In physics, the Coriolis force is an inertial force that acts on objects in motion within a frame of reference that rotates with respect to an inertial frame. In a reference frame with clockwise rotation, the force acts to the left of the motion of the object. In one with anticlockwise rotation, the force acts to the right. Deflection of an object due to the Coriolis force is called the Coriolis effect. Though recognized previously by others, the mathematical expression for the Coriolis force appeared in an 1835 paper by French scientist Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis, in connection with the theory of water wheels. Early in the 20th century, the term Coriolis force began to be used in connection with meteorology.

When a fluid flows around an object, the fluid exerts a force on the object. Lift is the component of this force that is perpendicular to the oncoming flow direction. It contrasts with the drag force, which is the component of the force parallel to the flow direction. Lift conventionally acts in an upward direction in order to counter the force of gravity, but it is defined to act perpendicular to the flow and therefore can act in any direction.

Free flying is a skydiving discipline that began in the late 1980s, involving falling free in various vertical orientations, as opposed to the traditional "belly-to-earth" orientation. The discipline is known to have originated when Olav Zipser began experimenting with non-traditional forms of Body flight. Zipser founded the Free Fly Clowns as a two-person competitive team with Mike Vail in 1992. He was joined by Omar Alhegelan, Charles Bryan, and Stefania Martinengo in 1994. The Free Fly Clowns are also credited with opening the first school to teach free flying, The First School of Modern Skydiving.

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere or through the vacuum of outer space. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift associated with gliding or propulsive thrust, aerostatically using buoyancy, or by ballistic movement.

Wind shear /ʃɪr/, sometimes referred to as wind gradient, is a difference in wind speed and/or direction over a relatively short distance in the atmosphere. Atmospheric wind shear is normally described as either vertical or horizontal wind shear. Vertical wind shear is a change in wind speed or direction with a change in altitude. Horizontal wind shear is a change in wind speed with a change in lateral position for a given altitude.

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack is the angle between a reference line on a body and the vector representing the relative motion between the body and the fluid through which it is moving. Angle of attack is the angle between the body's reference line and the oncoming flow. This article focuses on the most common application, the angle of attack of a wing or airfoil moving through air.

Jet force is the exhaust from some machine, especially aircraft, propelling the object itself in the opposite direction as per Newton's third law. An understanding of jet force is intrinsic to the launching of drones, satellites, rockets, airplanes and other airborne machines.

Wingsuit flying is the sport of skydiving using a webbing-sleeved jumpsuit called a wingsuit to add webbed area to the diver's body and generate increased lift, which allows extended air time by gliding flight rather than just free falling. The modern wingsuit, first developed in the late 1990s, uses a pair of fabric membranes stretched flat between the arms and flanks/thighs to imitate an airfoil, and often also between the legs to function as a tail and allow some aerial steering.

Aircraft flight mechanics are relevant to fixed wing and rotary wing (helicopters) aircraft. An aeroplane, is defined in ICAO Document 9110 as, "a power-driven heavier than air aircraft, deriving its lift chiefly from aerodynamic reactions on surface which remain fixed under given conditions of flight".

Retreating blade stall is a hazardous flight condition in helicopters and other rotary wing aircraft, where the retreating rotor blade has a lower relative blade speed, combined with an increased angle of attack, causing a stall and loss of lift. Retreating blade stall is the primary limiting factor of a helicopter's never exceed speed, VNE.

Tracking is a technique used by skydivers during freefall to increase their horizontal speed. Tracking is considered a fundamental skill in the sport because it allows multiple skydivers to gain separation from each other prior to deploying their parachutes. Nearly all licensing organizations mandate a student show proficiency at tracking in order to obtain their skydiving license.

An aircraft stabilizer is an aerodynamic surface, typically including one or more movable control surfaces, that provides longitudinal (pitch) and/or directional (yaw) stability and control. A stabilizer can feature a fixed or adjustable structure on which any movable control surfaces are hinged, or it can itself be a fully movable surface such as a stabilator. Depending on the context, "stabilizer" may sometimes describe only the front part of the overall surface.

Adverse yaw is the natural and undesirable tendency for an aircraft to yaw in the opposite direction of a roll. It is caused by the difference in lift and drag of each wing. The effect can be greatly minimized with ailerons deliberately designed to create drag when deflected upward and/or mechanisms which automatically apply some amount of coordinated rudder. As the major causes of adverse yaw vary with lift, any fixed-ratio mechanism will fail to fully solve the problem across all flight conditions and thus any manually operated aircraft will require some amount of rudder input from the pilot in order to maintain coordinated flight.

A bombsight is a device used by military aircraft to drop bombs accurately. Bombsights, a feature of combat aircraft since World War I, were first found on purpose-designed bomber aircraft and then moved to fighter-bombers and modern tactical aircraft as those aircraft took up the brunt of the bombing role.

Dissymmetry of lift in rotorcraft aerodynamics refers to an unequal amount of lift on opposite sides of the rotor disc. It is a phenomenon that affects single-rotor helicopters and autogyros in forward flight.

Parachuting and skydiving is a method of transiting from a high point in an atmosphere to the ground or ocean surface with the aid of gravity, involving the control of speed during the descent using a parachute or parachutes.

3D Aerobatics or 3D flying is a form of flying using flying aircraft to perform specific aerial maneuvers. They are usually performed when the aircraft had been intentionally placed in a stalled position for purposes of entertainment or display. They are also often referred to as post-stall maneuvers, as they occur after aerodynamic stall has occurred and standard control surface deflections, as used in flight, are not effective.

The Course Setting Bomb Sight (CSBS) is the canonical vector bombsight, the first practical system for properly accounting for the effects of wind when dropping bombs. It is also widely referred to as the Wimperis sight after its inventor, Harry Wimperis.

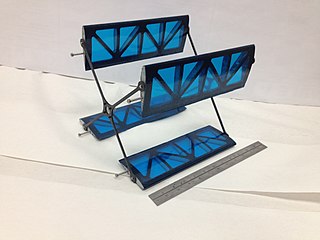

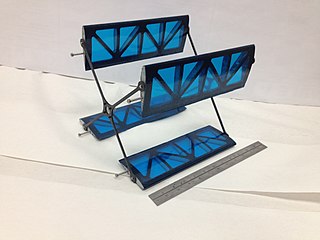

A cyclorotor, cycloidal rotor, cycloidal propeller or cyclogiro, is a fluid propulsion device that converts shaft power into the acceleration of a fluid using a rotating axis perpendicular to the direction of fluid motion. It uses several blades with a spanwise axis parallel to the axis of rotation and perpendicular to the direction of fluid motion. These blades are cyclically pitched twice per revolution to produce force in any direction normal to the axis of rotation. Cyclorotors are used for propulsion, lift, and control on air and water vehicles. An aircraft using cyclorotors as the primary source of lift, propulsion, and control is known as a cyclogyro or cyclocopter. A unique aspect is that it can change the magnitude and direction of thrust without the need of tilting any aircraft structures. The patented application, used on ships with particular actuation mechanisms both mechanical or hydraulic, is named after German company Voith Turbo.

This glossary of aerospace engineering terms pertains specifically to aerospace engineering, its sub-disciplines, and related fields including aviation and aeronautics. For a broad overview of engineering, see glossary of engineering.