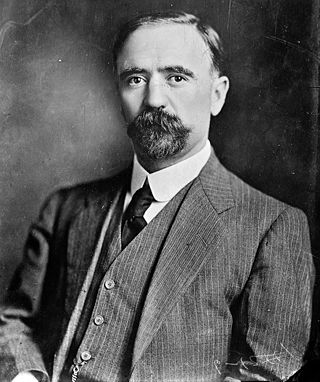

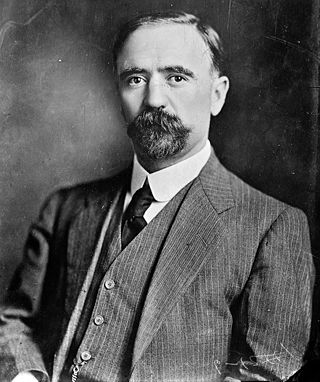

Francisco Ignacio Madero González was a Mexican businessman, revolutionary, writer and statesman, who served as the 37th president of Mexico from 1911 until he was deposed in a coup d'état in February 1913 and assassinated. He came to prominence as an advocate for democracy and as an opponent of President and de facto dictator Porfirio Díaz. After Díaz claimed to have won the fraudulent election of 1910 despite promising a return to democracy, Madero started the Mexican Revolution to oust Díaz. The Mexican revolution would continue until 1920, well after Madero and Díaz's deaths, with hundreds of thousands dead.

Francisco "Pancho" Villa was a Mexican revolutionary and general in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key figure in the revolutionary movement that forced out President Porfirio Díaz and brought Francisco I. Madero to power in 1911. When Madero was ousted by a coup led by General Victoriano Huerta in February 1913, Villa joined the anti-Huerta forces in the Constitutionalist Army led by Venustiano Carranza. After the defeat and exile of Huerta in July 1914, Villa broke with Carranza. Villa dominated the meeting of revolutionary generals that excluded Carranza and helped create a coalition government. Emiliano Zapata and Villa became formal allies in this period. Like Zapata, Villa was strongly in favor of land reform, but did not implement it when he had power. At the height of his power and popularity in late 1914 and early 1915, the U.S. considered recognizing Villa as Mexico's legitimate authority.

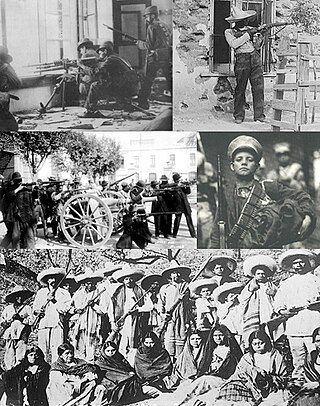

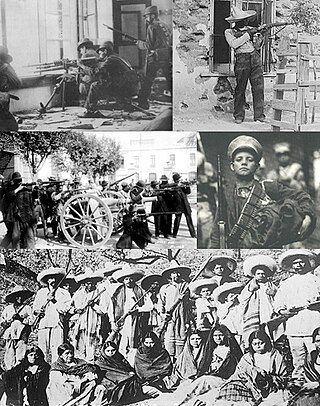

The Mexican Revolution was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history" and resulted in the destruction of the Federal Army, its replacement by a revolutionary army, and the transformation of Mexican culture and government. The northern Constitutionalist faction prevailed on the battlefield and drafted the present-day Constitution of Mexico, which aimed to create a strong central government. Revolutionary generals held power from 1920 to 1940. The revolutionary conflict was primarily a civil war, but foreign powers, having important economic and strategic interests in Mexico, figured in the outcome of Mexico's power struggles; the U.S. involvement was particularly high. The conflict led to the deaths of around one million people, mostly noncombatants.

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero with the aid of other Mexican generals and the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico. His violent seizure of power set off a new wave of armed conflict in the Mexican Revolution.

Pascual Orozco Vázquez, Jr. was a Mexican revolutionary leader who rose up to support Francisco I. Madero in late 1910 to depose long-time president Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911). Orozco was a natural military leader whose victory over the Federal Army at Ciudad Juárez was a key factor in forcing Díaz to resign in May 1911. Following Díaz's resignation and the democratic election of Madero in November 1911, Orozco served Madero as leader of the state militia in Chihuahua, a paltry reward for his service in the Mexican Revolution. Orozco revolted against the Madero government 16 months later, issuing the Plan Orozquista in March 1912. It was a serious revolt which the Federal Army struggled to suppress. When Victoriano Huerta led a coup d'état against Madero in February 1913 during which Madero was murdered, Orozco joined the Huerta regime. Orozco's revolt against Madero somewhat tarnished his revolutionary reputation, but his subsequent support of Huerta compounded the repugnance against him.

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza was a Mexican land owner and politician who served as President of Mexico from 1917 until his assassination in 1920, during the Mexican Revolution. He was previously Mexico's de facto head of state as Primer Jefe of the Constitutionalist faction from 1914 to 1917, and previously served as a senator and governor for Coahuila. He played the leading role in drafting the Constitution of 1917 and maintained Mexican neutrality in World War I.

