Related Research Articles

Ferromagnetism is a property of certain materials that results in a significant, observable magnetic permeability, and in many cases, a significant magnetic coercivity, allowing the material to form a permanent magnet. Ferromagnetic materials are familiar metals that are noticeably attracted to a magnet, a consequence of their substantial magnetic permeability. Magnetic permeability describes the induced magnetization of a material due to the presence of an external magnetic field. This temporarily induced magnetization, for example, inside a steel plate, accounts for its attraction to the permanent magnet. Whether or not that steel plate acquires a permanent magnetization itself depends not only on the strength of the applied field but on the so-called coercivity of the ferromagnetic material, which can vary greatly.

Spintronics, also known as spin electronics, is the study of the intrinsic spin of the electron and its associated magnetic moment, in addition to its fundamental electronic charge, in solid-state devices. The field of spintronics concerns spin-charge coupling in metallic systems; the analogous effects in insulators fall into the field of multiferroics.

In materials that exhibit antiferromagnetism, the magnetic moments of atoms or molecules, usually related to the spins of electrons, align in a regular pattern with neighboring spins pointing in opposite directions. This is, like ferromagnetism and ferrimagnetism, a manifestation of ordered magnetism. The phenomenon of antiferromagnetism was first introduced by Lev Landau in 1933.

In physics and materials science, the Curie temperature (TC), or Curie point, is the temperature above which certain materials lose their permanent magnetic properties, which can be replaced by induced magnetism. The Curie temperature is named after Pierre Curie, who showed that magnetism was lost at a critical temperature.

In electromagnetism, the magnetic susceptibility is a measure of how much a material will become magnetized in an applied magnetic field. It is the ratio of magnetization M to the applied magnetizing field intensity H. This allows a simple classification, into two categories, of most materials' responses to an applied magnetic field: an alignment with the magnetic field, χ > 0, called paramagnetism, or an alignment against the field, χ < 0, called diamagnetism.

Magnetostriction is a property of magnetic materials that causes them to change their shape or dimensions during the process of magnetization. The variation of materials' magnetization due to the applied magnetic field changes the magnetostrictive strain until reaching its saturation value, λ. The effect was first identified in 1842 by James Joule when observing a sample of iron.

Remanence or remanent magnetization or residual magnetism is the magnetization left behind in a ferromagnetic material after an external magnetic field is removed. Colloquially, when a magnet is "magnetized", it has remanence. The remanence of magnetic materials provides the magnetic memory in magnetic storage devices, and is used as a source of information on the past Earth's magnetic field in paleomagnetism. The word remanence is from remanent + -ence, meaning "that which remains".

In physics, a ferromagnetic material is said to have magnetocrystalline anisotropy if it takes more energy to magnetize it in certain directions than in others. These directions are usually related to the principal axes of its crystal lattice. It is a special case of magnetic anisotropy. In other words, the excess energy required to magnetize a specimen in a particular direction over that required to magnetize it along the easy direction is called crystalline anisotropy energy.

Giant magnetoresistance (GMR) is a quantum mechanical magnetoresistance effect observed in multilayers composed of alternating ferromagnetic and non-magnetic conductive layers. The 2007 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Albert Fert and Peter Grünberg for the discovery of GMR.

A ferrite is a ceramic material made by mixing and firing large proportions of iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3, rust) blended with small proportions of one or more additional metallic elements, such as strontium, barium, manganese, nickel, and zinc. They are ferrimagnetic, meaning they can be magnetized or attracted to a magnet. Unlike other ferromagnetic materials, most ferrites are not electrically conductive, making them useful in applications like magnetic cores for transformers to suppress eddy currents. Ferrites can be divided into two families based on their resistance to being demagnetized (magnetic coercivity).

Multiferroics are defined as materials that exhibit more than one of the primary ferroic properties in the same phase:

Exchange bias or exchange anisotropy occurs in bilayers of magnetic materials where the hard magnetization behavior of an antiferromagnetic thin film causes a shift in the soft magnetization curve of a ferromagnetic film. The exchange bias phenomenon is of tremendous utility in magnetic recording, where it is used to pin the state of the readback heads of hard disk drives at exactly their point of maximum sensitivity; hence the term "bias."

