In physics, an electronvolt, also written electron-volt and electron volt, is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum. When used as a unit of energy, the numerical value of 1 eV in joules is equal to the numerical value of the charge of an electron in coulombs. Under the 2019 revision of the SI, this sets 1 eV equal to the exact value 1.602176634×10−19 J.

In physics, specifically in electromagnetism, the Lorentz force law is the combination of electric and magnetic force on a point charge due to electromagnetic fields. The Lorentz force, on the other hand, is a physical effect that occurs in the vicinity of electrically neutral, current-carrying conductors causing moving electrical charges to experience a magnetic force.

A magnetic field is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to the magnetic field. A permanent magnet's magnetic field pulls on ferromagnetic materials such as iron, and attracts or repels other magnets. In addition, a nonuniform magnetic field exerts minuscule forces on "nonmagnetic" materials by three other magnetic effects: paramagnetism, diamagnetism, and antiferromagnetism, although these forces are usually so small they can only be detected by laboratory equipment. Magnetic fields surround magnetized materials, electric currents, and electric fields varying in time. Since both strength and direction of a magnetic field may vary with location, it is described mathematically by a function assigning a vector to each point of space, called a vector field.

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. A cyclotron accelerates charged particles outwards from the center of a flat cylindrical vacuum chamber along a spiral path. The particles are held to a spiral trajectory by a static magnetic field and accelerated by a rapidly varying electric field. Lawrence was awarded the 1939 Nobel Prize in Physics for this invention.

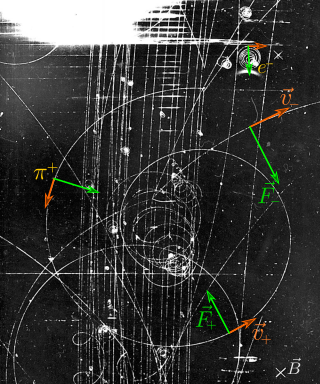

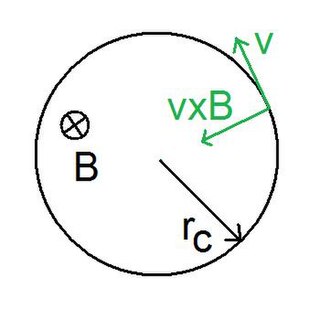

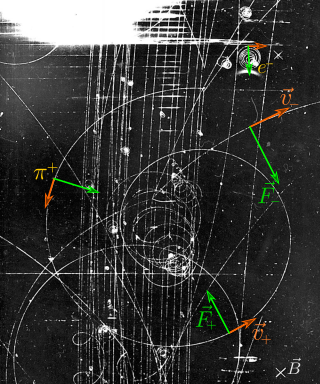

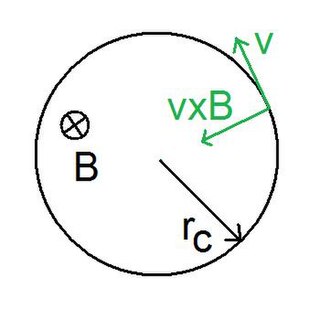

In particle physics, cyclotron radiation is electromagnetic radiation emitted by non-relativistic accelerating charged particles deflected by a magnetic field. The Lorentz force on the particles acts perpendicular to both the magnetic field lines and the particles' motion through them, creating an acceleration of charged particles that causes them to emit radiation as a result of the acceleration they undergo as they spiral around the lines of the magnetic field.

Synchrotron radiation is the electromagnetic radiation emitted when relativistic charged particles are subject to an acceleration perpendicular to their velocity. It is produced artificially in some types of particle accelerators or naturally by fast electrons moving through magnetic fields. The radiation produced in this way has a characteristic polarization, and the frequencies generated can range over a large portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

In electromagnetism, the magnetic moment or magnetic dipole moment is the combination of strength and orientation of a magnet or other object or system that exerts a magnetic field. The magnetic dipole moment of an object determines the magnitude of torque the object experiences in a given magnetic field. When the same magnetic field is applied, objects with larger magnetic moments experience larger torques. The strength of this torque depends not only on the magnitude of the magnetic moment but also on its orientation relative to the direction of the magnetic field. Its direction points from the south pole to north pole of the magnet.

Quadrupole magnets, abbreviated as Q-magnets, consist of groups of four magnets laid out so that in the planar multipole expansion of the field, the dipole terms cancel and where the lowest significant terms in the field equations are quadrupole. Quadrupole magnets are useful as they create a magnetic field whose magnitude grows rapidly with the radial distance from its longitudinal axis. This is used in particle beam focusing.

