Related Research Articles

Divination is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout history, diviners ascertain their interpretations of how a querent should proceed by reading signs, events, or omens, or through alleged contact or interaction with a supernatural agency.

Fortune telling is the practice of predicting information about a person's life. The scope of fortune telling is in principle identical with the practice of divination. The difference is that divination is the term used for predictions considered part of a religious ritual, invoking deities or spirits, while the term fortune telling implies a less serious or formal setting, even one of popular culture, where belief in occult workings behind the prediction is less prominent than the concept of suggestion, spiritual or practical advisory or affirmation.

A binary code represents text, computer processor instructions, or any other data using a two-symbol system. The two-symbol system used is often "0" and "1" from the binary number system. The binary code assigns a pattern of binary digits, also known as bits, to each character, instruction, etc. For example, a binary string of eight bits can represent any of 256 possible values and can, therefore, represent a wide variety of different items.

Cleromancy is a form of sortition in which an outcome is determined by means that normally would be considered random, such as the rolling of dice (astragalomancy), but that are sometimes believed to reveal the will of a deity.

Scrying, also referred to as "seeing" or "peeping," is a practice rooted in divination and fortune-telling. It involves gazing into a medium, hoping to receive significant messages or visions that could offer personal guidance, prophecy, revelation, or inspiration. The practice lacks a definitive distinction from other forms of clairvoyance or divination but generally relies on visions within the chosen medium. Unlike augury, which interprets observable events, or divination, which follows standardized rituals, scrying's impressions arise within the medium itself.

Bibliomancy is the use of books in divination. The method of employing sacred books for 'magical medicine', for removing negative entities, or for divination is widespread in many religions of the world.

Alectryomancy is a form of divination in which the diviner observes a bird, several birds, or most preferably a white rooster or cockerel pecking at grain that the diviner has scattered on the ground. It was the responsibility of the pullularius to feed and keep the birds used. The observer may place grain in the shape of letters and thus discern a divinatory revelation by noting which letters the birds peck at, or the diviner may just interpret the pattern left by the birds' pecking in randomly scattered grain.

I Ching divination is a form of cleromancy applied to the I Ching. The text of the I Ching consists of sixty-four hexagrams: six-line figures of yin (broken) or yang (solid) lines, and commentaries on them. There are two main methods of building up the lines of the hexagram, using either 50 yarrow stalks or three coins. Some of the lines may be designated "old" lines, in which case the lines are subsequently changed to create a second hexagram. The text relating to the hexagram(s) and old lines is studied, and the meanings derived from such study can be interpreted as an oracle.

Sortes Sanctorum is a late antique text that was used for divination by means of dice. The oldest version of the text may have been pagan, but the earliest surviving example—a 4th- or 5th-century Greek fragment on papyrus—is Christian. The original version had 216 answers available depending on three ordered throws of a single die. It was later revised down to 56 answers for a single throw of three dice. This version was translated into Latin by the time of the council of Vannes (465), which condemned its use. The Latin version was subsequently revised to render it more acceptable to ecclesiastical authorities. This Latin version survives in numerous manuscripts from the early 9th century through the 16th, as well as in Old Occitan and Old French translations. Beginning in the 13th century, the text was sometimes known as the Sortes Apostolorum, a title it shares with at least two other texts.

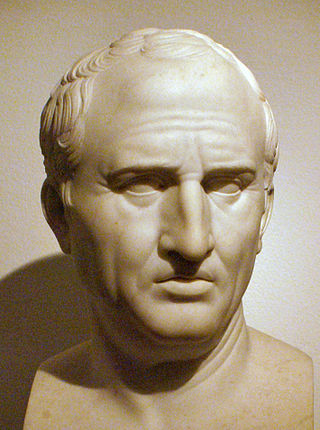

De Divinatione is a philosophical dialogue about ancient Roman divination written in 44 BC by Marcus Tullius Cicero.

The art of memory is any of a number of loosely associated mnemonic principles and techniques used to organize memory impressions, improve recall, and assist in the combination and 'invention' of ideas. An alternative term is "Ars Memorativa" which is also translated as "art of memory" although its more literal meaning is "Memorative Art". It is also referred to as mnemotechnics. It is an 'art' in the Aristotelian sense, which is to say a method or set of prescriptions that adds order and discipline to the pragmatic, natural activities of human beings. It has existed as a recognized group of principles and techniques since at least as early as the middle of the first millennium BCE, and was usually associated with training in rhetoric or logic, but variants of the art were employed in other contexts, particularly the religious and the magical.

