Related Research Articles

Louis the Pious, also called the Fair and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aquitaine from 781. As the only surviving son of Charlemagne and Hildegard, he became the sole ruler of the Franks after his father's death in 814, a position that he held until his death except from November 833 to March 834, when he was deposed.

Charles the Bald, also known as Charles II, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), King of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a series of civil wars during the reign of his father, Louis the Pious, Charles succeeded, by the Treaty of Verdun (843), in acquiring the western third of the empire. He was a grandson of Charlemagne and the youngest son of Louis the Pious by his second wife, Judith.

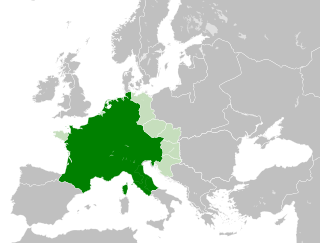

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lombards in Italy from 774. In 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III in an effort to transfer the status of Roman Empire from the Byzantine Empire to Western Europe. The Carolingian Empire is sometimes considered the first phase in the history of the Holy Roman Empire.

Austrasia was the northeastern kingdom within the core of the Frankish empire during the Early Middle Ages, centring on the Meuse, Middle Rhine and the Moselle rivers. It included the original Frankish-ruled territories within what had been the northernmost part of Roman Gaul, and cities such as Cologne, Trier and Metz. It also stretched beyond the old Roman borders on the Rhine into Frankish areas which had never been formally under Roman rule. It came into being as a part of the Frankish Empire founded by Clovis I (481–511). At the same time, the initial powerbase of Clovis himself was the more Romanized part of northern Gaul, lying southwest of Austrasia, which came to be known as Neustria.

Neustria was the western part of the Kingdom of the Franks during the Early Middle Ages, in contrast to the eastern Frankish kingdom, Austrasia. It initially included land between the Loire and the Silva Carbonaria, in the north of present-day France, with Paris, Orléans, Tours, Soissons as its main cities.

The Kingdom of the Franks, also known as the Frankish Kingdom, the Frankish Empire or Francia, was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Frankish Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties during the Early Middle Ages. Francia was among the last surviving Germanic kingdoms from the Migration Period era.

The Chancellor of France, also known as the Grand Chancellor or Lord Chancellor, was the officer of state responsible for the judiciary of the Kingdom of France. The Chancellor was responsible for seeing that royal decrees were enrolled and registered by the sundry parlements, provincial appellate courts. However, since the Chancellor was appointed for life, and might fall from favour, or be too ill to carry out his duties, his duties would occasionally fall to his deputy, the Keeper of the Seals of France.

Sigebert III was the Merovingian king of Austrasia from 633 to his death around 656. He was described as the first Merovingian roi fainéant —do-nothing king—, in effect the mayor of the palace ruling the kingdom throughout his reign. However he lived a pious Christian life and was later sanctified, being remembered as Saint Sigebert of Austrasia in the Roman Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church.

Pepin or Pippin, was King of Italy from 781 until his death in 810. He was the third son of Charlemagne. Upon his baptism in 781, Carloman was renamed Pepin, where he was also crowned as king of the Lombard Kingdom his father had conquered. Pepin ruled the kingdom from a young age under Charlemagne, but predeceased his father. His son Bernard was named king of Italy after him, and his descendants were the longest-surviving direct male line of the Carolingian dynasty.

Adalard of Corbie was the son of Bernard who was the son of Charles Martel and half-brother of Pepin; Charlemagne was his cousin. He is recognised as a saint within the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Church.

The Capitulary of Quierzy was a capitulary of Emperor Charles II that had a series of measures to safeguard the administration of his realm during his second Italian expedition, as well as directions for his son Louis the Stammerer, who was entrusted with the government during his father's absence. It has traditionally been seen as the basis on which the major vassals of the kingdom of France such as the counts of Flanders, were enabled to become more independent.

Ermengardeof Hesbaye, probably a member of the Robertian dynasty, was Carolingian empress from 813 and Queen of the Franks from 814 until her death as the wife of the Carolingian emperor Louis the Pious.

A capitulary was a series of legislative or administrative acts emanating from the Frankish court of the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties, especially that of Charlemagne, the first emperor of the Romans in the west since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century. They were so called because they were formally divided into sections called capitula.

Pepin I or Pepin I of Aquitaine was King of Aquitaine and Duke of Maine.

Quierzy, also known as Quierzy-sur-Oise, is a commune in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France in northern France, straddling the Oise River between Noyon and Chauny.

Wala was a son of Bernard, son of Charles Martel, and one of the principal advisers of his cousin Charlemagne, of Charlemagne's son Louis the Pious, and of Louis's son Lothair I. He succeeded his brother Adalard as abbot of Corbie and its new daughter foundation, Corvey, in 826 or 827. His feast day is 31 August

Engelram was Chamberlain to Charles the Bald through sometime after 871. He also held the title of count from 853, but it is unclear what his domain was. Nothing is known about his ancestry.

The Capitulary of Servais was the implementation of an agreement between Charles the Bald and his half-brother Lothar to maintain the peace. In a conference of Charles and Lothar at Valenciennes in 853, the missi [literally, the sent ones] were re-established after a long hiatus. Lothar recommended that peace and justice be secured by sending out missi to enforce the laws and help keep the peace. The Diet of Servais confirmed the decisions arrived at during the conference. The Capitulary of Servais was enacted by Charles in November 853 dividing the Franco-Burgundian portion of Charles’ realm into twelve districts (missatica) to enforce the measures of this agreement. According to Nelson, the twelve missicati and associated missi were:

References

- ↑ Previte-Orton, C. W., ed. (1952). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 155.

- ↑ Nelson, Janet (1992). Charles the Bald. London: Longman Press. pp. 43–50.

- ↑ Nelson, Janet L. (Translator) (1991). The Annals of St-Bertin. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 188–189.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ↑ Nelson, Janet L. (1992). Charles the Bald. London: Longman. p. 265.

- ↑ Bury, J. B., ed. (1924). The Cambridge Medieval History, Volume III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 11.

- ↑ Nelson, Janet L. (1992). Charles the Bald. London: Longman Press. p. 265.