Monopolistic competition is a type of imperfect competition such that there are many producers competing against each other but selling products that are differentiated from one another and hence not perfect substitutes. In monopolistic competition, a company takes the prices charged by its rivals as given and ignores the impact of its own prices on the prices of other companies. If this happens in the presence of a coercive government, monopolistic competition will fall into government-granted monopoly. Unlike perfect competition, the company maintains spare capacity. Models of monopolistic competition are often used to model industries. Textbook examples of industries with market structures similar to monopolistic competition include restaurants, cereals, clothing, shoes, and service industries in large cities. The "founding father" of the theory of monopolistic competition is Edward Hastings Chamberlin, who wrote a pioneering book on the subject, Theory of Monopolistic Competition (1933). Joan Robinson's book The Economics of Imperfect Competition presents a comparable theme of distinguishing perfect from imperfect competition. Further work on monopolistic competition was undertaken by Dixit and Stiglitz who created the Dixit-Stiglitz model which has proved applicable used in the sub fields of international trade theory, macroeconomics and economic geography.

In economics, imperfect competition refers to a situation where the characteristics of an economic market do not fulfil all the necessary conditions of a perfectly competitive market. Imperfect competition causes market inefficiencies, resulting in market failure. Imperfect competition usually describes behaviour of suppliers in a market, such that the level of competition between sellers is below the level of competition in perfectly competitive market conditions.

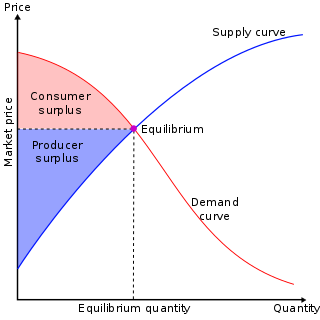

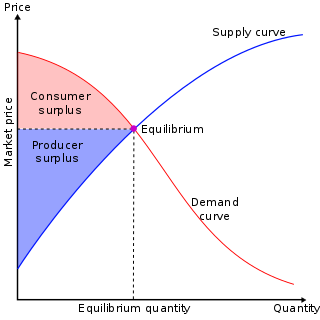

In mainstream economics, economic surplus, also known as total welfare or total social welfare or Marshallian surplus, is either of two related quantities:

To counterfeit means to imitate something authentic, with the intent to steal, destroy, or replace the original, for use in illegal transactions, or otherwise to deceive individuals into believing that the fake is of equal or greater value than the real product. Counterfeit products are fakes or unauthorized replicas of the real product. Counterfeit products are often produced with the intent to take advantage of the superior value of the imitated product. The word counterfeit frequently describes both the forgeries of currency and documents as well as the imitations of items such as clothing, handbags, shoes, pharmaceuticals, automobile parts, unapproved aircraft parts, watches, electronics and electronic parts, software, works of art, toys, and movies.

In marketing jargon, product lining refers to the offering of several related products for individual sale. Unlike product bundling, where several products are combined into one group, which is then offered for sale as a units, product lining involves offering the products for sale separately. A line can comprise related products of various sizes, types, colors, qualities, or prices. Line depth refers to the number of subcategories under a category. Line consistency refers to how closely related the products that make up the line are. Line vulnerability refers to the percentage of sales or profits that are derived from only a few products in the line.

Pricing is the process whereby a business sets the price at which it will sell its products and services, and may be part of the business's marketing plan. In setting prices, the business will take into account the price at which it could acquire the goods, the manufacturing cost, the marketplace, competition, market condition, brand, and quality of product.

Brand equity, in marketing, is the worth of a brand in and of itself – i.e., the social value of a well-known brand name. The owner of a well-known brand name can generate more revenue simply from brand recognition, as consumers perceive the products of well-known brands as better than those of lesser-known brands.

In marketing, brand management begins with an analysis on how a brand is currently perceived in the market, proceeds to planning how the brand should be perceived if it is to achieve its objectives and continues with ensuring that the brand is perceived as planned and secures its objectives. Developing a good relationship with target markets is essential for brand management. Tangible elements of brand management include the product itself; its look, price, and packaging, etc. The intangible elements are the experiences that the target markets share with the brand, and also the relationships they have with the brand. A brand manager would oversee all aspects of the consumer's brand association as well as relationships with members of the supply chain.

