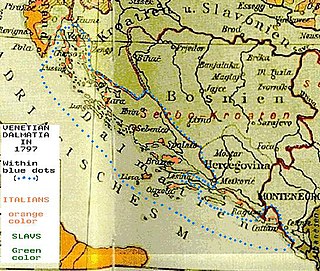

Dalmatia is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Central Croatia, Slavonia, and Istria, located on the east shore of the Adriatic Sea in Croatia.

Giorgio da Sebenico or Giorgio Orsini or Juraj Dalmatinac was a Venetian sculptor and architect from Dalmatia, who worked mainly in Sebenico, and in the city of Ancona, then a maritime republic.

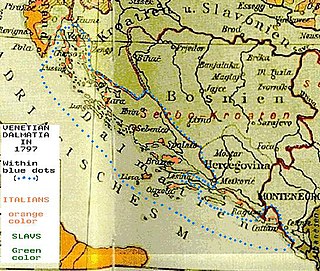

Dalmatian Italians are the historical Italian national minority living in the region of Dalmatia, now part of Croatia and Montenegro.

The Italian language is an official minority language in Croatia, with many schools and public announcements published in both languages. Croatia's proximity and cultural connections to Italy have led to a relatively large presence of Italians in Croatia.

The Governorate of Dalmatia was an administrative division of the Kingdom of Italy, established in 1941, following the military conquest of Yugoslavian Dalmatia by General Vittorio Ambrosio, during World War II. It had the provisional purpose of progressively importing Italian national legislation in Dalmatia in place of the previous one, thus fully integrating it into the Kingdom of Italy.

The Autonomist Party was an Italian-Dalmatianist political party in the Dalmatian political scene, that existed for around 70 years of the 19th century and until World War I. Its goal was to maintain the autonomy of the Kingdom of Dalmatia within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, as opposed to the unification with the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. The Autonomist Party has been accused of secretly having been a pro-Italian movement due to their defense of the rights of ethnic Italians in Dalmatia. The Autonomist Party did not claim to be an Italian movement, and indicated that it sympathized with a sense of heterogeneity amongst Dalmatians in opposition to ethnic nationalism. In the 1861 elections, the Autonomists won twenty-seven seats in Dalmatia, while Dalmatia's Croatian nationalist movement, the National Party, won only fourteen seats. This number rapidly decreased: already in 1870 autonomists lost their majority in the Diet, while in 1908 they won just 6 out of 43 seats.

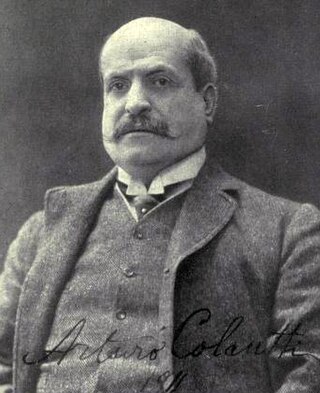

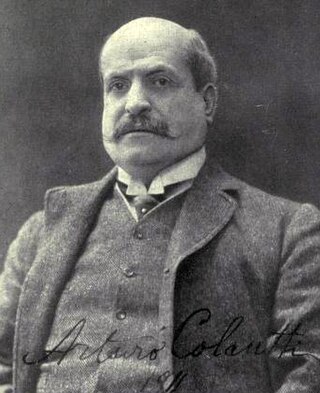

Arturo Colautti was a Dalmatian Italian journalist, polemicist and librettist. He was a strong supporter of Italian irredentism for his native Dalmatia.

The Giorgi or Zorzi were a noble family of the Republic of Venice and the Republic of Ragusa.

Renzo de' Vidovich is a Dalmatian Italian politician, historian and journalist.

In 1918–1920, a series of violent fights took place in the city of Split between Croats and Italians, culminating in a struggle on 11 July 1920 that resulted in the deaths of Captain Tommaso Gulli of the Italian protected cruiser Puglia, Croat civilian Matej Miš, and Italian sailor Aldo Rossi. The incidents were the cause of the destruction in Trieste of the Slovenian Cultural Centre by Italian Fascists.

Italians of Croatia are an autochthonous historical national minority recognized by the Constitution of Croatia. As such, they elect a special representative to the Croatian Parliament. There is the Italian Union of Croatia and Slovenia, which is a Croatian-Slovenian joint organization with its main site in Rijeka, Croatia and its secondary site in Koper, Slovenia.

Italian irredentism in Dalmatia was the political movement supporting the unification to Italy, during the 19th and 20th centuries, of Adriatic Dalmatia.

Giovanni Squarcina was an Italian painter.

Giuliano-Dalmata is the 31st quartiere of Rome, identified by the initials Q. XXXI. Its name refers to the Julian, Istrian and Dalmatian refugees that settled there in the postwar period.

Aldo Duro was a Dalmatian Italian linguist and lexicographer. He worked for both the Accademia della Crusca and the Enciclopedia Italiana, of which he was director of the lexicography. Duro was also the director of the Italian Vocabulary.

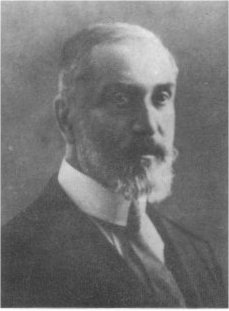

Roberto Ghiglianovich was a Dalmatian Italian politician.

Vincenzo Duplancich was a Dalmatian Italian journalist, writer, politician, and nationalist. He promoted Italian culture and the preservation of Italian identity in Dalmatia, firmly opposing the annexation of the latter to Croatia. He was active during and within the Risorgimento.

Lucio Toth was a Dalmatian Italian politician.

Francesco Carrara was a Dalmatian Italian archaeologist.

Giorgio Politeo was a Dalmatian Italian philosopher and educator. He is said to have elaborated "a form of intuitionism based on Indian mysticism."