There is some evidence that, in addition to being a writing system, runes historically served purposes of magic. This is the case from the earliest epigraphic evidence of the Roman to the Germanic Iron Age, with non-linguistic inscriptions and the alu word. An erilaz appears to have been a person versed in runes, including their magic applications.

Antipater of Tarsus was a Stoic philosopher. He was the pupil and successor of Diogenes of Babylon as leader of the Stoic school, and was the teacher of Panaetius. He wrote works on the gods and on divination, and in ethics he took a higher moral ground than that of his teacher Diogenes.

The Sortes Homericae, a type of divination by bibliomancy, involved drawing a random sentence or line from the works of Homer to answer a question or to predict the future. In the Roman world it co-existed with the various forms of the sortes, such as the Sortes Virgilianae and their Christian successor the Sortes Sanctorum.

Sortes were a frequent method of divination among the ancient Romans. The method involved the drawing of lots (sortes) to obtain knowledge of future events: in many of the ancient Italian temples, the will of the gods was consulted in this way, as at Praeneste and Caere.

The I Ching or Yi Jing, usually translated Book of Changes or Classic of Changes, is an ancient Chinese divination text that is among the oldest of the Chinese classics. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zhou period (1000–750 BC), the I Ching was transformed over the course of the Warring States and early imperial periods (500–200 BC) into a cosmological text with a series of philosophical commentaries known as the "Ten Wings". After becoming part of the Five Classics in the 2nd century BC, the I Ching was the subject of scholarly commentary and the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of East Asian philosophical thought.

Fangshi were Chinese technical specialists who flourished from the third century BCE to the fifth century CE. English translations of fangshi include alchemist, astrologer, diviner, exorcist, geomancer, doctor, magician, monk, mystic, necromancer, occultist, omenologist, physician, physiognomist, technician, technologist, thaumaturge, and wizard.

The Sortes Vergilianae is a form of divination by bibliomancy in which advice or predictions of the future are sought by interpreting passages from the works of the Roman poet Virgil. The use of Virgil for divination may date to as early as the second century AD, and is part of a wider tradition that associated the poet with magic. The system seems to have been modeled on the ancient Roman sortes as seen in the Sortes Homericae, and later the Sortes Sanctorum.

Greek divination is the divination practiced by ancient Greek culture as it is known from ancient Greek literature, supplemented by epigraphic and pictorial evidence. Divination is a traditional set of methods of consulting divinity to obtain prophecies (theopropia) about specific circumstances defined beforehand. As it is a form of compelling divinity to reveal its will by the application of method, it is, and has been since classical times, considered a type of magic. Cicero condemns it as superstition. It depends on a presumed "sympathy" between the mantic event and the real circumstance, which he denies as contrary to the laws of nature. If there were any sympathy, and the diviner could discover it, then "men may approach very near to the power of gods."

The Gospel of the Lots of Mary is a Coptic writing dating to the fifth or sixth century used for divination or bibliomancy. It contains 37 answers to questions (lots), though the methods for readers to select an answer are unclear. Its production and retrieval sites are unknown, though it may have been written near Antinoë in Upper Egypt, and it may have an earlier Greek edition from the fourth century.

References

- ↑ "Sortilege". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XIX (5th ed.). Edinburgh: Archibald C0nstable & Co. 1817. pp. 475–476.

- ↑ Gumpert, Matthew (2012). The End of Meaning: Studies in Catastrophe. Cambridge Scholars. p. 125. ISBN 9781443839433.

- 1 2 Bennett 1998, p. 41.

- ↑ Shchutskii 1979, p. 232-233.

- 1 2 3 Bennett 1998, p. 42.

- ↑ Cicero 1730, p. 110.

- ↑ Bennett 1998, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Halliday 1913, pp. 217–218.

- ↑ Bolton, H. Carrington (1897). "More Counting-out Rhymes". The Journal of American Folklore. American Folklore Society. 10 (39): 312–313. doi:10.2307/533282. JSTOR 533282.