Privacy is the ability of an individual or group to seclude themselves or information about themselves, and thereby express themselves selectively.

The right to privacy is an element of various legal traditions that intends to restrain governmental and private actions that threaten the privacy of individuals. Over 150 national constitutions mention the right to privacy. On 10 December 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), originally written to guarantee individual rights of everyone everywhere; while right to privacy does not appear in the document, many interpret this through Article 12, which states: "No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks."

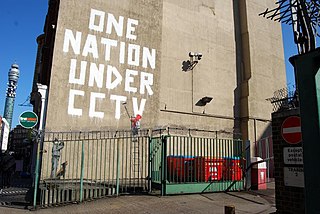

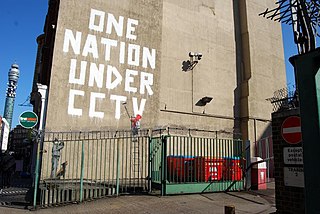

Mass surveillance is the intricate surveillance of an entire or a substantial fraction of a population in order to monitor that group of citizens. The surveillance is often carried out by local and federal governments or governmental organizations, such as organizations like the NSA, but it may also be carried out by corporations. Depending on each nation's laws and judicial systems, the legality of and the permission required to engage in mass surveillance varies. It is the single most indicative distinguishing trait of totalitarian regimes. It is also often distinguished from targeted surveillance.

Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT) is a Washington, D.C.–based 501(c)(3) nonprofit organisation that advocates for digital rights and freedom of expression. CDT seeks to promote legislation that enables individuals to use the internet for purposes of well-intent, while at the same time reducing its potential for harm. It advocates for transparency, accountability, and limiting the collection of personal information.

Lawful interception (LI) refers to the facilities in telecommunications and telephone networks that allow law enforcement agencies with court orders or other legal authorization to selectively wiretap individual subscribers. Most countries require licensed telecommunications operators to provide their networks with Legal Interception gateways and nodes for the interception of communications. The interfaces of these gateways have been standardized by telecommunication standardization organizations. As with many law enforcement tools, LI systems may be subverted for illicit purposes.

Data retention defines the policies of persistent data and records management for meeting legal and business data archival requirements. Although sometimes interchangeable, it is not to be confused with the Data Protection Act 1998.

The Native Title Act 1993(Cth) is a law passed by the Australian Parliament, the purpose of which is "to provide a national system for the recognition and protection of native title and for its co-existence with the national land management system". The Act was passed by the Keating government following the High Court's decision in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992). The Act commenced operation on 1 January 1994.

The Privacy Act 1988 is an Australian law dealing with privacy. Section 14 of the Act stipulates a number of privacy rights known as the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs). These principles apply to Australian Government and Australian Capital Territory agencies or private sector organizations contracted to these governments, organizations and small businesses who provide a health service, as well as to private organisations with an annual turnover exceeding AUD$3M. The principles govern when and how personal information can be collected by these entities. Information can only be collected if it is relevant to the agencies' functions. Upon this collection, that law mandates that Australians have the right to know why information about them is being acquired and who will see the information. Those in charge of storing the information have obligations to ensure such information is neither lost nor exploited. An Australian will also have the right to access the information unless this is specifically prohibited by law.

Privacy law is the body of law that deals with the regulating, storing, and using of personally identifiable information, personal healthcare information, and financial information of individuals, which can be collected by governments, public or private organisations, or other individuals. It also applies in the commercial sector to things like trade secrets and the liability that directors, officers, and employees have when handling sensitive information.

Telephone call recording laws are legislation enacted in many jurisdictions, such as countries, states, provinces, that regulate the practice of telephone call recording. Call recording or monitoring is permitted or restricted with various levels of privacy protection, law enforcement requirements, anti-fraud measures, or individual party consent.

Source protection, sometimes also referred to as source confidentiality or in the U.S. as the reporter's privilege, is a right accorded to journalists under the laws of many countries, as well as under international law. It prohibits authorities, including the courts, from compelling a journalist to reveal the identity of an anonymous source for a story. The right is based on a recognition that without a strong guarantee of anonymity, many would be deterred from coming forward and sharing information of public interests with journalists.

The Freedom of Information Act 1982(Cth) is an Act of the Parliament of Australia which guarantees freedom of information (FOI) and the rights of access to official documents of the Commonwealth Government and of its agencies to members of the public. It was passed by the Australian Parliament on 9 March 1982, and commenced on 1 December 1982.

The use of electronic surveillance by the United Kingdom grew from the development of signal intelligence and pioneering code breaking during World War II. In the post-war period, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) was formed and participated in programmes such as the Five Eyes collaboration of English-speaking nations. This focused on intercepting electronic communications, with substantial increases in surveillance capabilities over time. A series of media reports in 2013 revealed bulk collection and surveillance capabilities, including collection and sharing collaborations between GCHQ and the United States' National Security Agency. These were commonly described by the media and civil liberties groups as mass surveillance. Similar capabilities exist in other countries, including western European countries.

The USA Freedom Act is a U.S. law enacted on June 2, 2015, that restored and modified several provisions of the Patriot Act, which had expired the day before. The act imposes some new limits on the bulk collection of telecommunication metadata on U.S. citizens by American intelligence agencies, including the National Security Agency. It also restores authorization for roving wiretaps and tracking lone wolf terrorists. The title of the act is a ten-letter backronym that stands for Uniting and Strengthening America by Fulfilling Rights and Ensuring Effective Discipline Over Monitoring Act of 2015.

Mass surveillance in Australia takes place in several network media, including telephone, internet, and other communications networks, financial systems, vehicle and transit networks, international travel, utilities, and government schemes and services including those asking citizens to report on themselves or other citizens.

The Telecommunications Act 1979 is an Act of the Parliament of Australia which prohibits the unauthorised interception of communications or access to stored communications, with certain exceptions. The Act was amended by the Telecommunications Amendment Act 2015.

The Telecommunications Act 1997 is an act of law in the Commonwealth of Australia.

The Surveillance Devices Act 2007 (NSW) (“the Act”) is a piece of privacy legislation enacted by the Parliament of New South Wales the most populous state in Australia. It replaced the Listening Devices Act 1984 (NSW). The Act makes it an offence to record private conversations apart from in specific and defined circumstances. It makes provision for law enforcement officers to apply for warrants authorising the use of such devices and the circumstances in which judges of the Supreme Court of New South Wales might issue such warrants.

The Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Amendment (Data Retention) Act 2015(Cth) is an Act of the Parliament of Australia that amends the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 (original Act) and the Telecommunications Act 1997 to introduce a statutory obligation for Australian telecommunication service providers (TSPs) to retain, for a period of two years, particular types of telecommunications data (metadata) and introduces certain reforms to the regimes applying to the access of stored communications and telecommunications data under the original Act.

The Investigatory Powers Act 2016 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which received royal assent on 29 November 2016. Its different parts came into force on various dates from 30 December 2016. The Act comprehensively sets out and in limited respects expands the electronic surveillance powers of the British intelligence agencies and police. It also claims to improve the safeguards on the exercise of those powers.