In metalworking and jewelry making, casting is a process in which a liquid metal is delivered into a mold that contains a negative impression of the intended shape. The metal is poured into the mold through a hollow channel called a sprue. The metal and mold are then cooled, and the metal part is extracted. Casting is most often used for making complex shapes that would be difficult or uneconomical to make by other methods.

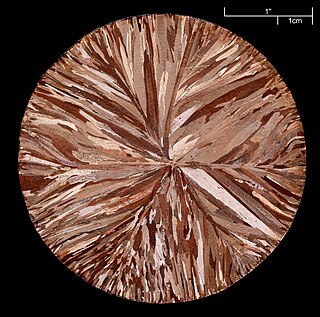

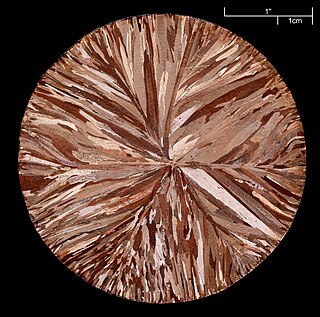

An ingot is a piece of relatively pure material, usually metal, that is cast into a shape suitable for further processing. In steelmaking, it is the first step among semi-finished casting products. Ingots usually require a second procedure of shaping, such as cold/hot working, cutting, or milling to produce a useful final product. Non-metallic and semiconductor materials prepared in bulk form may also be referred to as ingots, particularly when cast by mold based methods. Precious metal ingots can be used as currency, or as a currency reserve, as with gold bars.

Die casting is a metal casting process that is characterized by forcing molten metal under high pressure into a mold cavity. The mold cavity is created using two hardened tool steel dies which have been machined into shape and work similarly to an injection mold during the process. Most die castings are made from non-ferrous metals, specifically zinc, copper, aluminium, magnesium, lead, pewter, and tin-based alloys. Depending on the type of metal being cast, a hot- or cold-chamber machine is used.

Sand casting, also known as sand molded casting, is a metal casting process characterized by using sand as the mold material. The term "sand casting" can also refer to an object produced via the sand casting process. Sand castings are produced in specialized factories called foundries. Over 60% of all metal castings are produced via sand casting process.

Lost-foam casting (LFC) is a type of evaporative-pattern casting process that is similar to investment casting except foam is used for the pattern instead of wax. This process takes advantage of the low boiling point of polymer foams to simplify the investment casting process by removing the need to melt the wax out of the mold.

A sprue is the vertical passage through which liquid material is introduced into a mold and it is a large diameter channel through which the material enters the mold. It connects the pouring basin to the runner. In many cases it controls the flow of material into the mold. During casting or molding, the material in the sprue will solidify and need to be removed from the finished part. It is usually tapered downwards to minimize turbulence and formation of air bubbles.

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals processed are aluminum and cast iron. However, other metals, such as bronze, brass, steel, magnesium, and zinc, are also used to produce castings in foundries. In this process, parts of desired shapes and sizes can be formed.

Continuous casting, also called strand casting, is the process whereby molten metal is solidified into a "semifinished" billet, bloom, or slab for subsequent rolling in the finishing mills. Prior to the introduction of continuous casting in the 1950s, steel was poured into stationary molds to form ingots. Since then, "continuous casting" has evolved to achieve improved yield, quality, productivity and cost efficiency. It allows lower-cost production of metal sections with better quality, due to the inherently lower costs of continuous, standardised production of a product, as well as providing increased control over the process through automation. This process is used most frequently to cast steel. Aluminium and copper are also continuously cast.

Investment casting is an industrial process based on lost-wax casting, one of the oldest known metal-forming techniques. The term "lost-wax casting" can also refer to modern investment casting processes.

Chvorinov's rule is an applied physics relationship first expressed by Czech engineer Nicolas Chvorinov in 1940, that relates the solidification time for a simple casting to the volume and surface area of the casting.

In casting, a pattern is a replica of the object to be cast, used to prepare the cavity into which molten material will be poured during the casting process.

A chill is an object used to promote solidification in a specific portion of a metal casting mold. Normally the metal in the mould cools at a certain rate relative to thickness of the casting. When the geometry of the molding cavity prevents directional solidification from occurring naturally, a chill can be strategically placed to help promote it. There are two types of chills: internal and external chills.

Directional solidification(DS) and progressive solidification are types of solidification within castings. Directional solidification is solidification that occurs from farthest end of the casting and works its way towards the sprue. Progressive solidification, also known as parallel solidification, is solidification that starts at the walls of the casting and progresses perpendicularly from that surface.

Permanent mold casting is a metal casting process that employs reusable molds, usually made from metal. The most common process uses gravity to fill the mold, however gas pressure or a vacuum are also used. A variation on the typical gravity casting process, called slush casting, produces hollow castings. Common casting metals are aluminium, magnesium, and copper alloys. Other materials include tin, zinc, and lead alloys and iron and steel are also cast in graphite molds.

Full-mold casting is an evaporative-pattern casting process which is a combination of sand casting and lost-foam casting. It uses an expanded polystyrene foam pattern which is then surrounded by sand, much like sand casting. The metal is then poured directly into the mold, which vaporizes the foam upon contact.

Plaster mold casting is a metalworking casting process similar to sand casting except the molding material is plaster of Paris instead of sand. Like sand casting, plaster mold casting is an expendable mold process, however it can only be used with non-ferrous materials. It is used for castings as small as 30 g (1 oz) to as large as 7–10 kg (15–22 lb). Generally, the form takes less than a week to prepare. Production rates of 1–10 units/hr can be achieved with plaster molds.

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a casting, which is ejected or broken out of the mold to complete the process. Casting materials are usually metals or various time setting materials that cure after mixing two or more components together; examples are epoxy, concrete, plaster and clay. Casting is most often used for making complex shapes that would be otherwise difficult or uneconomical to make by other methods. Heavy equipment like machine tool beds, ships' propellers, etc. can be cast easily in the required size, rather than fabricating by joining several small pieces. Casting is a 7,000-year-old process. The oldest surviving casting is a copper frog from 3200 BC.

Shell molding, also known as shell-mold casting, is an expendable mold casting process that uses resin covered sand to form the mold. As compared to sand casting, this process has better dimensional accuracy, a higher productivity rate, and lower labour requirements. It is used for small to medium parts that require high precision. Shell molding was developed as a manufacturing process during the mid-20th century in Germany. It was invented by German engineer Johannes Croning. Shell mold casting is a metal casting process similar to sand casting, in that molten metal is poured into an expendable mold. However, in shell mold casting, the mold is a thin-walled shell created from applying a sand-resin mixture around a pattern. The pattern, a metal piece in the shape of the desired part, is reused to form multiple shell molds. A reusable pattern allows for higher production rates, while the disposable molds enable complex geometries to be cast. Shell mold casting requires the use of a metal pattern, oven, sand-resin mixture, dump box, and molten metal.

A core is a device used in casting and moulding processes to produce internal cavities and reentrant angles. The core is normally a disposable item that is destroyed to get it out of the piece. They are most commonly used in sand casting, but are also used in die casting and injection moulding.

A casting defect is an undesired irregularity in a metal casting process. Some defects can be tolerated while others can be repaired, otherwise they must be eliminated. They are broken down into five main categories: gas porosity, shrinkage defects, mould material defects, pouring metal defects, and metallurgical defects.