Poisonous amphibians are amphibians that produce toxins to defend themselves from predators.

Poisonous amphibians are amphibians that produce toxins to defend themselves from predators.

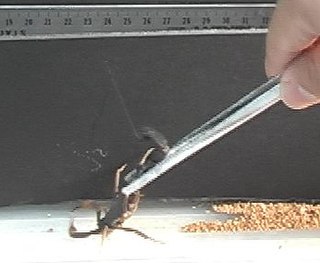

Most toxic amphibians are poisonous to touch or eat. These amphibians usually sequester toxins from animals and plants on which they feed, commonly from poisonous insects or poisonous plants. Except certain salamandrid salamanders that can extrude sharp venom-tipped ribs, [1] [2] and two species of frogs with venom-tipped bone spurs on their skulls, amphibians are not known to actively inject venom.

An example of poison ingestion derives from the poison dart frog. They get a deadly chemical called lipophilic alkaloid from consuming a poisonous food in the rainforest. They are immune to the poison and they secrete it through their skin as a defense mechanism against predators. This poison is so efficient, the native people of the South American Amazon rainforest use the frogs' toxins on their weapons to kill their prey, giving the frogs their nickname the "poison dart frog".

| Image | Scientific name | Active agent | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dendrobatidae Poison Dart Frogs | lipophilic alkaloid toxins: allopumiliotoxin 267A, batrachotoxin, epibatidine, histrionicotoxin, pumiliotoxin 251D | humid, tropical environments of Central and South America |

| Mantella genus Golden frogs or Malagasy poison frogs | alkaloid toxins | Madagascar |

| northern corroboree frog ( Pseudophryne pengilleyi ) | pseudo-phrynamine | Southern Tablelands of Australia. | |

| southern corroboree frog ( Pseudophryne corroboree ) | pseudo-phrynamine | Southern Tablelands of Australia. |

| Bruno's casque-headed frog (Aparasphenodon brunoi) | Unknown injectable venom [3] | Brazil |

| Greening's frog (Corythomantis greeningi) | Unknown injectable venom [3] | Brazil | |

| Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus zeteki) | Zetekitoxin AB, Bufadienolide | Central Panama. |

| American toad (Anaxyrus americanus) | Bufotoxin | eastern United States and Canada. |

| Colorado River toad (Incilius alvarius) | 5-MeO-DMT, Bufotenin | southeastern California, New Mexico, Mexico and much of southern Arizona |

| Rhinella arenarum | Bufotoxin | Argentina from the Chubut Province northward, Bolivia east of the Andes, southern Brazil, and Uruguay |

| Asian giant toad ( Phrynoidis asper ) | Bufotoxin | Mainland Southeast Asia and the Greater Sundas. |

| Colombian giant toad, Blomberg's toad (Rhaebo blombergi) | Bufotoxin | western Colombia (Chocó, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, and Nariño Departments) and northwestern Ecuador (Carchi, Esmeraldas, and Imbabura Provinces) | |

| western toad (Anaxyrus boreas) | Bufotoxin | western British Columbia and southern Alaska south through Washington, Oregon, and Idaho to northern Baja California, Mexico; east to Montana, western and central Wyoming, Nevada, the mountains and higher plateaus of Utah, and western Colorado. |

| common toad, European toad Bufo bufo | bufotalin, bufalitoxin and bufotoxin | Europe |

| Asiatic toad or Chusan Island toad (Bufo gargarizans) | Bufotoxin | East Asia. |

| African common toad or guttural toad (Sclerophrys gutturalis) | Bufotoxin | Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Réunion, Somalia, South Africa, Ethiopia, Eswatini, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. |

| Japanese common toad, Japanese warty toad or Japanese toad (Bufo japonicus) | bufotalin, Bufotoxin | Japan and is present on the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu and Shikoku |

| Fowler's toad (Anaxyrus fowleri) | Bufotoxin | eastern United States and parts of adjacent Canada |

| cane toad (Rhinella marina) | Bufotoxin, Bufotenin | Rio Grande Valley in South Texas to the central Amazon and southeastern Peru, and some of the continental islands near Venezuela (such as Trinidad and Tobago) Introduced in Australia, Florida and Hawaii, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, the Ogasawara, Ishigaki Island and the Daitō Islands of Japan, most Caribbean islands, Fiji and many other Pacific islands |

| Asian common toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus) | Bufotoxin | South and Southeast Asia. |

| Peltophryne peltocephala | Bufotoxin | Cuba |

| oak toad (Anaxyrus quercicus) | Bufotoxin | southeastern United States. |

| African common toad, square-marked toad, African toad (Sclerophrys regularis) | Bufotoxin | Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ivory Coast, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Uganda. |

| Gulf Coast toad (Incilius valliceps) | Bufotoxin | eastern and southeastern Mexico and Central America as far south as Costa Rica. |

| European green toad (Bufotes viridis) | Bufotoxin | mainland Europe, ranging from far eastern France and Denmark to the Balkans and Western Russia. |

| Image | Scientific name | Active agent | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taricha genus Western Newt | Tetrodotoxin | Pacific coastal region from southern Alaska to southern California, and Mexico |

| Triturus genus crested and the marbled newts | Tetrodotoxin | Great Britain through most of continental Europe to westernmost Siberia, Anatolia, and the Caspian Sea region |

| Notophthalmus genus | Tetrodotoxin [4] | eastern United States, Mexico |

| Salamandra genus | samandarin, samandarone, O-acetylsamandarine [5] | southern and central Europe |

| Iberian ribbed newt (Pleurodeles waltl) | Unknown [6] | central and southern Iberian Peninsula and Morocco. |