Francisco León de la Barra y Quijano was a Mexican political figure and diplomat who served as the 36th President of Mexico from May 25 to November 6, 1911 during the Mexican Revolution, following the resignations of President Porfirio Díaz and Vice President Ramón Corral. He previously served as Secretary of Foreign Affairs for one month during the Díaz administration and again from 1913 to 1914 under President Victoriano Huerta. He was known to conservatives as "The White President" or the "Pure President."

The Liberation Army of the South was a guerrilla force led for most of its existence by Emiliano Zapata that took part in the Mexican Revolution from 1911 to 1920. During that time, the Zapatistas fought against the national governments of Porfirio Díaz, Francisco Madero, Victoriano Huerta, and Venustiano Carranza. Their goal was rural land reform, specifically reclaiming communal lands stolen by hacendados in the period before the revolution. Although rarely active outside their base in Morelos, they allied with Pancho Villa to support the Conventionists against the Carrancistas. After Villa's defeat, the Zapatistas remained in open rebellion. It was only after Zapata's 1919 assassination and the overthrow of the Carranza government that Zapata's successor, Gildardo Magaña, negotiated peace with President Álvaro Obregón.

Félix Díaz Prieto was a Mexican politician and general born in Oaxaca, Oaxaca. He was a leading figure in the rebellion against President Francisco I. Madero during the Mexican Revolution. He was the nephew of president Porfirio Díaz.

The Mexican Army is the combined land and air branch and is the largest part of the Mexican Armed Forces; it is also known as the National Defense Army.

The military history of Mexico encompasses armed conflicts within that nation's territory, dating from before the arrival of Europeans in 1519 to the present era. Mexican military history is replete with small-scale revolts, foreign invasions, civil wars, indigenous uprisings, and coups d'état by disgruntled military leaders. Mexico's colonial-era military was not established until the eighteenth century. After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in the early sixteenth century, the Spanish crown did not establish on a standing military, but the crown responded to the external threat of a British invasion by creating a standing military for the first time following the Seven Years' War (1756–63). The regular army units and militias had a short history when in the early 19th century, the unstable situation in Spain with the Napoleonic invasion gave rise to an insurgency for independence, propelled by militarily untrained men fighting for the independence of Mexico. The Mexican War of Independence (1810–21) saw royalist and insurgent armies battling to a stalemate in 1820. That stalemate ended with the royalist military officer turned insurgent, Agustín de Iturbide persuading the guerrilla leader of the insurgency, Vicente Guerrero, to join in a unified movement for independence, forming the Army of the Three Guarantees. The royalist military had to decide whether to support newly independent Mexico. With the collapse of the Spanish state and the establishment of first a monarchy under Iturbide and then a republic, the state was a weak institution. The Roman Catholic Church and the military weathered independence better. Military men dominated Mexico's nineteenth-century history, most particularly General Antonio López de Santa Anna, under whom the Mexican military were defeated by Texas insurgents for independence in 1836 and then the U.S. invasion of Mexico (1846–48). With the overthrow of Santa Anna in 1855 and the installation of a government of political liberals, Mexico briefly had civilian heads of state. The Liberal Reforms that were instituted by Benito Juárez sought to curtail the power of the military and the church and wrote a new constitution in 1857 enshrining these principles. Conservatives comprised large landowners, the Catholic Church, and most of the regular army revolted against the Liberals, fighting a civil war. The Conservative military lost on the battlefield. But Conservatives sought another solution, supporting the French intervention in Mexico (1862–65). The Mexican army loyal to the liberal republic were unable to stop the French army's invasion, briefly halting it with a victory at Puebla on 5 May 1862. Mexican Conservatives supported the installation of Maximilian Hapsburg as Emperor of Mexico, propped up by the French and Mexican armies. With the military aid of the U.S. flowing to the republican government in exile of Juárez, the French withdrew its military supporting the monarchy and Maximilian was caught and executed. The Mexican army that emerged in the wake of the French Intervention was young and battle tested, not part of the military tradition dating to the colonial and early independence eras.

The Mexican Federal Army, also known as the Federales in popular culture, was the military of Mexico from 1876 to 1914 during the Porfiriato, the long rule of President Porfirio Díaz, and during the presidencies of Francisco I. Madero and Victoriano Huerta. Under President Díaz, a military hero against the French Intervention in Mexico, the Federal Army was composed of senior officers who had served in long ago conflicts. At the time of the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution most were old men and incapable of leading men on the battlefield. When the rebellions broke out against Díaz following fraudulent elections of 1910, the Federal Army was incapable of responding. Although revolutionary fighters helped bring Francisco I. Madero to power, Madero retained the Federal Army rather than the revolutionaries. Madero used the Federal Army to suppress rebellions against his government by Pascual Orozco and Emiliano Zapata. Madero placed General Victoriano Huerta as interim commander of the military during the Ten Tragic Days of February 1913 to defend his government. Huerta changed sides and ousted Madero's government. Rebellions broke out against Huerta's regime. When revolutionary armies succeeded in ousting Huerta in July 1914, the Federal Army ceased to exist as an entity, with the signing of the Teoloyucan Treaties.

