Application

Current thresholds

The presumption of supply thresholds are set out in Schedule 5 of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975. As of December 2016 [update] , the thresholds are as follows: [14]

| Amount | Applicable drugs |

|---|---|

| 2.5 milligrams | Lysergide (LSD) |

| 25 milligrams | 25B-NBOMe 25C-NBOMe 25I-NBOMe |

| 100 milligrams | DOB (bromo-DMA) |

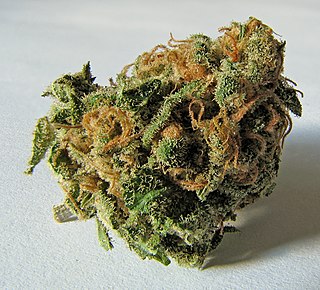

| 250 milligrams | Tetrahydrocannabinol |

| 0.5 grams | Cocaine Heroin |

| 5 grams | Amphetamine Morphine MDMA MDA Cannabis preparations BZP TFMPP pFPP MeOPP mCPP MBZP Methamphetamine |

| 10 grams | Ketamine Ephedrine Pseudoephedrine |

| 28 grams | Cannabis plant |

| 56 grams | all other controlled drugs |

Bill of Rights Act 1990

The New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 sets out the rights and freedoms of anyone subject to New Zealand law, and is part of the country's uncodified constitution. The act protects fundamental rights and freedoms in New Zealand society in a general, rather than absolute, sense. [15] When an act is prima facie inconsistent with a right or freedom contained in the Bill of Rights, the starting point for that act's application is to examine that meaning against the guaranteed right to see if the right is curtailed. If so, the Bill of Rights' interpretive provisions (sections 4, 5 and 6) are engaged.

Presumption of innocence: Section 25(c)

Section 25(c) of the Bill of Rights Act 1990 affirms the right of anyone charged with an offence to be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law. [11] It establishes that the burden of proof of guilt in criminal cases is carried by the prosecutor, who must prove the accused's guilt beyond reasonable doubt. It is widely-acknowledged common law that the prosecution must prove guilt even when an affirmative defence is argued. [16] A provision requiring an accused person to disprove the existence of a presumed fact, that fact being an important element of the offence in question (e.g. the presumption of supply) generally violates the presumption of innocence in section 25(c). [17]

Section 4

This section does not cite any sources .(November 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Section 4 specifies that the Bill of Rights Act is not supreme law. It provides that courts hearing cases under the act cannot repeal or revoke, make invalid or ineffective, or decline to apply any provision of any statute made by Parliament because it is inconsistent with any provision in the Bill of Rights Act. This is the case whether the statute was passed before or after the Bill of Rights Act. Another statute will prevail if it is inconsistent with the Bill of Rights Act and cannot be said to be a justified limitation under section 5 or interpreted consistently with the Bill of Rights Act under section 6.

Section 5

Section 5 provides that if legislation is found to be prima facie inconsistent with a particular right or freedom, it may be consistent with the Bill of Rights Act if the inconsistency is a justified limitation. The application of section 5 is two-fold; the courts must look at whether the provision serves an important and significant objective, and if there is a rational and proportionate connection between that objective and the provision. [13]

Case law in overseas jurisdictions suggests that restricting the supply of illicit drugs is a pressing social objective which might, in certain circumstances, justify limitations on the presumption of innocence. [17] [18] This was accepted in New Zealand by the Supreme Court in the leading case of R v Hansen; [2] however, a majority of the court found that the reverse onus of the presumption of supply contained in section 6(6) of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 [19] was unconnected to the objective or a disproportionate response to the problem. [13]

Section 6

Section 6 states that where an act can be given a meaning consistent with the rights and freedoms contained in the Bill of Rights, that meaning shall be preferred to any other; [20] this was the basis of the appeal in R v Hansen.

R v Hansen (2007)

The leading New Zealand case on the presumption of supply is R v Hansen, where the appellant was charged with possession of cannabis for the purpose of supply. [2] Hansen argued that being required to persuade a jury that he did not possess cannabis for the purpose of sale or supply was inconsistent with his right under section 25(c) of the Bill of Rights Act 1990, the presumption of innocence until proven guilty. He argued that section 6 of the Bill of Rights Act required section 6(6) of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 to be given a meaning consistent with the presumption of innocence. [21]

Hansen contended that consistency with the presumption of innocence would be achieved if section 6(6) of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 was construed to impose an evidential burden on him which, if accepted by the jury, might create a reasonable doubt of his possession being for supply. This would impose the legal onus on the Crown to satisfy the jury beyond reasonable doubt that the appellant was in possession of drugs for supply. [22]

The majority of the court found that the reverse onus in section 6(6) of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 was not rationally connected to the objective or it was not a proportionate response to the problem, and was in breach of section 25(c) of the Bill of Rights Act 1990. However, section 4 of the Bill of Rights Act forced the court to allow the presumption-of-supply clause to prevail, and Hansen's appeal was unsuccessful.