Some people use the bufotoxins of some species of toxic toads as a drug to get high, but this can become very dangerous. Usually due to the toads' size and toxicity, the poisons would not be deadly to a fully grown, healthy adult. But if too much of the toxin is absorbed, or if the person is young or ill, then the poisons can become a serious threat. It also depends on species: some amphibians do have toxins strong enough to kill even a healthy mature person within just a few minutes, while other species may not have toxins potent enough to have any effect. Licking toads is not biologically practical. For these tryptamines to be orally activated, the human monoamine oxidase system must be inhibited. Therefore, licking a poisonous amphibian will not guarantee a sufficient dose.

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniotic, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all tetrapods excluding the amniotes. All extant (living) amphibians belong to the monophyletic subclass Lissamphibia, with three living orders: Anura, Urodela (salamanders), and Gymnophiona (caecilians). Evolved to be mostly semiaquatic, amphibians have adapted to inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living in freshwater, wetland or terrestrial ecosystems. Their life cycle typically starts out as aquatic larvae with gills known as tadpoles, but some species have developed behavioural adaptations to bypass this.

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved venom apparatus, such as fangs or a stinger, in a process called envenomation. Venom is often distinguished from poison, which is a toxin that is passively delivered by being ingested, inhaled, or absorbed through the skin, and toxungen, which is actively transferred to the external surface of another animal via a physical delivery mechanism.

Garter snake is the common name for small to medium-sized snakes belonging to the genus Thamnophis in the family Colubridae. They are native to North and Central America, ranging from central Canada in the north to Costa Rica in the south.

The common garter snake is a species of snake in the subfamily Natricinae of the family Colubridae. The species is indigenous to North America and found widely across the continent. There are several recognized subspecies. Most common garter snakes have a pattern of yellow stripes on a black, brown or green background, and their average total length is about 55 cm (22 in), with a maximum total length of about 137 cm (54 in). The average body mass is 150 g (5.3 oz). The common garter snake is the state reptile of Massachusetts.

Poison dart frog is the common name of a group of frogs in the family Dendrobatidae which are native to tropical Central and South America. These species are diurnal and often have brightly colored bodies. This bright coloration is correlated with the toxicity of the species, making them aposematic. Some species of the family Dendrobatidae exhibit extremely bright coloration along with high toxicity — a feature derived from their diet of ants, mites and termites— while species which eat a much larger variety of prey have cryptic coloration with minimal to no amount of observed toxicity. Many species of this family are threatened due to human infrastructure encroaching on their habitats.

Batrachotoxin (BTX) is an extremely potent cardiotoxic and neurotoxic steroidal alkaloid found in certain species of beetles, birds, and frogs. The name is from the Greek word βάτραχος, bátrachos, 'frog'. Structurally-related chemical compounds are often referred to collectively as batrachotoxins. In certain frogs, this alkaloid is present mostly on the skin. Such frogs are among those used for poisoning darts. Batrachotoxin binds to and irreversibly opens the sodium channels of nerve cells and prevents them from closing, resulting in paralysis and death. No antidote is known.

In evolutionary biology, an evolutionary arms race is an ongoing struggle between competing sets of co-evolving genes, phenotypic and behavioral traits that develop escalating adaptations and counter-adaptations against each other, resembling the geopolitical concept of an arms race. These are often described as examples of positive feedback. The co-evolving gene sets may be in different species, as in an evolutionary arms race between a predator species and its prey, or a parasite and its host. Alternatively, the arms race may be between members of the same species, as in the manipulation/sales resistance model of communication or as in runaway evolution or Red Queen effects. One example of an evolutionary arms race is in sexual conflict between the sexes, often described with the term Fisherian runaway. Thierry Lodé emphasized the role of such antagonistic interactions in evolution leading to character displacements and antagonistic coevolution.

Venomous mammals are tetrapods of the class Mammalia that produce venom, which they use to kill or disable prey, to defend themselves from predators or conspecifics or in agonistic encounters. Mammalian venoms form a heterogeneous group with different compositions and modes of action, from four orders of mammals: Eulipotyphla, Monotremata, Primates, and Chiroptera. To explain the rarity of venom delivery in Mammalia, Mark Dufton of the University of Strathclyde has suggested that modern mammalian predators do not need venom because they are able to kill quickly with their teeth or claws, whereas venom, no matter how sophisticated, requires time to disable prey.

