Related Research Articles

Gregor Florian Gysi is a German attorney, former president of the Party of the European Left and a prominent politician of The Left political party.

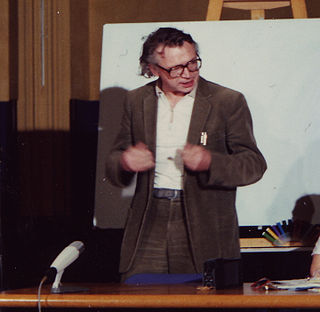

Rudolf Bahro was a dissident from East Germany who, since his death, has been recognised as a philosopher, political figure and author. Bahro was a leader of the West German party The Greens, but became disenchanted with its political organization, left the party and explored spiritual approaches to sustainability.

Volker Braun is a German writer. His works include Provokation für mich – a collection of poems written between 1959 and 1964 and published in 1965, a play, Die Kipper, and Das ungezwungene Leben Kasts (1972).

Hilde Benjamin was an East German judge and Minister of Justice of the German Democratic Republic. She is most notorious for presiding over the East German show trials of the 1950s, which drew comparisons to the Nazi Party's Volksgericht show trials under Judge Roland Freisler. Hilde Benjamin is particularly known for being responsible for the politically motivated prosecution of Erna Dorn and Ernst Jennrich. In his 1994 inauguration speech German President Roman Herzog cited Hilde Benjamin as a symbol of totalitarianism and injustice, and called both her name and legacy incompatible with the German Constitution and with the rule of law.

Hubertus Knabe is a German historian and was the scientific director of the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial, a museum and memorial in a notorious former Stasi torture prison in Berlin. Knabe is noted for several works on oppression in the former Communist states of Eastern Europe, particularly in East Germany. He became involved with green politics, and was active in the Alliance '90/The Greens.

Arnold Angelus Schölzel is a German editor and former defector, currently the editor-in-chief of the far-left newspaper Junge Welt. Prior to 1989, Schölzel worked at Humboldt University in East Berlin, and also was an informant for the East German domestic intelligence agency, the Stasi.

Zersetzung was a psychological warfare technique used by the Ministry for State Security (Stasi) to repress political opponents in East Germany during the 1970s and 1980s. Zersetzung served to combat alleged and actual dissidents through covert means, using secret methods of abusive control and psychological manipulation to prevent anti-government activities. People were commonly targeted on a pre-emptive and preventive basis, to limit or stop activities of dissent that they may have gone on to perform, and not on the basis of crimes they had actually committed. Zersetzung methods were designed to break down, undermine, and paralyze people behind "a facade of social normality" in a form of "silent repression".

Ernst Melsheimer was a German lawyer.

Helmut Müller-Enbergs is a German political scientist who has written extensively on the Stasi and related aspects of the German Democratic Republic's history.

An unofficial collaborator or IM, or euphemistically informal collaborator, was an informant in the German Democratic Republic who delivered private information to the Ministry for State Security. At the end of the East German government, there was a network of around 189,000 informants, working at every level of society.

Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk is a German historian and author. His work is focused on the German Democratic Republic and its Ministry for State Security.

Karl Wilhelm Fricke is a German political journalist and author. He has produced several of the standard works on resistance and state repression in the German Democratic Republic (1949–1990). In 1955, he became one of several hundred kidnap victims of the East German Ministry for State Security, captured in West Berlin and taken to the east where for nearly five years he was held in state detention.

Bernd Eisenfeld, also known by the pseudonym Fred Werner, was an opponent of the East German dictatorship who became a writer and an historian.

Ehrhart Neubert is a retired German Evangelical minister and theologian.

Marlies Deneke is a German politician.

Katja Havemann is a German civil rights activist and author.

Jutta Braband is a former German politician. In the German Democratic Republic she was a civil rights activist who after 1990 became a PDS member of the Germany parliament (Bundestag). Her parliamentary career ended in May 1992 after it had become known that fifteen years earlier she had worked for the Ministry for State Security (Stasi) as a registered informant .

Christa Luft is a German economist and politician of the SED/PDS. Luft joined the SED in 1958. From 18 November 1989 to 18 March 1990, she was the Minister of Economics in the Modrow government. From 1994 to 2002 she was member of the Bundestag for the PDS.

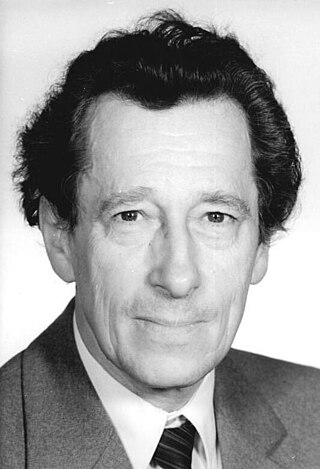

Gerhard Riege was a respected East German law professor.

Hanns Leske is a German sports historian, political scientist and former Berlin local politician.

References

- ↑ "Rolf Henrich geb. 1944". Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn. 4 December 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Helmut Müller-Enbergs; Jan Wielgohs. "Henrich, Rolf * 24.2.1944 Dissident". Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur: Biographische Datenbanken. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- 1 2 Rolf Henrich (1989). Der vormundschaftliche Staat: Vom Versagen des real existierenden Sozialismus. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3499125362.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk. "Rolf Henrich". Robert-Havemann-Gesellschaft e.V., Berlin. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Die Wahrheit öffentlich machen Ein früherer Parteisekretär rechnet mit dem SED-System ab Der SED steht, rechtzeitig zur 40-Jahr-Feier der DDR, ein neuer Dissident ins Haus. Elf Jahre nach Bahro klagt ein Genosse die Parteiführung öffentlich an, sie halte sich nur mit Hilfe eines brutalen und allgegenwärtigen Polizeiapparates an der Macht, die Stasi sei "der Garant der Sozialversicherung" für die Gerontokraten im Politbüro". Der Spiegel (online). 27 March 1989. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "[ich war]...begeisterter FDJler...Ich war damals sogar ein bißchen fanatisch.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gundula Mieke (8 September 2014). "Meine Wende: Rolf Henrich "Stell dich auf die Seite derer, auf die alle mit dem Finger zeigen"". Berliner Kurier . Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Rolf Henrich: Jurist". Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland , Bonn . Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Adelbert Reif [in German] (9 November 2009). "Der Despot war nur noch ein Phantom: Der Regimekritiker und Anwalt Rolf Henrich über den Niedergang des SED-Regimes und die Frage, warum die DDR kein Rechtsstaat war". Berliner Zeitung (online). Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Marlies Menge [in German] (7 April 1989). "Anders als Bahro: Ein Buch brachte dem DDR-Anwalt Rolf Henrich Berufsverbot ein". Die Zeit. Die Zeit (online). Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "Ich mußte mich erst langsam aus dem Dogmatismus befreien, das war ein mühsamer Prozeß innerer Auseinandersetzung."

- ↑ "Das trifft den Parteiapparat ins Herz. Ein SED-Funktionär kritisiert den DDR-Sozialismus" [That's gonna hit the heart of the party. An SED functionary criticises GDR socialism.] (in German). Der Spiegel (online). 22 August 1977. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "Ende der DDR: Gorbatschow war an Stasi-Übernahme durch KGB interessiert: Skurriles vom Untergang der DDR: Nach SPIEGEL-Informationen wollte Michail Gorbatschow im Jahr 1990, dass der KGB die Auslandsspionage der Stasi und das gesamte IM-Netz übernimmt. Die sowjetische Bestandsgarantie für die DDR hat der damalige Kreml-Chef schon vor dem Untergang des Landes widerrufen". Der Spiegel (online). 10 October 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2015.