In economics, inferior goods are those goods the demand for which falls with increase in income of the consumer. So, there is an inverse relationship between income of the consumer and the demand for inferior goods. There are many examples of inferior goods, including cheap cars, public transit options, payday lending, and inexpensive food. The shift in consumer demand for an inferior good can be explained by two natural economic phenomena: the substitution effect and the income effect.

In microeconomics, substitute goods are two goods that can be used for the same purpose by consumers. That is, a consumer perceives both goods as similar or comparable, so that having more of one good causes the consumer to desire less of the other good. Contrary to complementary goods and independent goods, substitute goods may replace each other in use due to changing economic conditions. An example of substitute goods is Coca-Cola and Pepsi; the interchangeable aspect of these goods is due to the similarity of the purpose they serve, i.e. fulfilling customers' desire for a soft drink. These types of substitutes can be referred to as close substitutes.

In microeconomics, the law of demand is a fundamental principle which states that there is an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. In other words, "conditional on all else being equal, as the price of a good increases (↑), quantity demanded will decrease (↓); conversely, as the price of a good decreases (↓), quantity demanded will increase (↑)". Alfred Marshall worded this as: "When we say that a person's demand for anything increases, we mean that he will buy more of it than he would before at the same price, and that he will buy as much of it as before at a higher price". The law of demand, however, only makes a qualitative statement in the sense that it describes the direction of change in the amount of quantity demanded but not the magnitude of change.

In economics, a luxury good is a good for which demand increases more than what is proportional as income rises, so that expenditures on the good become a more significant proportion of overall spending. Luxury goods are in contrast to necessity goods, where demand increases proportionally less than income. Luxury goods is often used synonymously with superior goods.

A business can use a variety of pricing strategies when selling a product or service. To determine the most effective pricing strategy for a company, senior executives need to first identify the company's pricing position, pricing segment, pricing capability and their competitive pricing reaction strategy. Pricing strategies and tactics vary from company to company, and also differ across countries, cultures, industries and over time, with the maturing of industries and markets and changes in wider economic conditions.

In economics, demand is the quantity of a good that consumers are willing and able to purchase at various prices during a given time. In economics "demand" for a commodity is not the same thing as "desire" for it. It refers to both the desire to purchase and the ability to pay for a commodity.

Brand extension or brand stretching is a marketing strategy in which a firm marketing a product with a well-developed image uses the same brand name in a different product category. The new product is called a spin-off.

The six forces model is an analysis model used to give a holistic assessment of any given industry and identify the structural underlining drivers of profitability and competition. The model is an extension of the Porter's five forces model proposed by Michael Porter in his 1979 article published in the Harvard Business Review "How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy". The sixth force was proposed in the mid-1990s. The model provides a framework of six key forces that should be considered when defining corporate strategy to determine the overall attractiveness of an industry.

A marketing channel consists of the people, organizations, and activities necessary to transfer the ownership of goods from the point of production to the point of consumption. It is the way products get to the end-user, the consumer; and is also known as a distribution channel. A marketing channel is a useful tool for management, and is crucial to creating an effective and well-planned marketing strategy.

A brand is a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that distinguishes one seller's good or service from those of other sellers. Brands are used in business, marketing, and advertising for recognition and, importantly, to create and store value as brand equity for the object identified, to the benefit of the brand's customers, its owners and shareholders. Brand names are sometimes distinguished from generic or store brands.

Customer cost refers not only to the price of a product, but it also encompasses the purchase costs, use costs and the post-use costs. Purchase costs consist of the cost of searching for a product, gathering information about the product and the cost of obtaining that information. Usually, the highest use costs arise for durable goods that have a high demand on resources, such as energy or water, or those with high maintenance costs. Post-use costs encompass the costs for collecting, storing and disposing of the product once the item has been discarded.

Massification is a strategy that some luxury companies use to expose their brands to a broader market and increase sales. As a method of implementing massification, companies have created diffusion lines. Diffusion lines are an offshoot of a company or a designer's original line that is less expensive in order to reach a broader market and gain a wider consumer base. Another strategy used in massification is brand extensions, which is when an already established company releases a new product under their name.