Exile, judgment and salvation

Rastafari is sometimes described as a millenarian movement, [13] because early in its development it espoused the idea that the present age would come to an apocalyptic end and Black people would be released from their oppression in the modern world. [14] Rastafari teaches that the African diaspora are living as exiles in the Biblical "Babylon", and that they will be returned to "Zion" (or Africa) during the End Times. Babylon in this context refers to Western society, particularly in its corporate and materialistic state. [15] Babylon is a symbol of European colonialism, white supremacy and global capitalism. [16] Enforcers of the state, such as police and soldiers, are seen as Babylon's agents. [17]

As the Old Testament recounts how the ancient Israelites were exiled to Mesopotamia during the Babylonian captivity, [18] Rastas understand their own exile from Africa as a similar condition; thus the displacement of Africans during the slave trade is seen as an exile caused by the corruption of Babylon. [19] Rastas describe this exile of the African diaspora in terms of great suffering. [20]

In the New Testament, Babylon is used as a euphemism for the Roman Empire, which was prophesied to be destroyed in the Book of Revelation, making way for the Kingdom of God. Rastas see this as a description of the fall of Western colonialism, imperialism and white supremacy, which will be followed by the restoration of Zion—or Africa and its people. [18]

Many practitioners believe that on the Day of Judgment, Babylon will be overthrown, [21] with Rastas being among the chosen who survive. [22] With Babylon destroyed, Rastas believe that humanity will enter a "new age", [23] a millennium of peace, justice, and happiness in which the righteous shall live in Africa. [24] In the 1980s, many Rastas believed that the Day of Judgment would happen around the year 2000. [25] A view then common in the Rasta community was that the world's white people would wipe themselves out through nuclear war, [26] with Africans able to rule the world, something they believed was prophesied in the Book of Daniel. [a] [26]

The Promised Land

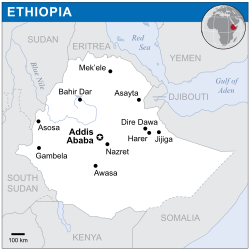

Rastas view the Promised Land, or Zion, as an ideal to which they aspire, as well as a physical place they can return to in Africa. It is not an afterlife, but a reward which will be granted to the faithful in this world. At the time of the Second Coming of Jesus (whom many Rastas believe was Haile Selassie I), the restoration of the Rastafari to Zion will begin. As with "Babylon", the name "Zion" comes from the Bible, [27] although Rastas use it to refer to Africa as a whole, along with another Biblical name for the continent, "Ethiopia". [28] Ghanaian Rastas, for instance, describe themselves as already living within Ethiopia. [29] Other Rastas use the term "Zion" to mean the country of Ethiopia specifically, a free and decolonised Jamaica, or even a state of mind. [19] Rastas believe that the literal or spiritual return to Africa will allow them to escape the domination and degradation they experience every day in Babylon. [30]

While early Rastafari drew on the Back-to-Africa movement, emphasising the need for the African diaspora to be repatriated to Africa, this focus began to decline after the 1960s. [31] Critics of the repatriation movement argued that the migration of the entire African diaspora to Africa, given the size of the diaspora and the politics involved, was implausible. [32]

With the desire for physical repatriation to Africa relegated to a minor concern by the 1970s, [33] a change partially influenced by observation of the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia, [34] many Rastas came to see the idea of returning to Africa in a metaphorical sense. Africa can be a state of mind, or a state of harmony with nature in which Rastas can live wherever they are. This entails the restoration of their pride and self-confidence as people of African descent. [35] The term "liberation before repatriation" began to be used within the movement, signifying this shift in emphasis. [36]

Today, many Rastas seek to transform Western society so that they may more comfortably live within it rather than seeking to move to Africa. [37] There are nevertheless some Rastas who continue to emphasise the need for physical resettlement of the African diaspora in Africa. [33]