Pennsylvania Avenue is a primarily diagonal street in Washington, D.C., and Prince George's County, Maryland, that connects the United States Capitol with the White House and then crosses northwest Washington, D.C. to Georgetown. Traveling through southeast Washington from the Capitol, it enters Maryland, and becomes MD Route 4 and then MD Route 717 in Upper Marlboro, and finally Stephanie Roper Highway.

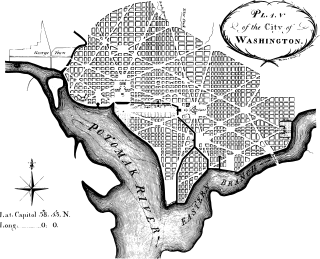

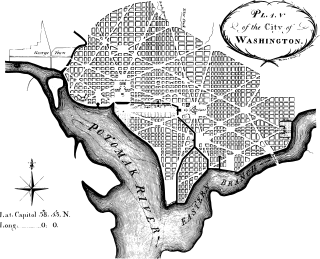

Pierre "Peter" Charles L'Enfant was an American-French military engineer who in 1791 designed the basic plan for Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. His work is known today as the L'Enfant Plan. He also inspired the street plan for Detroit, Michigan.

Dupont Circle is a historic roundabout park and neighborhood of Washington, D.C., located in Northwest D.C. The Dupont Circle neighborhood is bounded approximately by 16th Street NW to the east, 22nd Street NW to the west, M Street NW to the south, and Florida Avenue NW to the north. Much of the neighborhood is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. However, the local government Advisory Neighborhood Commission and the Dupont Circle Historic District have slightly different boundaries.

The Washington meridians are four meridians that were used as prime meridians in the United States which pass through Washington, D.C. The four that have been specified are:

- through the Capitol

- through the White House

- through the old Naval Observatory

- through the new Naval Observatory.

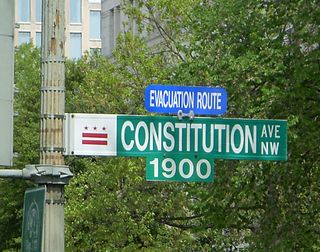

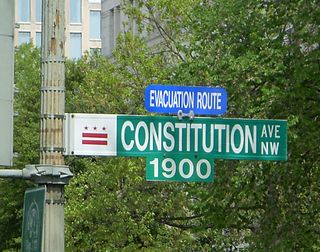

Constitution Avenue is a major east–west street in the northwest and northeast quadrants of the city of Washington, D.C., in the United States. It was originally known as B Street, and its western section was greatly lengthened and widened between 1925 and 1933. It received its current name on February 26, 1931, though it was almost named Jefferson Avenue in honor of Thomas Jefferson.

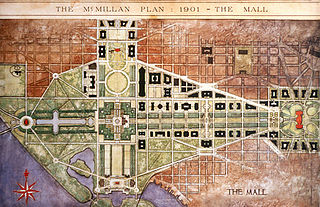

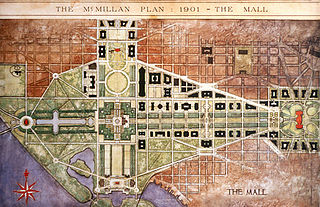

The history of Washington, D.C., is tied to its role as the capital of the United States. The site of the District of Columbia along the Potomac River was first selected by President George Washington. The city came under attack during the War of 1812 in an episode known as the Burning of Washington. Upon the government's return to the capital, it had to manage the reconstruction of numerous public buildings, including the White House and the United States Capitol. The McMillan Plan of 1901 helped restore and beautify the downtown core area, including establishing the National Mall, along with numerous monuments and museums.

Andrew Ellicott was an American land surveyor who helped map many of the territories west of the Appalachians, surveyed the boundaries of the District of Columbia, continued and completed Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's work on the plan for Washington, D.C., and served as a teacher in survey methods for Meriwether Lewis.

Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site is a National Historic Site in the city of Washington, D.C. Established on September 30, 1965, the site is roughly bounded by Constitution Avenue, 15th Street NW, F Street NW, and 3rd Street NW. The historic district includes a number of culturally, aesthetically, and historically significant structures and places, including Pennsylvania Avenue NW from the White House to the United States Capitol, the Treasury Building, Freedom Plaza, Federal Triangle, Ford's Theatre, the Old Patent Office Building, the Old Pension Office Building, which now houses the National Building Museum, Judiciary Square, and the Peace Monument.

