Related Research Articles

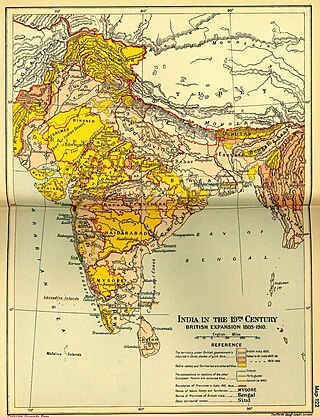

Company rule in India was the rule of the British East India Company on the Indian subcontinent. This is variously taken to have commenced in 1757, after the Battle of Plassey, when the Nawab of Bengal Siraj ud-Daulah was defeated and replaced with Mir Jafar, who had the support of the East India Company; or in 1765, when the Company was granted the diwani, or the right to collect revenue, in Bengal and Bihar; or in 1773, when the Company abolished local rule (Nizamat) in Bengal and established a capital in Calcutta, appointed its first Governor-General of Fort William, Warren Hastings, and became directly involved in governance. The East India Company significantly expanded its influence throughout the Indian subcontinent after the Anglo-Mysore Wars, Anglo-Maratha Wars, and Anglo-Sikh Wars. Lord William Bentinck became the first Governor General of India in 1834 under the Government of India Act 1833. The Company India ruled until 1858, when, after the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the Government of India Act 1858, the India Office of the British government assumed the task of directly administering India in the new British Raj.

A zamindar in the Indian subcontinent was an autonomous or semi-autonomous feudal ruler of a zamindari. The term itself came into use during the reign of Mughals, and later the British had begun using it as a native synonym for "estate". The term means landowner in Persian. They were typically hereditary, and held the right to collect tax on behalf of imperial courts or for military purposes.

All India Kisan Sabha, is the peasant or farmers' wing of the Communist Party of India, an important peasant movement formed by Sahajanand Saraswati in 1936.

The Permanent Settlement, also known as the Permanent Settlement of Bengal, was an agreement between the East India Company and landlords of Bengal to fix revenues to be raised from land that had far-reaching consequences for both agricultural methods and productivity in the entire British Empire and the political realities of the Indian countryside. It was concluded in 1793 by the Company administration headed by Charles, Earl Cornwallis. It formed one part of a larger body of legislation, known as the Cornwallis Code. The Cornwallis Code of 1793 divided the East India Company's service personnel into three branches: revenue, judicial, and commercial. Revenues were collected by zamindars, native Indians who were treated as landowners. This division created an Indian landed class that supported British authority.

The ryotwari system was a land revenue system in British India introduced by Thomas Munro, which allowed the government to deal directly with the cultivator ('ryot') for revenue collection and gave the peasant freedom to cede or acquire new land for cultivation.

The Singranatore family is the consanguineous name given to a noble family in Rajshahi of landed aristocracy in erstwhile East Bengal and West Bengal that were prominent in the nineteenth century till the fall of the monarchy in India by Royal Assent in 1947 and subsequently abolished by the newly formed democratic Government of East Pakistan in 1950 by the State Acquisition Act.

Numbardar or Lambardar was the village headman responsible for tax collection in the village during the British Raj. They were appointed under the Mahalwari system.

The Economy of India under Company rule describes the economy of those regions that fell under Company rule in India during the years 1757 to 1858. The British East India Company began ruling parts of the Indian subcontinent beginning with the Battle of Plassey, which led to the conquest of Bengal Subah and the founding of the Bengal Presidency, before the Company expanded across most of the subcontinent up until the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

Zerat is a land ownership system in early colonial India. The zerat system was particularly common in Bengal and Bihar. It refers to the private land of the landlord, which would often be cultivated by peasants. Zerat was mainly responsible for a change in traditional forms of agricultural organization in some parts of India, replacing the ryot system. It produced a strain on the peasant economy, despite peasants being free to grow their own crops.

The East Bengal State Acquisition and Tenancy Act of 1950 was a law passed by the newly formed democratic Government of East Bengal in the Dominion of Pakistan. The bill was drafted on 31 March 1948 during the early years of Pakistan and passed on 16 May 1951. Before passage of the legislature, landed revenue laws of Bengal consisted of the Permanent Settlement Regulations of 1793 and the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1885.

The Zamindars of Bengal were zamindars of the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent. They governed an ancient system of land ownership.

Land reform refers to efforts to reform the ownership and regulation of land in India. Or, those lands which are redistributed by the government from landholders to landless people for agriculture or special purpose is known as Land Reform.

Zamindars of Natore were influential aristocratic Bengali Zamindars, who owned large estates in what is today Natore District in Bangladesh .

