Related Research Articles

Domesday Book is a manuscript record of the Great Survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 at the behest of King William the Conqueror. The manuscript was originally known by the Latin name Liber de Wintonia, meaning "Book of Winchester", where it was originally kept in the royal treasury. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that in 1085 the king sent his agents to survey every shire in England, to list his holdings and dues owed to him.

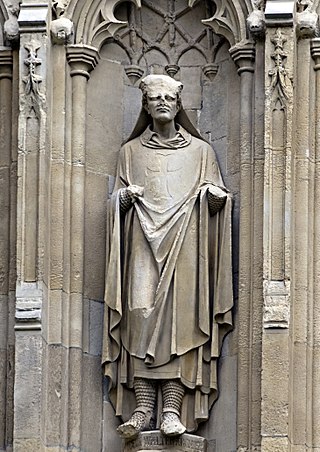

Hubert Walter was an influential royal adviser in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries in the positions of Chief Justiciar of England, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Chancellor. As chancellor, Walter began the keeping of the Charter Roll, a record of all charters issued by the chancery. Walter was not noted for his holiness in life or learning, but historians have judged him one of the most outstanding government ministers in English history.

In the civil service of the United Kingdom, His Majesty's Exchequer, or just the Exchequer, is the accounting process of central government and the government's current account in the Consolidated Fund. The term is used in various financial documents, including the latest departmental and agency annual accounts.

Scutage was a medieval English tax levied on holders of a knight's fee under the feudal land tenure of knight-service. Under feudalism the king, through his vassals, provided land to knights for their support. The knights owed the king military service in return. The knights were allowed to "buy out" of the military service by paying scutage.

Sir Francis Palgrave, was an English archivist and historian. He was Deputy Keeper of the Public Record Office from its foundation in 1838 until his death; and he is also remembered for his many scholarly publications.

The Dialogus de Scaccario, or Dialogue concerning the Exchequer, is a mediaeval treatise on the practice of the English Exchequer written in the late 12th century by Richard FitzNeal. The treatise, written in Latin, and known from four manuscripts from the 13th century is set up as a series of questions and answers, covering the jurisdiction, constitution and practice of the Exchequer. One academic said that "The value of this essay for early English history cannot be over-estimated; in every direction it throws light upon the existing state of affairs." It has been repeatedly republished and translated, most recently in 2007.

The Trial of the Pyx is a judicial ceremony in the United Kingdom to ensure that newly minted coins from the Royal Mint conform to their required dimensional and fineness specifications. Although coin quality is now tested throughout the year under laboratory conditions, the event has become an annual historic tradition. Each year, thousands of coins are put on trial, consisting of both those struck for circulation and non-circulating commemorative coins.

Kingston Russell House is a large mansion house and manor near Long Bredy in Dorset, England, west of Dorchester. The present house dates from the late 17th century but in 1730 was clad in a white Georgian stone facade. The house was restored in 1913, and at the same time the gardens were laid out.

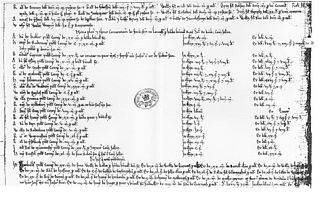

The Pipe rolls, sometimes called the Great rolls or the Great Rolls of the Pipe, are a collection of financial records maintained by the English Exchequer, or Treasury, and its successors, as well as the Exchequer of Ireland. The earliest date from the 12th century, and the series extends, mostly complete, from then until 1833. They form the oldest continuous series of records concerning English governance kept by the English, British, Irish and United Kingdom governments, covering a span of about 700 years. The early medieval ones are especially useful for historical study, as they are some of the earliest financial records available from the Middle Ages. A similar set of records was developed for Normandy, which was ruled by the English kings from 1066 to 1205, but the Norman Pipe rolls have not survived in a continuous series like the English.

Under feudalism in France and England during the Middle Ages, tenure by serjeanty was a form of tenure in return for a specified duty other than standard knight-service.

Knight-service was a form of feudal land tenure under which a knight held a fief or estate of land termed a knight's fee from an overlord conditional on him as a tenant performing military service for his overlord.

