This article concerns the period 279 BC – 270 BC.

Year 279 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Publius Sulpicius Saverrio and Publius Decius Mus. The denomination 279 BC for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for many years.

Pyrrhus was a Greek king and statesman of the Hellenistic period. He was king of the Molossians, of the royal Aeacid house, and later he became king of Epirus. He was one of the strongest opponents of early Rome, and had been regarded as one of the greatest generals of antiquity. Several of his victorious battles caused him unacceptably heavy losses, from which the term "Pyrrhic victory" was coined.

Publius Valerius Laevinus was commander of the Roman forces at the Battle of Heraclea in 280 BC, in which he was defeated by Pyrrhus of Epirus. In his Life of Pyrrhus, Plutarch wrote that Gaius Fabricius Luscinus said of this battle that it was not the Epirots who had beaten the Romans, but only Pyrrhus who had beaten Laevinus.

The Battle of Heraclea took place in 280 BC between the Romans under the command of consul Publius Valerius Laevinus, and the combined forces of Greeks from Epirus, Tarentum, Thurii, Metapontum, and Heraclea under the command of Pyrrhus, king of Epirus. Although the battle was a victory for the Greeks and their casualties were lower than the Romans, they had lost many veteran soldiers that would be hard to replace on foreign soil.

The Battle of Asculum took place near Asculum in 279 BC between the Roman Republic under the command of the consuls Publius Decius Mus and Publius Sulpicius Saverrio, and the forces of King Pyrrhus of Epirus. The battle took place during the Pyrrhic War, after the Battle of Heraclea of 280 BC, which was the first battle of the war. There exist accounts of this battle by three ancient historians: Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Plutarch, and Cassius Dio. Asculum was in Lucanian territory, in southern Italy. The Battle of Asculum was the original “Pyrrhic victory”.

The Pyrrhic War was largely fought between the Roman Republic and Pyrrhus, the king of Epirus, who had been asked by the people of the Greek city of Tarentum in southern Italy to help them in their war against the Romans.

The Battle of Beneventum was the last battle of the Pyrrhic War. It was fought near Beneventum, in southern Italy, between the forces of Pyrrhus, king of Epirus in Greece, and the Romans, led by consul Manius Curius Dentatus. The result was a Roman victory and Pyrrhus was forced to return to Tarentum, and later to Epirus.

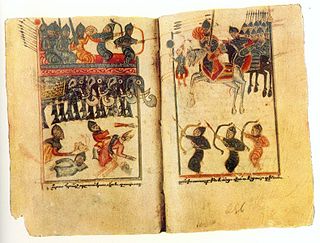

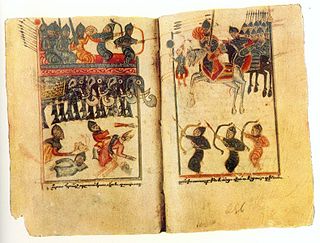

The Battle of Singara was fought in 344 between Roman and Sasanian Persian forces. The Romans were led in person by Emperor Constantius II, while the Persian army was led by King Shapur II of Persia. It is the only one of the nine pitched battles recorded to have been fought in a war of over twenty years, marked primarily by indecisive siege warfare, of which any details have been preserved. Although the Persian forces prevailed on the battlefield, both sides suffered heavy casualties.

The Battle of Avarayr was fought on 26 May 451 on the Avarayr Plain in Vaspurakan between a Christian Armenian army under Vardan Mamikonian and Sassanid Persia. It is considered one of the first battles in defense of the Christian faith. Although the Persians were victorious on the battlefield, it was a pyrrhic victory as Avarayr paved the way to the Nvarsak Treaty of 484, which affirmed Armenia's right to practise Christianity freely.

Publius Decius Mus was a Roman politician and general of the plebeian gens Decia. He was the son of Publius Decius Mus, who was consul in 312 BC. As consul in 279 BC, he and his fellow consul, Publius Sulpicius Saverrio, combined their armies against Pyrrhus of Epirus at the Battle of Asculum.

Ascoli Satriano is a town and comune in the province of Foggia in the Apulia region of southeast Italy. It is located on the edge of a large plain in Northern Apulia known as the Tavoliere delle Puglie.

The siege of Sparta took place in 272 BC and was a battle fought between Epirus, led by King Pyrrhus, and an alliance consisting of Sparta, under the command of King Areus I and his heir Acrotatus, and Macedon. The battle was fought at Sparta and ended in a Spartan-Macedonian victory.

Epirus was an ancient Greek kingdom, and later republic, located in the geographical region of Epirus, in parts of north-western Greece and southern Albania. Home to the ancient Epirotes, the state was bordered by the Aetolian League to the south, Ancient Thessaly and Ancient Macedonia to the east, and Illyrian tribes to the north. The Greek king Pyrrhus is known to have made Epirus a powerful state in the Greek realm that was comparable to the likes of Ancient Macedonia and Ancient Rome. Pyrrhus' armies also attempted an assault against the state of Ancient Rome during their unsuccessful campaign in what is now modern-day Italy.

Pyrrhus' invasion of the Peloponnese in 272 BC was an invasion of south Greece by Pyrrhus, King of Epirus. He was opposed by Macedon and a coalition of Greek city-states (poleis), most notably Sparta. The war ended in a joint victory by Macedonia and Sparta.

Due to the Roman focus on infantry and its discipline, war elephants were rarely used. While the Romans did eventually adopt them, and used them occasionally after the Punic wars, especially during the conquest of Greece, they fell out of use by the time of Claudius, after which they were generally used for the purpose of demoralizing enemies instead of being used for tactical purposes. The Romans occasionally used them for transport.

The Battle of Argos of 272 BC was fought between the forces of Pyrrhus, the king of Epirus, and a spontaneous alliance between the city state of Argos, the Spartan king Areus I and the Macedonian king Antigonus Gonatas. The battle ended with the death of Pyrrhus and the surrender of his army.

The Battle of Asculum was a battle of the Pyrrhic War between the Roman Republic and the forces of King Pyrrhus of Epirus.

The Battle of Eryx was one of the battles in the Pyrrhic War. It was held between the Kingdom of Epirus and the Magna Graecia of the Empire of Carthage, as part of the Sicilian Front in the Pyrrhic War. It ended in an Epirote victory.