Rhode Island Avenue is a diagonal avenue in the Northwest and Northeast quadrants of Washington, D.C., and the capital's inner suburbs in Prince George's County, Maryland. Paralleling New York Avenue, Rhode Island Avenue was one of the original streets in Pierre L'Enfant's plan for the capital. It became a major commuter route, carrying U.S. Route 1 traffic into the city from Prince George's County.

Florida Avenue is a major street in Washington, D.C. It was originally named Boundary Street, because it formed the northern boundary of the Federal City under the 1791 L'Enfant Plan. With the growth of the city beyond its original borders, Boundary Street was renamed Florida Avenue in 1890.

Jefferson Pier, Jefferson Stone, or the Jefferson Pier Stone, in Washington, D.C., marks the second prime meridian of the United States even though it was never officially recognized, either by presidential proclamation or by a resolution or act of Congress.

Tiber Creek or Tyber Creek, originally named Goose Creek, is a tributary of the Potomac River in Washington, D.C. It was a free-flowing creek until 1815, when it was channeled to become part of the Washington City Canal. Presently, it flows under the city in tunnels, including under Constitution Avenue NW.

The streets and highways of Washington, D.C., form the core of the surface transportation infrastructure in Washington, D.C., the federal capital of the United States. Given that it is a planned city, the city's streets follow a distinctive layout and addressing scheme. There are 1,500 miles (2,400 km) of public roads in the city, of which 1,392 miles (2,240 km) are owned and maintained by city government.

The McMillan Plan is a comprehensive planning document for the development of the monumental core and the park system of Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States. It was written in 1902 by the Senate Park Commission. The commission is popularly known as the McMillan Commission after its chairman, Senator James McMillan of Michigan.

Downtown is the central business district of Washington, D.C., located in Northwest D.C. It is the fourth largest central business district in the United States. The "Traditional Downtown" has been defined as an area roughly between Union Station in the east and 16th Street NW in the west, and between the National Mall on the south and Massachusetts Avenue on the north, including Penn Quarter. However, nowadays, Downtown D.C. usually refers to a larger area, as the DC Office of Planning states:

…most residents, workers, and visitors think of Downtown in a broader sense — including areas as far north as Dupont Circle, as far west as Foggy Bottom, and as far east as Capitol Hill. Only about half of the central city workforce is located within the city’s traditional Downtown.

Vlastimil Koubek was a Czech American architect who designed more than 100 buildings, most of them in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area. When he died, he had designed buildings worth more than $2 billion. Most of his work is Modernist in style, although he developed a few structures in other vernaculars. He created the site plan for the redevelopment of Rosslyn, Virginia, and his Ames Center anchored the area's economic recovery. He also designed the World Building in Silver Spring, Maryland, which sparked redevelopment of that town's downtown and the L'Enfant Plaza Hotel in Washington, D.C., amongst many other buildings. In 1985, Washingtonian magazine considered him to be one of 20 people "who in the past 20 years had the greatest impact on the way we live and who forever altered the look of Washington." In 1988, The Washington Post newspaper said his Willard Hotel renovation was one of 28 projects in the area which made a signal contribution to the "feel" and look of Washington, D.C.

Paul Johannes Pelz was a German-American architect, best known as the main architect of the Library of Congress in Washington DC.

The L'Enfant Plan for the city of Washington is the urban plan developed in 1791 by Major Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant for George Washington, the first president of the United States.

The James V. Forrestal Building is a low-rise Brutalist office building in Washington, D.C. Originally known as Federal Office Building 5, and nicknamed the Little Pentagon, the Forrestal Building was constructed between 1965 and 1969 to accommodate United States armed forces personnel. It is named after James Forrestal, the first United States Secretary of Defense. It became the headquarters of the United States Department of Energy after that agency's creation in 1977.

According to accounts that began to appear during the 1960s or earlier, a substantial mythology has exaggerated the accomplishments of Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806), an African-American naturalist, mathematician, astronomer and almanac author who also worked as a surveyor and farmer.