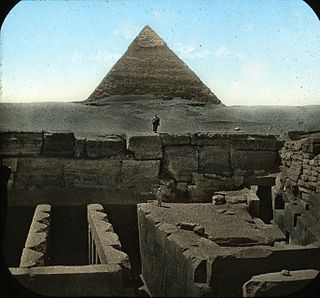

Menkaure or Menkaura was a king of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom. He is well known under his Hellenized names Mykerinos, in turn Latinized as Mycerinus, and Menkheres. According to Manetho, he was the throne successor of king Bikheris, but according to archaeological evidence, he was almost certainly the successor of Khafre. Africanus reports as rulers of the fourth dynasty Sôris, Suphis I, Suphis II, Mencherês (=Menkaure), Ratoisês, Bicheris, Sebercherês, and Thamphthis in this order. Menkaure became famous for his tomb, the Pyramid of Menkaure, at Giza and his statue triads, which showed him alongside the goddess Hathor and various regional deities.

Shepseskaf was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt, the sixth and probably last ruler of the fourth dynasty during the Old Kingdom period. He reigned most probably for four but possibly up to seven years in the late 26th to mid-25th century BC.

Neferirkare Kakai was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the third king of the Fifth Dynasty. Neferirkare, the eldest son of Sahure with his consort Meretnebty, was known as Ranefer A before he came to the throne. He acceded the day after his father's death and reigned for around 17 years, sometime in the early to mid-25th century BCE. He was himself very likely succeeded by his eldest son, born of his queen Khentkaus II, the prince Ranefer B who would take the throne as king Neferefre. Neferirkare fathered another pharaoh, Nyuserre Ini, who took the throne after Neferefre's short reign and the brief rule of the poorly known Shepseskare.

Djedkare Isesi was a pharaoh, the eighth and penultimate ruler of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt in the late 25th century to mid-24th century BC, during the Old Kingdom. Djedkare succeeded Menkauhor Kaiu and was in turn succeeded by Unas. His relationship to both of these pharaohs remain uncertain, although it is often conjectured that Unas was Djedkare's son, owing to the smooth transition between the two.

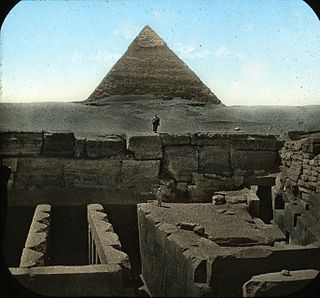

The pyramid of Menkaure is the smallest of the three main pyramids of the Giza pyramid complex, located on the Giza Plateau in the southwestern outskirts of Cairo, Egypt. It is thought to have been built to serve as the tomb of the Fourth Dynasty King Menkaure.

The Giza pyramid complex in Egypt is home to the Great Pyramid, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of Menkaure, along with their associated pyramid complexes and the Great Sphinx. All were built during the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom of ancient Egypt, between c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC. The site also includes several temples, cemeteries, and the remains of a workers' village.

Hemiunu was an ancient Egyptian prince who is believed to have been the architect of the Great Pyramid of Giza. As vizier, succeeding his father, Nefermaat, and his uncle, Kanefer, Hemiunu was one of the most important members of the court and responsible for all the royal works. His tomb lies close to west side Khufu's pyramid.

Zawyet El Aryan is a town in the Giza Governorate, located between Giza and Abusir. To the west of the town, just in the desert area, is a necropolis, referred to by the same name. Almost directly east across the Nile is Memphis. In Zawyet El Aryan, there are two pyramid complexes and five mastaba cemeteries.

Hetepheres I was a queen of Egypt during the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt who was a wife of one king, the mother of the next king, the grandmother of two more kings, and the figure who tied together two dynasties.