Pabna Peasant Uprising (1873–76) was a resistance movement by the peasants ("Ryots") against the lords of the lands in Bengal ("zamindars") in the Yusufshahi pargana in Pabna. It was led by Ishan Chandra Roy, Ishan Chandra Roy is known as "Bidrohi Raja"(বিদ্রোহী রাজা) or in English "Rebel King". It was supported by intellectuals such as R.C Dutt, Surendranath Banerjee, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, etc. It was overall a peaceful movement.

The Bengal Tenancy Act 1885 was an enactment of the Bengal government that defined the rights of zamindarslords and their tenants in response to a widespread peasant revolt. In "Pabna Revolts" or Pabna Agrarian Uprisings were actually mass meetings, strikes, and legal battles against exploitative zamindars that had started since 1870s.

The Mahalwari system was used in India to protect village-level-autonomy. It was introduced by Holt Mackenzie in 1822. The word "Mahalwari" is derived from the Hindi word Mahal, which means a community made from a group of villages. Mahalwari consisted of landlords or Lambardars assigned to represent villages or groups of villages. Along with the village communities, the landlords were jointly responsible for the payment of taxes. Revenue was determined on basis of the produce of Mahal. Individual responsibility was not assigned. The land included under this system consisted of all land in the villages, including forestland, pastures etc. This system was prevalent in parts of the Gangetic Valley, Uttar Pradesh, the North Western province, parts of Central India and Punjab.

Jotedars, also known as Hawladars, Ganitdars,Jwaddars, or Mandals, were landlords or, they can be well-to-do ryots, wealthy peasants who exercised control and influence comparable to that of a Zamindar but they were perceived as significantly below them in social strata in agrarian Bengal during Company rule in India. Jotedars owned relatively extensive tracts of land; their land tenure status stood in contrast to those of poor ryots and bargadars (sharecroppers), who were landless or land-poors. Many Hindu Jotedars in West Bengal were from the Bhadralok community, members of Hindu upper-castes of Bengal such as Kayastha, Brahmin, etc. Many Muslim Jotedars were from an Ashraf or Khandani family background, belonging the elite nobility of Bengali Muslims who descended from settled foreigners such as the Afghans, Mughals, Arabs, Persians, Turks and North Indian Immigrants. These socially high-standing Hindu and Muslim Jotedars who were not actually peasants had adopted the de jure status of ryot (peasant) solely for the financial benefit that the Bengal Tenancy Act of 1885 afforded to ryots, in addition due to consideration of the claim that Jotedars were got more freedoms and powers then Zamindars. Others belonged to the intermediate landowning peasant castes such as Sadgops, Aguris, Mahishyas, Rajbongshis, Shershahabadia and the rural, less educated Brahmins. By the 1920s a gentrified fraction of Jotedars emerged from the more prosperous peasants among the tribes such as Santhals and the Scheduled Castes such as the Bagdi and the NamasudrasJotedars were in actual control of village land and economy for a long period of time in history.

The Zamindars of Bihar were the autonomous and semi-autonomous rulers and administrators of the subah of Bihar during Mughal rule and later during British rule. They formed the landed aristocracy that lasted until Indian independence in 1947. The zamindars of Bihar were numerous and could be divided into small, medium and large depending on how much land they controlled. Within Bihar, the zamindars had both economic and military power. Each zamindari would have their own standing army which was typically composed of their own clansmen.

The zamindars of Mahipur were a Bengali aristocratic family of feudal landowners. The zamindari estate encompassed the Chakla of Qazirhat under the Cooch Behar State since the Mughal period. Although their aristocratic status was lost with the East Bengal State Acquisition and Tenancy Act of 1950, the Mahipur estate remains an important part of the history of Rangpur and belongs to one of the eighteen ancient zamindar families of Rangpur. The zamindari palace was lost as a result of flooding from the Teesta River, although the mosque, cemetery, polished reservoir and large draw-well can still be seen today.

References

- ↑ Ram, Bindeshwar (1997). Land and society in India: agrarian relations in colonial North Bihar. Orient Blackswan. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-81-250-0643-5 . Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ Cranenburgh, D. E. (1894). Unrepealed Acts of the Governor-General in Council, [India]. pp. 221–. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ "Ryot". TheFreeDictionary.com . Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ↑ "ryot". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021.

- ↑ Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Raiyat". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ Ram, p. 79

- ↑ Bengal (India). Land Records and Agriculture Dept (1896). Survey and settlement of the Dakhin Shahbazpur estates in the district of Backergunge, 1889-95. Bengal Secretariat Press. pp. 17–. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ Jha, Usha (2003). Land, labour, and power: agrarian crisis and the state in Bihar (1937–52). Aakar Books. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-81-87879-07-7 . Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ Buckland, C. E. (1901). Bengal under the lieutenant-governors: being a narrative of the principal events and public measures during their periods of office, from 1854–1898. S. K. Lahiri & Co. pp. 641–. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ Madan, G. R. (1990). India's developing villages. Allied Publishers. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-81-7023-281-0 . Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- 1 2 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ryot". Encyclopædia Britannica . Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 952.