Related Research Articles

The history of Sri Lanka is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and the surrounding regions, comprising the areas of South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. The early human remains found on the island of Sri Lanka date to about 38,000 years ago.

Sinhalese people are an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic group native to the island of Sri Lanka. They were historically known as Hela people. They constitute about 75% of the Sri Lankan population and number more than 16.2 million. The Sinhalese identity is based on language, cultural heritage and nationality. The Sinhalese people speak Sinhala, an insular Indo-Aryan language, and are predominantly Theravada Buddhists, although a minority of Sinhalese follow branches of Christianity and other religions. Since 1815, they were broadly divided into two respective groups: The 'Up-country Sinhalese' in the central mountainous regions, and the 'Low-country Sinhalese' in the coastal regions; although both groups speak the same language, they are distinguished as they observe different cultural customs.

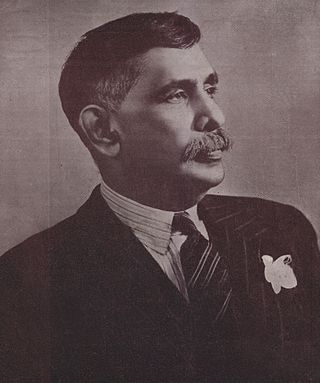

Don Stephen Senanayake was a Ceylonese statesman. He was the first Prime Minister of Ceylon having emerged as the leader of the Sri Lankan independence movement that led to the establishment of self-rule in Ceylon. He is considered as the "Father of the Nation".

Theravada Buddhism is the largest and official religion of Sri Lanka, practiced by 70.2% of the population as of 2012. Practitioners of Sri Lankan Buddhism can be found amongst the majority Sinhalese population as well as among the minority ethnic groups. Sri Lankan Buddhists share many similarities with Southeast Asian Buddhists, specifically Myanmar Buddhists and Thai Buddhists due to traditional and cultural exchange. Sri Lanka is one of five nations with a Theravada Buddhist majority.

Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike, often referred to by his initials as S W R D or S W R D Bandaranaike and known by the Sri Lankan people as "The Silver Bell of Asia", was the fourth Prime Minister of the Dominion of Ceylon, serving from 1956 until his assassination in 1959, causing him to die in office. The founder of the left-wing and Sinhalese nationalist Sri Lanka Freedom Party, his tenure saw the country's first left-wing reforms.

Indian Tamils of Sri Lanka are Tamil people of Indian origin in Sri Lanka. They are also known as Malayaga Tamilar, Hill Country Tamils, Up-Country Tamils or simply Indian Tamils. They predominantly descend from workers sent from Southern India to Sri Lanka in the 19th and 20th centuries to work in coffee, tea and rubber plantations. Some also migrated on their own as merchants and as other service providers. These Tamil speakers mostly live in the central highlands, also known as the Malayakam or Hill Country, yet others are also found in major urban areas and in the Northern Province. A majorty of Hill Country Tamils are predominantly descendants from the lower working castes of South India. Although they are all termed as Tamils today, some have Telugu and Malayalee origins as well as diverse South Indian caste origins. They are instrumental in the plantation sector economy of Sri Lanka. In general, socio-economically their standard of living is below that of the national average and they are described as one of the poorest and most neglected groups in Sri Lanka. In 1964 a large percentage were repatriated to India, but left a considerable number as stateless people. By the 1990s most of these had been given Sri Lankan citizenship. Most are Hindus with a minority of Christians and Muslims amongst them. There are also a small minority followers of Buddhism among them. Politically they are supportive of trade union-based political parties that have supported most of the ruling coalitions since the 1980s.

Samuel James Veluppillai Chelvanayakam was a Ceylonese lawyer, politician and Member of Parliament. He was the founder and leader of the Illankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK) and Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) and a political leader of the Ceylon Tamil community for more than two decades. Chelvanayakam has been described as a father figure to Ceylon's Tamils, to whom he was known as "Thanthai Chelva".

Mudaliyar was a Ceylonese colonial title during Portuguese and British rule of the island. Stemming from the native headman system, the title was usually hereditary, made to wealthy influential families loyal to the British Crown.

The Soulbury Commission, announced in 1944 was, like its predecessor, the Donoughmore Commission, a prime instrument of constitutional reform in British Ceylon. The immediate basis for the appointment of a commission for constitutional reforms was the 1944 draft constitution of the Board of Ministers, headed by D.S. Senanayake. This commission ushered in Dominion status and Independence to Sri Lanka in 1948. Its constitutional recommendations were largely those of the 1944 Board of Ministers' draft, a document reflecting the influence of Senanayake and his main advisor, Sir Ivor Jennings.

Walauwa or walawwa is the name given to a feudal/colonial manor house in Sri Lanka of a native headmen. It also refers to the feudal social systems that existed during the colonial era.

Subaiya Natesan was a Ceylonese politician, Member of State Council, Member of Parliament and senator.

The British Ceylon period is the history of Sri Lanka between 1815 and 1948. It follows the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom into the hands of the British Empire. It ended over 2300 years of Sinhalese monarchy rule on the island. The British rule on the island lasted until 1948 when the country regained independence following the Sri Lankan independence movement.

Rajamanthri Walauwa or manor house of Rajamanthri is situated in Karandagolla, Hanguranketha, Sri Lanka. Rajamanthri Walauwa is an eight-room, 200-year-old mansion built by the last Chief Minister of the Kingdom of Kandy in 1804. It was fully restored in 1944. In 1970, Prince Gamini Rajamanthri and in 1972, Prince Samantha Rajamanthri, Julius Rajamanthri's two sons became the new inhabitants of the Rajamanthri Walauwa. To this day, the manor house is managed by Prince Julius' sons.

Kalpitiya Fort was built by the Dutch between 1667 and 1676. Kalpitiya was important as it commands the entrance to the adjacent bay, Puttalam Lagoon. The surrounding Puttalam area was one of the major cinnamon cultivation areas in Sri Lanka. The Dutch even constructed a canal from Puttalam via Negombo to Colombo to transport cinnamon from the area.

Dodanthale Raja Maha Vihara is an historic Buddhist temple situated in Mawanella, Kegalle District, Sri Lanka. The temple is located about 4 km (2.5 mi) away from the Mawanella town. The temple has been formally recognised by the Government as an archaeological site in Sri Lanka. The designation was declared on 10 November 1978 under the government Gazette number 10.

In Sri Lankan architecture a Maha Gabadava is a type of large granary in the form of a separate building from the main compound. In the Kandyan period the Sinhalese kings would send daily provisions from the Maha Gabadava to the two main monastic orders, the Malwathu Maha Viharaya and Asgiri Maha Viharaya. This was continued after the fall of the Kingdom of Kandy.

Pekada, or pekadaya, are the decorative wooden pillar heads/brackets at the top of a stone or wooden column, known as kapa, supporting a beam or dandu. It is a unique feature of Kandyan architecture.

Kala Suri Barbara Sansoni was a Sri Lankan designer, artist, colourist, entrepreneur, and writer. She was known for her works in architecture, textile designs, and handwoven panels. She founded the Barefoot textile company, a company that is highly acclaimed for its handloom fabric. She also served as the chairperson and chief designer of Barefoot Pvt. Ltd for several years.

References

- 1 2 3 Lewcock, Sonsoni & Senanayake 2014, p. 23.

- ↑ Coomaraswamy 2011, p. 199.

- 1 2 Lewcock, Sonsoni & Senanayake 2014, p. 21.