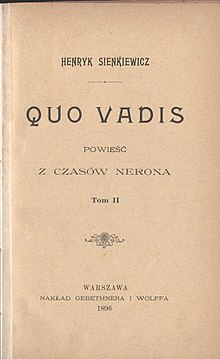

Henryk Adam Aleksander Pius Sienkiewicz, also known by the pseudonym Litwos, was an epic Polish writer. He is remembered for his historical novels, such as the Trilogy series and especially for his internationally known best-seller Quo Vadis (1896).

Quo vadis? is a Latin phrase meaning "Where are you going?" It is commonly translated, quoting the KJV translation of John 13:36, as "Whither goest thou?"

Santa Maria in Palmis, also known as Chiesa del Domine Quo Vadis, is a small church southeast of Rome. It is located about some 800 m from Porta San Sebastiano, where the Via Ardeatina branches off the Appian Way, on the site where, according to the apocryphal Acts of Peter, Saint Peter met the risen Christ while Peter was fleeing persecution in Rome. According to the tradition, Peter asked him, "Lord, where are you going?". Christ answered, "I am going to Rome to be crucified again".

Ofonius Tigellinus was a prefect of the Roman imperial bodyguard, known as the Praetorian Guard, from 62 until 68, during the reign of emperor Nero. Tigellinus gained imperial favour through his acquaintance with Nero's mother Agrippina the Younger, and was appointed prefect upon the death of his predecessor Sextus Afranius Burrus, a position Tigellinus held first with Faenius Rufus and then Nymphidius Sabinus.

Quo Vadis is a 1951 American religious epic film set in ancient Rome during the final years of Emperor Nero's reign, based on the 1896 novel of the same title by Polish Nobel Laureate author Henryk Sienkiewicz. Produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and filmed in Technicolor, it was directed by Mervyn LeRoy from a screenplay by S. N. Behrman, Sonya Levien, and John Lee Mahin. It is the fourth screen adaptation of Sienkiewicz's novel. The film stars Robert Taylor, Deborah Kerr, Leo Genn, and Peter Ustinov, and features Patricia Laffan, Finlay Currie, Abraham Sofaer, Marina Berti, Buddy Baer, and Felix Aylmer. Future Italian stars Sophia Loren and Bud Spencer appeared as uncredited extras. The score is by Miklós Rózsa and the cinematography by Robert Surtees and William V. Skall. The film was released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer on November 2, 1951.

Aulus Plautius was a Roman politician and general of the mid-1st century. He began the Roman conquest of Britain in 43, and became the first governor of the new province, serving from 43 to 46.

Gaius Petronius Arbiter was a Roman courtier during the reign of Nero. He is generally believed to be the author of the Satyricon, a satirical novel believed to have been written during the Neronian era. He is one of the most important characters in Henryk Sienkiewicz' historical novel Quo Vadis (1895). Leo Genn portrays him in the 1951 film of the same name.

The conspiracy of Gaius Calpurnius Piso in 65 CE was a major turning point in the reign of the Roman emperor Nero. The plot reflected the growing discontent among the ruling class of the Roman state with Nero's increasingly despotic leadership, and as a result is a significant event on the road toward his eventual suicide and the chaos of the Year of the Four Emperors which followed.

Pomponia is the female name for the Pomponia gens of Ancient Rome. This family was one of the oldest families in Rome. Various women bearing this name lived during the Middle and Late Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. The oldest known Pomponia was mother of a famous Roman general; the second and third were related to each other. The relationship between these women, if any, is not known. They descended from Pomponius, the first son of Numa Pompilius, the second King of Rome.

Pomponia Graecina was a noble Roman woman of the 1st century who was related to the Julio-Claudian dynasty. She was the wife of Aulus Plautius, the general who led the Roman conquest of Britain in 43 AD, and was renowned as one of the few people who dared to publicly mourn the death of a kinswoman killed by the Imperial family. It has been speculated that she was an early Christian. She is identified by some as Lucina or Lucy, a saint honoured by the Roman Catholic Church.