The tesla is the unit of magnetic flux density in the International System of Units (SI).

In atomic physics, the electron magnetic moment, or more specifically the electron magnetic dipole moment, is the magnetic moment of an electron resulting from its intrinsic properties of spin and electric charge. The value of the electron magnetic moment is −9.2847646917(29)×10−24 J⋅T−1. In units of the Bohr magneton (μB), it is −1.00115965218059(13) μB, a value that was measured with a relative accuracy of 1.3×10−13.

In physics, Larmor precession is the precession of the magnetic moment of an object about an external magnetic field. The phenomenon is conceptually similar to the precession of a tilted classical gyroscope in an external torque-exerting gravitational field. Objects with a magnetic moment also have angular momentum and effective internal electric current proportional to their angular momentum; these include electrons, protons, other fermions, many atomic and nuclear systems, as well as classical macroscopic systems. The external magnetic field exerts a torque on the magnetic moment,

In electrodynamics, the Larmor formula is used to calculate the total power radiated by a nonrelativistic point charge as it accelerates. It was first derived by J. J. Larmor in 1897, in the context of the wave theory of light.

Radiation damping in accelerator physics is a phenomenum where betatron oscillations and longitudinal oscilations of the particle are damped due to energy loss by synchrotron radiation. It can be used to reduce the beam emittance of a high-velocity charged particle beam.

Electron scattering occurs when electrons are displaced from their original trajectory. This is due to the electrostatic forces within matter interaction or, if an external magnetic field is present, the electron may be deflected by the Lorentz force. This scattering typically happens with solids such as metals, semiconductors and insulators; and is a limiting factor in integrated circuits and transistors.

The mass-to-charge ratio (m/Q) is a physical quantity relating the mass (quantity of matter) and the electric charge of a given particle, expressed in units of kilograms per coulomb (kg/C). It is most widely used in the electrodynamics of charged particles, e.g. in electron optics and ion optics.

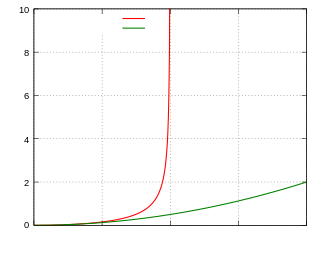

The gyroradius is the radius of the circular motion of a charged particle in the presence of a uniform magnetic field. In SI units, the non-relativistic gyroradius is given by where is the mass of the particle, is the component of the velocity perpendicular to the direction of the magnetic field, is the electric charge of the particle, and is the magnetic field flux density.

Cyclotron resonance describes the interaction of external forces with charged particles experiencing a magnetic field, thus moving on a circular path. It is named after the cyclotron, a cyclic particle accelerator that utilizes an oscillating electric field tuned to this resonance to add kinetic energy to charged particles.

In physics, relativistic quantum mechanics (RQM) is any Poincaré covariant formulation of quantum mechanics (QM). This theory is applicable to massive particles propagating at all velocities up to those comparable to the speed of light c, and can accommodate massless particles. The theory has application in high energy physics, particle physics and accelerator physics, as well as atomic physics, chemistry and condensed matter physics. Non-relativistic quantum mechanics refers to the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics applied in the context of Galilean relativity, more specifically quantizing the equations of classical mechanics by replacing dynamical variables by operators. Relativistic quantum mechanics (RQM) is quantum mechanics applied with special relativity. Although the earlier formulations, like the Schrödinger picture and Heisenberg picture were originally formulated in a non-relativistic background, a few of them also work with special relativity.

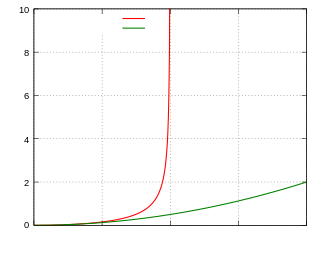

Tests of relativistic energy and momentum are aimed at measuring the relativistic expressions for energy, momentum, and mass. According to special relativity, the properties of particles moving approximately at the speed of light significantly deviate from the predictions of Newtonian mechanics. For instance, the speed of light cannot be reached by massive particles.

This glossary of physics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to physics, its sub-disciplines, and related fields, including mechanics, materials science, nuclear physics, particle physics, and thermodynamics. For more inclusive glossaries concerning related fields of science and technology, see Glossary of chemistry terms, Glossary of astronomy, Glossary of areas of mathematics, and Glossary of engineering.