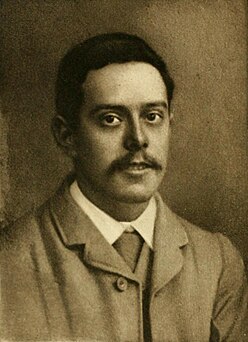

Edgar Allan Poe was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is widely regarded as a central figure of Romanticism in the United States, and of American literature. Poe was one of the country's earliest practitioners of the short story, and considered to be the inventor of the detective fiction genre, as well as a significant contributor to the emerging genre of science fiction. Poe was the first well-known American writer to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career.

The Metamorphoses is an 8 AD Latin narrative poem by the Roman poet Ovid, considered his magnum opus. Comprising 11,995 lines, 15 books and over 250 myths, the poem chronicles the history of the world from its creation to the deification of Julius Caesar within a loose mythico-historical framework.

John Nichols was an English printer, author and antiquary. He is remembered as an influential editor of the Gentleman's Magazine for nearly 40 years; author of a monumental county history of Leicestershire; author of two compendia of biographical material relating to his literary contemporaries; and as one of the agents behind the first complete publication of Domesday Book in 1783.

Cyclopædia: or, An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences is an encyclopedia prepared by Ephraim Chambers and first published in 1728; six more editions appeared between 1728 and 1751 with a Supplement in 1753. The Cyclopædia was one of the first general encyclopedias to be produced in English.

Richard Pynson was one of the first printers of English books. Born in Normandy, he moved to London, where he became one of the leading printers of the generation following William Caxton. His books were printed to a high standard of craftsmanship, and his Morton Missal (1500) is regarded as among the finest books printed in England in the period.

A subscription library is a library that is financed by private funds either from membership fees or endowments. Unlike a public library, access is often restricted to members, but access rights can also be given to non-members, such as students.

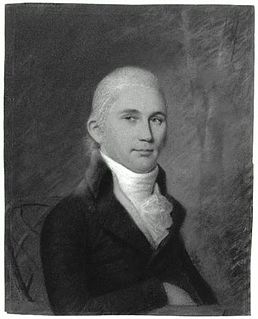

Joseph Dennie was an American author and journalist who was one of the foremost men of letters of the Federalist Era. A Federalist, Dennie is best remembered for his series of essays entitled The Lay Preacher and as the founding editor of The Port Folio, a journal espousing classical republican values. Port Folio was the most highly regarded and successful literary publication of its time, and the first important political and literary journal in the United States. Timothy Dwight IV once referred to Dennie as "the Addison of America" and "the father of American Belles-Lettres."

James Russell Raven LittD FBA FSA is a British historian and Chairman of the English-Speaking Union of the Commonwealth.

The Threnodia Augustalis is a 517-line occasional poem written by John Dryden to commemorate the death of Charles II in February 1685. The poem was "rushed into print" within a month. The title is a reference to the classical threnody, a poem of mourning, and to Charles as a "new Augustus". It is subtitled "A Funeral-Pindarique Poem Sacred to the Happy Memory of King Charles II," and is one of several poems on the subject published at the time.

Elizabeth Hands was an English poet.

Thomas James Wise was a bibliophile who collected the Ashley Library, now housed by the British Library, and later became known for the literary forgeries and stolen documents that were resold or authenticated by him.

A miscellany is a collection of various pieces of writing by different authors. Meaning a mixture, medley, or assortment, a miscellany can include pieces on many subjects and in a variety of different forms. In contrast to anthologies, whose aim is to give a selective and canonical view of literature, miscellanies were produced for the entertainment of a contemporary audience and so instead emphasise collectiveness and popularity. Laura Mandell and Rita Raley state:

This last distinction is quite often visible in the basic categorical differences between anthologies on the one hand, and all other types of collections on the other, for it is in the one that we read poems of excellence, the "best of English poetry," and it is in the other that we read poems of interest. Out of the differences between a principle of selection and a principle of collection, then, comes a difference in aesthetic value, which is precisely what is at issue in the debates over the "proper" material for inclusion into the canon.

Edward Kimber (1719–1769) was an English novelist, journalist and compiler of reference works.

Robert George Collier Proctor, often published as R. G. C. Proctor, was an English bibliographer, librarian, book collector, and expert on incunabula and early typography.

William Shaw (1749–1831) was a Scottish Gaelic scholar, writer, minister and Church of England cleric. He is known also as friend and biographer of Samuel Johnson. His 1781 paper on the Ossian controversy is still considered a good survey of critical points.

Arthur MacLoughlin Broome was an English clergyman and campaigner for animal welfare. He was one of a group of creators of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) in 1824. Broome was appointed as the original society's first Secretary, a post he held until 1828. He held posts at various churches in London, Essex, and Kent, and supported an appeal for earthquake relief in Syria. He wrote about animal theology and also about two 17th-century English clergy. He was guarantor for the RSPCA's debts, which led to his financial ruin and in April 1826 he was sent to a debtors' prison.

Isabella Lickbarrow was an English poet from Kendal who is sometimes associated with the Lake Poets. She published two collections: Poetical Effusions (1814) and A Lament upon the Death of Her Royal Highness the Princess Charlotte; and Alfred, a Vision (1818). Her work covers a wide variety of subjects, but scholars have noted in particular her topographical poetry and political poetry about the Napoleonic Wars.

Susan Smythies was a British story writer from Colchester in Essex.