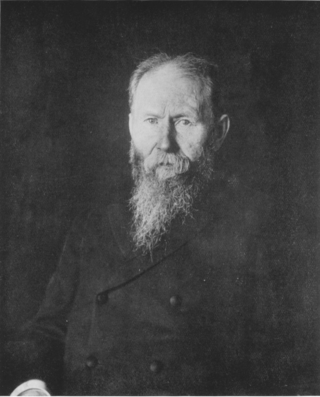

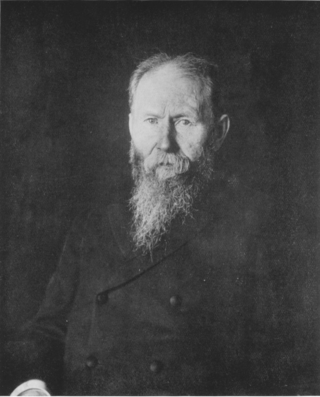

Jeremiah Curtin was an American ethnographer, folklorist, and translator. Curtin had an abiding interest in languages and was conversant with several. From 1883 to 1891 he was employed by the Bureau of American Ethnology as a field researcher documenting the customs and mythologies of various Native American tribes.

Marcus Vinicius was twice Roman consul and, as husband of Julia Livilla, grandson-in-law (progener) of the emperor Tiberius. He was the son and grandson of two consuls, Publius Vinicius and Marcus Vinicius.

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus and his reign have featured in music, literature, the arts, and in business.

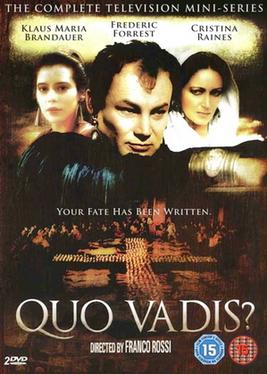

Quo Vadis? is a 1985 international television miniseries made by Radiotelevisione Italiana, Antenne 2, Polyphon Film- und Fernsehgesellschaft, Channel 4 Television, Televisión Española and Televisione Svizzera Italiana (TSI). It was directed by Franco Rossi and produced by Elio Scardamaglia and Francesco Scardamaglia. The script was by Ennio De Concini based on the 1896 novel Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz.

Quo Vadis is a 2001 Polish film directed by Jerzy Kawalerowicz based on the 1896 book of the same title by Henryk Sienkiewicz. It was Poland's submission to the 74th Academy Awards for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, but was not nominated.

The Sign of the Cross is an 1895 four-act historical tragedy, by Wilson Barrett and popular for several decades. Barrett said its Christian theme was his attempt to bridge the gap between Church and stage. The plot resembles that of Henryk Sienkiewicz's historical novel Quo Vadis, which was first published between 26 March 1895 and 29 February 1896 in the Gazeta Polska, 11 months after the play's first production.

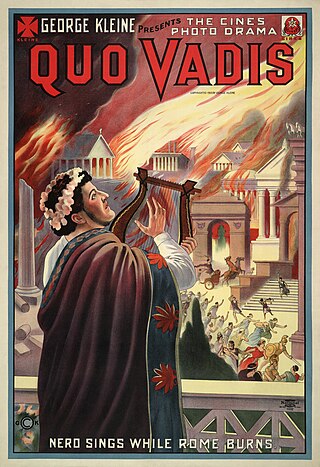

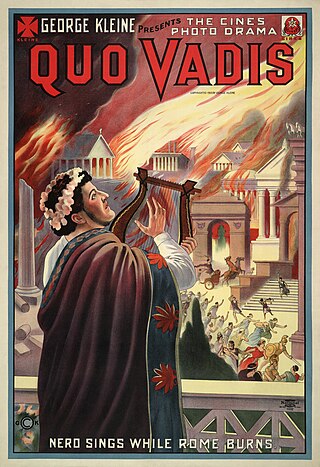

Quo Vadis is an Italian film directed by Enrico Guazzoni for Cines in 1913, based on the 1896 novel of the same name written by Henryk Sienkiewicz. It was one of the first blockbusters in the history of cinema, with 5,000 extras, lavish sets, and a lengthy running time of two hours, setting the standard for "superspectacles" for decades to come.

Quo Vadis is a 1924 Italian silent historical drama film directed by Gabriellino D'Annunzio and Georg Jacoby and starring Emil Jannings, Elena Sangro, and Lillian Hall-Davis. It is based on the 1896 novel Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz which was notably later adapted into a 1951 film.

The 1905 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the Polish novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846–1916) "because of his outstanding merits as an epic writer." He was given the prize on 10 December 1905. He is the first Polish author to win the Nobel Prize in the literary category and the second Polish citizen to win in general after the chemist Maria Skłodowska Curie in 1903. He was followed by Władysław Reymont in 1924.

Quo Vadis, sometimes given as Quo Vadis?, is a play in six acts by Stanislaus Stange that is based on Henryk Sienkiewicz's 19th century novel of the same name. It should not be confused with the play of the same name by Jeannette Leonard Gilder which also was staged on Broadway in the year 1900 during the same period of time.