homologous protein, or from the lower-resolution protein NMR structure of the same protein.

X-ray diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of X-ray beams due to interactions with the electrons around atoms. It occurs due to elastic scattering, when there is no change in the energy of the waves. The resulting map of the directions of the X-rays far from the sample is called a diffraction pattern. It is different from X-ray crystallography which exploits X-ray diffraction to determine the arrangement of atoms in materials, and also has other components such as ways to map from experimental diffraction measurements to the positions of atoms.

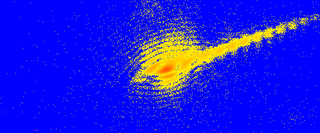

Coherent diffractive imaging (CDI) is a "lensless" technique for 2D or 3D reconstruction of the image of nanoscale structures such as nanotubes, nanocrystals, porous nanocrystalline layers, defects, potentially proteins, and more. In CDI, a highly coherent beam of X-rays, electrons or other wavelike particle or photon is incident on an object.

Isomorphous replacement (IR) is historically the most common approach to solving the phase problem in X-ray crystallography studies of proteins. For protein crystals this method is conducted by soaking the crystal of a sample to be analyzed with a heavy atom solution or co-crystallization with the heavy atom. The addition of the heavy atom (or ion) to the structure should not affect the crystal formation or unit cell dimensions in comparison to its native form, hence, they should be isomorphic.

Single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) is a technique used in X-ray crystallography that facilitates the determination of the structure of proteins or other biological macromolecules by allowing the solution of the phase problem. In contrast to multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD), SAD uses a single dataset at a single appropriate wavelength.

A crystallographic database is a database specifically designed to store information about the structure of molecules and crystals. Crystals are solids having, in all three dimensions of space, a regularly repeating arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules. They are characterized by symmetry, morphology, and directionally dependent physical properties. A crystal structure describes the arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules in a crystal..

The Multipole Density Formalism is an X-ray crystallography method of electron density modelling proposed by Niels K. Hansen and Philip Coppens in 1978. Unlike the commonly used Independent Atom Model, the Hansen-Coppens Formalism presents an aspherical approach, allowing one to model the electron distribution around a nucleus separately in different directions and therefore describe numerous chemical features of a molecule inside the unit cell of an examined crystal in detail.

In crystallography, direct methods is a set of techniques used for structure determination using diffraction data and a priori information. It is a solution to the crystallographic phase problem, where phase information is lost during a diffraction measurement. Direct methods provides a method of estimating the phase information by establishing statistical relationships between the recorded amplitude information and phases of strong reflections.

Quantum crystallography is a branch of crystallography that investigates crystalline materials within the framework of quantum mechanics, with analysis and representation, in position or in momentum space, of quantities like wave function, electron charge and spin density, density matrices and all properties related to them. Like the quantum chemistry, Quantum crystallography involves both experimental and computational work. The theoretical part of quantum crystallography is based on quantum mechanical calculations of atomic/molecular/crystal wave functions, density matrices or density models, used to simulate the electronic structure of a crystalline material. While in quantum chemistry, the experimental works mainly rely on spectroscopy, in quantum crystallography the scattering techniques play the central role, although spectroscopy as well as atomic microscopy are also sources of information.

This is a timeline of crystallography.