The rough-skinned newt or roughskin newt is a North American newt known for the strong toxin exuded from its skin.

The California newt or orange-bellied newt, is a species of newt endemic to California, in the Western United States. Its adult length can range from 5 to 8 in. Its skin produces the potent toxin tetrodotoxin.

Venomous snakes are species of the suborder Serpentes that are capable of producing venom, which they use for killing prey, for defense, and to assist with digestion of their prey. The venom is typically delivered by injection using hollow or grooved fangs, although some venomous snakes lack well-developed fangs. Common venomous snakes include the families Elapidae, Viperidae, Atractaspididae, and some of the Colubridae. The toxicity of venom is mainly indicated by murine LD50, while multiple factors are considered to judge the potential danger to humans. Other important factors for risk assessment include the likelihood that a snake will bite, the quantity of venom delivered with the bite, the efficiency of the delivery mechanism, and the location of a bite on the body of the victim. Snake venom may have both neurotoxic and hemotoxic properties. There are about 600 venomous snake species in the world.

The golden poison frog, also known as the golden dart frog or golden poison arrow frog, is a poison dart frog endemic from the rainforests of Colombia. The golden poison frog has become endangered due to habitat destruction within its naturally limited range. Despite its small size, this frog is considered to be the most poisonous extant animal species on the planet.

Phyllobates bicolor, or more commonly referred to as the black-legged poison dart frog, is the world's second-most toxic dart frog. Under the genus Phyllobates, this organism is often mistaken as Phyllobates terribilis, the golden poison frog, as both are morphologically similar. However, Phyllobatesbicolor is identifiable by the yellow or orange body and black or dark blue forelimbs and hindlegs, hence the name black-legged dart frog. Phyllobates bicolor are commonly found in tropical forests of the Chocó region of Colombia. The diurnal frogs live along the rainforest ground near streams or puddles that form. Notably, P. bicolor is a member of the family Dendrobatidae, or poison dart frog. P. bicolor, along with the rest of the Phyllobates species, produce a neurotoxin known as a batrachotoxin that inhibits specific transmembrane channels in cells. Due to this highly deadly toxin that the frogs secrete, many indigenous groups of the Colombian rainforest have extracted the toxins to create poison tipped darts used for hunting. During the breeding period, P. bicolor emits high pitched single notes as a mating call. As in all poison dart frogs, it is common for the father of tadpoles to carry the offspring on his back until they reach a suitable location for the tadpoles to develop. P. bicolor is an endangered species according to the IUCN red list. Currently, deforestation, habitat loss, and pollution pose the biggest threat to the species. Limited conservation efforts have been attempted to prevent further damage to the species. Despite this, there are still institutions such as the Baltimore National Aquarium in Baltimore, Maryland and the Tatamá National Natural Park in Colombia that are engaged in P. bicolor conservation efforts such as captive breeding.

The Sierra newt is a newt found west of the Sierra Nevada, from Shasta county to Tulare County, in California, Western North America.

Unkenreflex – interchangeably referred to as unken reflex – is a defensive posture adopted by several branches of the amphibian class – including salamanders, toads, and certain species of frogs. Implemented most often in the face of an imminent attack by a predator, unkenreflex is characterized by the subject’s contortion or arching of its body to reveal previously hidden bright colors of the ventral side, tail, or inner limb; the subject remains immobile while in unkenreflex.

Toxic birds are birds that use toxins to defend themselves from predators. Although no known bird actively injects or produces venom, toxic birds sequester poison from animals and plants they consume, especially poisonous insects. Species include the pitohui and ifrita birds from Papua New Guinea, the European quail, the spur-winged goose, hoopoes, the bronzewing pigeon, and the red warbler.

The red-backed poison frog is a species of frog in the family Dendrobatidae. It is an arboreal insectivorous species, and is the second-most poisonous species in the genus, after R. variabilis. Like many species of small, poisonous frogs native to South America, it is grouped with the poison dart frogs, and is a moderately toxic species, containing poison capable of causing serious injury to humans, and death in animals such as chickens. R. reticulata is native to the Amazon rainforest in Peru and Ecuador.

A toxungen comprises a secretion or other bodily fluid containing one or more biological toxins that is transferred by one animal to the external surface of another animal via a physical delivery mechanism but without direct contact between the secreting animal and the victim. Toxungens can be delivered through spitting, spraying, or smearing. As one of three categories of biological toxins, toxungens can be distinguished from poisons, which are passively transferred via ingestion, inhalation, or absorption across the skin, and venoms, which are delivered through a wound generated by direct contact in the form of a bite, sting, or other such action. Toxungen use offers the evolutionary advantage of delivering toxins into the target's tissues without the need for physical contact. Animals that deploy toxungens are referred to as toxungenous.