Berwick Castle is a ruined castle in Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland, England.

(John) Horace Round was a historian and genealogist of the English medieval period. He translated the portion of Domesday Book (1086) covering Essex into English. As an expert in the history of the British peerage, he was appointed honorary historical adviser to the Crown.

The Chronicles and Memorials of Great Britain and Ireland during the Middle Ages, widely known as the Rolls Series, is a major collection of British and Irish historical materials and primary sources published as 99 works in 253 volumes between 1858 and 1911. Almost all the great medieval English chronicles were included: most existing editions, published by scholars of the 17th and 18th centuries, were considered to be unsatisfactory. The scope was also extended to include legendary, folklore and hagiographical materials, and archival records and legal tracts.

The patent rolls are a series of administrative records compiled in the English, British and United Kingdom Chancery, running from 1201 to the present day.

The Close Rolls are an administrative record created in medieval England, Wales, Ireland and the Channel Islands by the royal chancery, in order to preserve a central record of all letters close issued by the chancery in the name of the Crown.

Thomas Madox was a legal antiquary and historian, known for his publication and discussion of medieval records and charters; and in particular for his History of the Exchequer, tracing the administration and records of that branch of the state from the Norman Conquest to the time of Edward II. It became a standard work for the study of English medieval history. He held the office of historiographer royal from 1708 until his death.

The Book of Fees is the colloquial title of a modern edition, transcript, rearrangement and enhancement of the medieval Liber Feodorum which is a listing of feudal landholdings or fief, compiled in about 1302, but from earlier records, for the use of the English Exchequer. Originally in two volumes of parchment, the Liber Feodorum is a collection of about 500 written brief notes made between 1198 and 1292 concerning fiefs held in capite or in-chief, that is to say directly from the Crown.

The Record Commissions were a series of six Royal Commissions of Great Britain and the United Kingdom which sat between 1800 and 1837 to inquire into the custody and public accessibility of the state archives. The Commissioners' work paved the way for the establishment of the Public Record Office in 1838. The Commissioners were also responsible for publishing various historical records, including the Statutes of the Realm to 1714 and the Acts of Parliament of Scotland to 1707, as well as a number of important medieval records.

The Clerk of the Pipe was a post in the Pipe Office of the English Exchequer and its successors. The incumbent was responsible for the pipe rolls on which the government income and expenditure was recorded as credits and debits.

References

- 1 2 3 "Red Book of the Exchequer [catalogue entry]". The National Archives. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ The Red Book has been rebound in modern times: its historic binding, probably late 14th-century with a 17th-century inscription, is preserved separately in The National Archives under reference code E 166/2/1: see Hall 1896, pt I, p. xlix; "Red Book of the Exchequer (otherwise in E 164/2). Sheepskin chemise binding [catalogue entry]". The National Archives. Retrieved 28 April 2019..

- ↑ Round 1898, p. 17

- ↑ Hall 1896, pt I, pp. xxv–xlix.

- ↑ Hall 1896, pt I, p. iv.

- ↑ Downer 1972, pp. 46-47

- ↑ For a detailed table of contents, see Hall 1896, pt I, pp. lxv–cxlviii.

- ↑ Hall 1896, pt I, p. xlix.

- ↑ Hunter 1838, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Hall 1896, pt I, pp. xii–xix.

- 1 2 3 Hall 1896, pt I, p. x.

- ↑ Hunter 1838.

- ↑ The three volumes were published in March 1897, but bear the date 1896 on their title pages: see Procter 2014, pp. 522–3.

- ↑ British National Archives. Sectional List. Vol. 24. HMSO Books. 1981. p. 47.

- ↑ A brief summary of Hall's editorial policy appears in Hall 1896, pt I, p. lxiv.

- ↑ Procter 2014, pp. 514–15.

- ↑ Procter 2014, pp. 517–20.

- ↑ Procter 2014, pp. 520–30.

- ↑ Procter 2014, p. 527.

- ↑ Procter 2014, p. 529.

- ↑ Round 1898, pp. v–vi.

- ↑ Round 1898, p. vi.

- ↑ Procter 2014, p. 530.