The United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution was varied and seemingly contradictory, first supporting and then repudiating Mexican regimes during the period 1910–1920. For both economic and political reasons, the U.S. government generally supported those who occupied the seats of power, but could withhold official recognition. The U.S. supported the regime of Porfirio Díaz after initially withholding recognition since he came to power by coup. In 1909, Díaz and U.S. President Taft met in Ciudad Juárez, across the border from El Paso, Texas. Prior to Woodrow Wilson's inauguration on March 4, 1913, the U.S. Government focused on just warning the Mexican military that decisive action from the U.S. military would take place if lives and property of U.S. nationals living in the country were endangered. President William Howard Taft sent more troops to the US-Mexico border but did not allow them to intervene directly in the conflict, a move which Congress opposed. Twice during the Revolution, the U.S. sent troops into Mexico, to occupy Veracruz in 1914 and to northern Mexico in 1916 in a failed attempt to capture Pancho Villa. U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America was to assume the region was the sphere of influence of the U.S., articulated in the Monroe Doctrine. However the U.S. role in the Mexican Revolution has been exaggerated. It did not directly intervene in the Mexican Revolution in a sustained manner.

Federales is a Spanish term used in an informal context to denote security forces operating under a federal political system. The term gained widespread usage by English speakers due to popularization in such films as The Wild Bunch, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Blue Streak, the television drama series Breaking Bad and its spinoff prequel Better Call Saul, as well as the song Pancho and Lefty by Townes Van Zandt. The term is a cognate and counterpart to the slang "Feds" in the United States.

The Ten Tragic Days during the Mexican Revolution is the name given to the multi-day coup d'état in Mexico City by opponents of Francisco I. Madero, the democratically elected president of Mexico, between 9–19 February 1913. It instigated a second phase of the Mexican Revolution, after dictator Porfirio Díaz had been ousted and replaced in elections by Francisco I. Madero. The coup was carried out by general Victoriano Huerta and supporters of the old regime, with support from the United States.

The Battle of Zacatecas, also known as the Toma de Zacatecas, was the bloodiest battle in the campaign to overthrow Mexican President Victoriano Huerta. On June 23, 1914, Pancho Villa's División del Norte decisively defeated the federal troops of General Luis Medina Barrón defending the town of Zacatecas. The great victory demoralized Huerta's supporters, leading to his resignation on July 15. However, the Toma de Zacatecas also marked the end of support of Villa's Division of the North from Constitutionalist leader Venustiano Carranza and US President Woodrow Wilson.

The Treaty of Ciudad Juárez was a peace treaty signed between the President of Mexico, Porfirio Díaz, and the revolutionary Francisco Madero on May 21, 1911. The treaty put an end to the fighting between forces supporting Madero and those of Díaz and thus concluded the initial phase of the Mexican Revolution.

The First Battle of Ciudad Juárez took place in April and May 1911 between federal forces loyal to President Porfirio Díaz and rebel forces of Francisco Madero, during the Mexican Revolution. Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa commanded Madero's army, which besieged Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. After two days of fighting the city's garrison surrendered and Orozco and Villa took control of the town. The fall of Ciudad Juárez to Madero, combined with Emiliano Zapata's taking of Cuautla in Morelos, convinced Díaz that he could not hope to defeat the rebels. As a result, he agreed to the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez, resigned and went into exile in France, thus ending the initial stage of the Mexican Revolution.

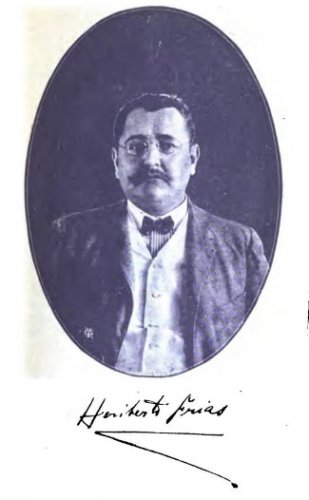

The Tomochic Rebellion was a violent confrontation between rural villagers and the army of the Mexican Government from 1891- 1892 in the town of Tomochi, a small rural town in the mountainous Guerrero district of the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Led by Cruz Chavez, a notable local and charismatic figure, the rebellion was one of a series of uprisings against the government calling for social reform and religious autonomy. The rebellion initially met with success but was eventually crushed by government forces in 1892. The defiance of the tomochitecos became a symbol of resistance against tyranny and became enshrined in Mexican folklore. Furthermore, the rebellion was unique as it was one of the first religiously inspired revolts against the state, with the rebels rallying behind the cult of Teresa Urrea as a symbol of their defiance of the regime.