Uranium dioxide or uranium(IV) oxide , also known as urania or uranous oxide, is an oxide of uranium, and is a black, radioactive, crystalline powder that naturally occurs in the mineral uraninite. It is used in nuclear fuel rods in nuclear reactors. A mixture of uranium and plutonium dioxides is used as MOX fuel. Prior to 1960, it was used as yellow and black color in ceramic glazes and glass.

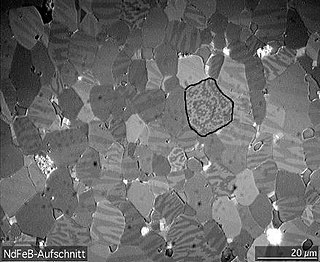

Micromagnetics is a field of physics dealing with the prediction of magnetic behaviors at sub-micrometer length scales. The length scales considered are large enough for the atomic structure of the material to be ignored, yet small enough to resolve magnetic structures such as domain walls or vortices.

Quadratic magnetic rotation is a type of magneto-optic effect, discovered in the mid 1980s by a team of Ukrainian physicists. QMR, like the Faraday effect, establishes a relationship between the magnetic field and rotation of polarization of the plane of linearly polarized light. In contrast to the Faraday effect, QMR originates from the quadratic proportionality between the angle of the rotation of the plane of polarization and the strength of the magnetic field. Mostly QMR can be observed in the transverse geometry when the vector of the magnetic field strength is perpendicular to the direction of light propagation.

A magnetic domain is a region within a magnetic material in which the magnetization is in a uniform direction. This means that the individual magnetic moments of the atoms are aligned with one another and they point in the same direction. When cooled below a temperature called the Curie temperature, the magnetization of a piece of ferromagnetic material spontaneously divides into many small regions called magnetic domains. The magnetization within each domain points in a uniform direction, but the magnetization of different domains may point in different directions. Magnetic domain structure is responsible for the magnetic behavior of ferromagnetic materials like iron, nickel, cobalt and their alloys, and ferrimagnetic materials like ferrite. This includes the formation of permanent magnets and the attraction of ferromagnetic materials to a magnetic field. The regions separating magnetic domains are called domain walls, where the magnetization rotates coherently from the direction in one domain to that in the next domain. The study of magnetic domains is called micromagnetics.

Manganese(II) fluoride is the chemical compound composed of manganese and fluoride with the formula MnF2. It is a light pink solid, the light pink color being characteristic for manganese(II) compounds. It is made by treating manganese and diverse compounds of manganese(II) in hydrofluoric acid. Like some other metal difluorides, MnF2 crystallizes in the rutile structure, which features octahedral Mn centers.

The inverse magnetostrictive effect, magnetoelastic effect or Villari effect, after its discoverer Emilio Villari, is the change of the magnetic susceptibility of a material when subjected to a mechanical stress.

In its most general form, the magnetoelectric effect (ME) denotes any coupling between the magnetic and the electric properties of a material. The first example of such an effect was described by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1888, who found that a dielectric material moving through an electric field would become magnetized. A material where such a coupling is intrinsically present is called a magnetoelectric.

CeCoIn5 ("Cerium-Cobalt-Indium 5") is a heavy-fermion superconductor with a layered crystal structure, with somewhat two-dimensional electronic transport properties. The critical temperature of 2.3 K is the highest among all of the Ce-based heavy-fermion superconductors.

References

- ↑ Cullity, B. D. (1971). "Fundamentals of Magnetostriction". Journal of Metals . 23 (1): 35–41. Bibcode:1971JOM....23a..35C. doi:10.1007/BF03355677.

- ↑ IEEE Standard on Magnetostrictive Materials: Piezomagnetic Nomenclature. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.1991.101048. ISBN 0-7381-4558-0.

- ↑ Dzialoshinskii, I. E. (1958). "The problem of piezomagnetism" (PDF). Soviet Phys. JETP. 6: 621.

- ↑ Borovik-Romanov, A.S. (1960). "Piezomagnetism in the antiferromagnetic fluorides of cobalt and manganese" (PDF). Soviet Phys. JETP. 11: 786.

- ↑ Jaime, M.; Saul, A.; Salamon, M.; Zapf, V. S.; Harrison, N.; Durakiewicz, T.; Lashley, J. C.; Andersson, D. A.; Stanek, C. R.; Smith, J. L.; Gofryk, K. (2017). "Piezomagnetism and magnetoelastic memory in uranium dioxide". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 99. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8...99J. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00096-4. PMC 5524652 . PMID 28740123.