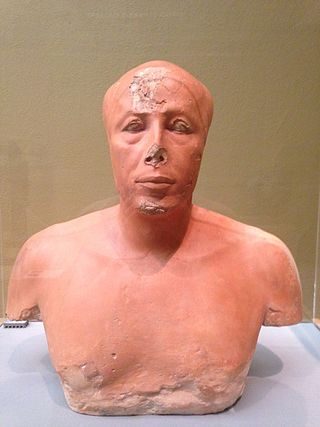

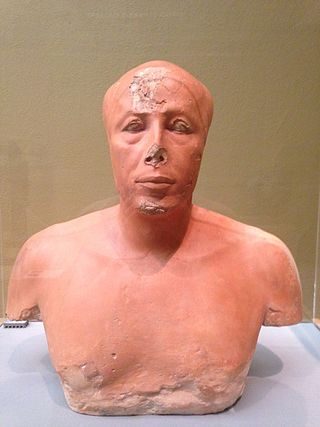

The painted limestone bust of Ankhhaf is an ancient Egyptian sculpture dating from the Old Kingdom. It is considered the work "of a master" of ancient Egyptian art, and can be seen at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Its catalog number is Museum Expedition 27.442.

Selim Hassan was an Egyptian Egyptologist.

Nebemakhet was a king's son and a vizier during the 4th Dynasty. Nebemakhet was the son of King Khafre and Queen Meresankh III. He is shown in his mother's tomb and in his own tomb at Giza.

Minkhaf I was an ancient Egyptian prince of the 4th Dynasty. He was a son of Pharaoh Khufu, half-brother of Pharaoh Djedefre and elder brother of Pharaoh Khafre. His mother may have been Queen Henutsen. Minkhaf had a wife and at least one son, but their names are not known. Minkhaf served as vizier possibly under Khufu or Khafre.

Nefermaat II was a member of the Egyptian royal family during the 4th Dynasty and vizier of Khafre.

Persenet was an ancient Egyptian queen consort of the 4th Dynasty. She may have been a daughter of Pharaoh Khufu and a wife of Pharaoh Khafre. She is mainly known from her tomb at Giza.

Raherka and Meresankh is a group statue of an ancient Egyptian couple of the 4th Dynasty or 5th Dynasty.

The Sphinx water erosion hypothesis is a fringe claim, contending that the Great Sphinx of Giza and its enclosing walls show erosion consistent with precipitation. Its proponents believe this dates the construction of the Sphinx to Predynastic Egypt or earlier. The hypothesis is inspired by the myth of Atlantis and it contradicts the mainstream view that the Sphinx was constructed contemporaneously with the Giza pyramid complex. Major proponents of the hypothesis include alternative Egyptologist John Anthony West, and geologist Robert Schoch.

The Egyptian dog Abuwtiyuw, also transcribed as Abutiu, was one of the earliest documented domestic animals whose name is known. He is believed to have been a royal guard dog who lived in the Sixth Dynasty (2345–2181 BC), and received an elaborate ceremonial burial in the Giza Necropolis at the behest of a pharaoh whose name is unknown.

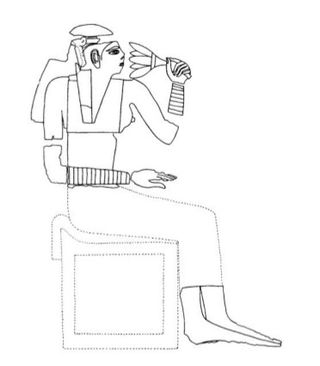

The Khufu Statuette or the Ivory figurine of Khufu is an ancient Egyptian statue. Historically and archaeologically significant, it was found in 1903 by Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie during excavation of Kom el-Sultan in Abydos, Egypt. It depicts Khufu, a Pharaoh of the Fourth dynasty, and the builder of the Great Pyramid, though it may have been carved much later, in the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty, 664 BC–525 BC.

The mask of Tutankhamun is a gold funerary mask that belonged to Tutankhamun, who reigned over the New Kingdom of Egypt from 1332 BC to 1323 BC, during the Eighteenth Dynasty. After being buried with Tutankhamun's mummy for over 3,000 years, it was found amidst the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb by the British archaeologist Howard Carter at the Valley of the Kings in 1925. Since then, it has been on display at the Egyptian Museum in the city of Cairo. In addition to being one of the best-known works of art in the world, it is a prominent symbol of ancient Egypt.