Related Research Articles

Thomas Cranmer was a theologian, leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He is honoured as a martyr in the Church of England.

Edmund Grindal was Bishop of London, Archbishop of York, and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Elizabeth I. Though born far from the centres of political and religious power, he had risen rapidly in the church during the reign of Edward VI, culminating in his nomination as Bishop of London. However, the death of the King prevented his taking up the post, and along with other Marian exiles, he was a supporter of Calvinist Puritanism. Grindal sought refuge in continental Europe during the reign of Mary I. Upon Elizabeth's accession, Grindal returned and resumed his rise in the church, culminating in his appointment to the highest office.

Matthew Parker was an English bishop. He was the Archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England from 1559 to his death. He was also an influential theologian and arguably the co-founder of a distinctive tradition of Anglican theological thought.

William Warham was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1503 to his death in 1532.

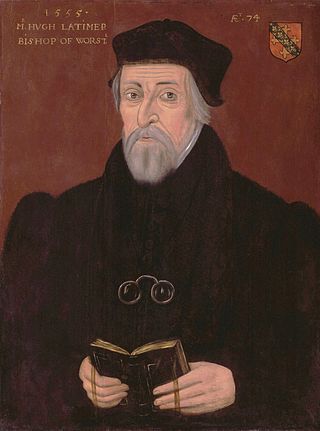

Hugh Latimer was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, and Bishop of Worcester during the Reformation, and later Church of England chaplain to King Edward VI. In 1555 under the Catholic Queen Mary I he was burned at the stake, becoming one of the three Oxford Martyrs of Anglicanism.

William Paget, 1st Baron Paget of Beaudesert, was an English statesman and accountant who held prominent positions in the service of Henry VIII, Edward VI and Mary I. He was the patriarch of the Paget family, whose descendants were created Earl of Uxbridge (1714) and Marquess of Anglesey (1815).

Sir John Cheke was an English classical scholar and statesman. One of the foremost teachers of his age, and the first Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Cambridge, he played a great part in the revival of Greek learning in England. He was tutor to Prince Edward, the future King Edward VI, and also sometimes to Princess Elizabeth. Of strongly Reformist sympathy in religious affairs, his public career as provost of King's College, Cambridge, Member of Parliament and briefly as Secretary of State during King Edward's reign was brought to a close by the accession of Queen Mary in 1553. He went into voluntary exile abroad, at first under royal licence. He was captured and imprisoned in 1556, and recanted his faith to avoid death by burning. He died not long afterward, reportedly regretting his decision.

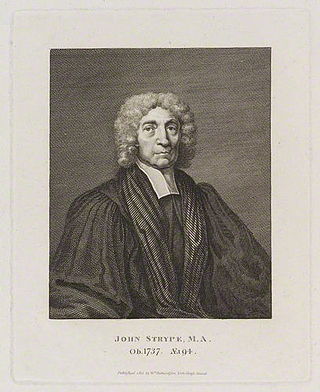

John Strype was an English clergyman, historian and biographer from London. He became a merchant when settling in Petticoat Lane. In his twenties, he became perpetual curate of Theydon Bois, Essex and later became curate of Leyton; this allowed him direct correspondence with several highly notable ecclesiastical figures of his time. He wrote extensively in his later years.

John Bell was a Bishop of Worcester (1539–1543), who served during the reign of Henry VIII of England.

James Brooks was an English Catholic clergyman and Bishop of Gloucester.

Nicholas Shaxton was Bishop of Salisbury. For a time, he had been a Reformer, but recanted this position, returning to the Roman faith. Under Henry VIII, he attempted to persuade other Protestant leaders to also recant. Under Mary I, he took part in several heresy trials of those who became Protestant martyrs.

Jane Neville, Countess of Westmorland, was an English noblewoman who had a role in the Northern Rebellion in 1569 against Elizabeth I of England.

Henry Cole was a senior English Roman Catholic churchman and academic.

John White was a Headmaster and Warden of Winchester College during the English Reformation who, remaining staunchly Roman Catholic in duty to his mentor Stephen Gardiner, became Bishop of Lincoln and finally Bishop of Winchester during the reign of Queen Mary. For several years he led the college successfully through very difficult circumstances. A capable if somewhat scholastic composer of Latin verse, he embraced the rule of Philip and Mary enthusiastically and vigorously opposed the Reformation theology.

Dr Richard Gwent was a senior ecclesiastical jurist, pluralist cleric and administrator through the period of the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII. Of south Welsh origins, as a Doctor of both laws in the University of Oxford he rose swiftly to become Dean of the Arches and Archdeacon of London and of Brecon, and later of Huntingdon. He became an important figure in the operations of Thomas Cromwell, was a witness to Thomas Cranmer's private protestation on becoming Archbishop of Canterbury, and was Cranmer's Commissary and legal draftsman. He was an advocate on behalf of Katherine of Aragon in the proceedings against her, and helped to deliver the decree of annulment against Anne of Cleves.

Edward Crome was an English reformer and courtier.

John Barber was an English clergyman and civilian.

John London, DCL was Warden of New College, Oxford, and a prominent figure in the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the reign of Henry VIII of England.

Anthony Hussey, Esquire, was an English merchant and lawyer who was President Judge of the High Court of Admiralty under Henry VIII, before becoming Principal Registrar to the Archbishops of Canterbury from early in the term of Archbishop Cranmer, through the restored Catholic primacy of Cardinal Pole, and into the first months of Archbishop Parker's incumbency, taking a formal part in the latter's consecration. The official registers of these leading figures of the English Reformation period were compiled by him. While sustaining this role, with that of Proctor of the Court of the Arches and other related ecclesiastical offices as a Notary public, he acted abroad as agent and factor for Nicholas Wotton.

Joan or Jane Wilkinson (d.1556) was silkwoman to Anne Boleyn and Lady Lisle and a Protestant reformer. She was a friend of other leading reformers, including Bishops John Hooper and Hugh Latimer. During the reign of Mary I, she became a religious exile, and died at Frankfurt in 1556.

References

- ↑ p.1, Thomas Cranmer: A Life by Diarmaid Macculloch, 1997, Yale University Press

- 1 2 3 4 5 Archbold 1894.

- ↑ Brooks, Christopher W. "Morice, James". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37783.(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Null, Ashley. "Morice, Ralph". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19253.(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Archbold, William Arthur Jobson (1894). "Morice, Ralph". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography . Vol. 39. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Archbold, William Arthur Jobson (1894). "Morice, Ralph". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography . Vol. 39. London: Smith, Elder & Co.