Native American gaming comprises casinos, bingo halls, slots halls and other gambling operations on Indian reservations or other tribal lands in the United States. Because these areas have tribal sovereignty, states have limited ability to forbid gambling there, as codified by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988. As of 2011, there were 460 gambling operations run by 240 tribes, with a total annual revenue of $27 billion.

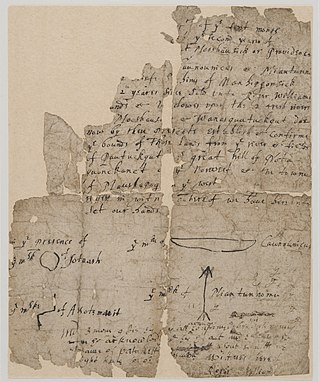

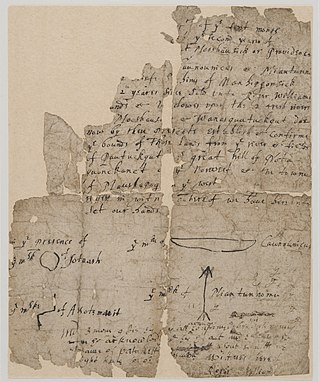

The Nonintercourse Act is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the United States Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set boundaries of American Indian reservations. The various acts were also intended to regulate commerce between White Americans and citizens of Indigenous nations. The most notable provisions of the act regulate the inalienability of aboriginal title in the United States, a continuing source of litigation for almost 200 years. The prohibition on purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government has its origins in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783.

United States v. Washington, 384 F. Supp. 312, aff'd, 520 F.2d 676, commonly known as the Boldt Decision, was a legal case in 1974 heard in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The case re-affirmed the rights of American Indian tribes in the state of Washington to co-manage and continue to harvest salmon and other fish under the terms of various treaties with the U.S. government. The tribes ceded their land to the United States but reserved the right to fish as they always had. This included their traditional locations off the designated reservations.

Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44 (1996), was a United States Supreme Court case which held that Article One of the U.S. Constitution did not give the United States Congress the power to abrogate the sovereign immunity of the states that is further protected under the Eleventh Amendment. Such abrogation is permitted where it is necessary to enforce the rights of citizens guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment as per Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer. The case also held that the doctrine of Ex parte Young, which allows state officials to be sued in their official capacity for prospective injunctive relief, was inapplicable under these circumstances, because any remedy was limited to the one that Congress had provided.

The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act is a 1988 United States federal law that establishes the jurisdictional framework that governs Indian gaming. There was no federal gaming structure before this act. The stated purposes of the act include providing a legislative basis for the operation/regulation of Indian gaming, protecting gaming as a means of generating revenue for the tribes, encouraging economic development of these tribes, and protecting the enterprises from negative influences. The law established the National Indian Gaming Commission and gave it a regulatory mandate. The law also delegated new authority to the U.S. Department of the Interior and created new federal offenses, giving the U.S. Department of Justice authority to prosecute them.

Tribal–state compacts are legal agreements between U.S. state government and Native American tribes primarily used for gambling, health care, child welfare, or other affairs. They are declared necessary for any Class III gaming on Indian reservations under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 (IGRA). They were designed to allow tribal and state governments to come to a "business" agreement. A compact can be thought of as "negotiated agreement between two political entities that resolves questions of overlapping jurisdictional responsibilities Compacts affect the delicate power balance between states, federal, and tribal governments. It is these forms that have been a major source of controversy surrounding Indian gaming. Thus, it is understandable that the IGRA provides very detailed instructions for how states and tribes can make compacts cooperatively and also details the instructions for how the federal government can regulate such agreements.

California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, 480 U.S. 202 (1987), was a United States Supreme Court case involving the development of Native American gaming. The Supreme Court's decision effectively overturned the existing laws restricting gaming/gambling on U.S. Indian reservations.

In United States law, the federal government as well as state and tribal governments generally enjoy sovereign immunity, also known as governmental immunity, from lawsuits. Local governments in most jurisdictions enjoy immunity from some forms of suit, particularly in tort. The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act provides foreign governments, including state-owned companies, with a related form of immunity—state immunity—that shields them from lawsuits except in relation to certain actions relating to commercial activity in the United States. The principle of sovereign immunity in US law was inherited from the English common law legal maxim rex non potest peccare, meaning "the king can do no wrong." In some situations, sovereign immunity may be waived by law.

South Dakota v. Bourland, 508 U.S. 679 (1993), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that Congress specifically abrogated treaty rights with the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe as to hunting and fishing rights on reservation lands that were acquired for a reservoir.

Bryan v. Itasca County, 426 U.S. 373 (1976), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that a state did not have the right to assess a tax on the property of a Native American (Indian) living on tribal land absent a specific Congressional grant of authority to do so.

The United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title. Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

The Connecticut Indian Land Claims Settlement was an Indian Land Claims Settlement passed by the United States Congress in 1983. The settlement act ended a lawsuit by the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe to recover 800 acres of their 1666 reservation in Ledyard, Connecticut. The state sold this property in 1855 without gaining ratification by the Senate. In a federal land claims suit, the Mashantucket Pequot charged that the sale was in violation of the Nonintercourse Act that regulates commerce between Native Americans and non-Indians.

Washington v. Confederated Bands and Tribes of the Yakima Indian Nation, 439 U.S. 463 (1979), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the State of Washington's imposition of partial jurisdiction over certain actions on an Indian reservation, when not requested by the tribe, was valid under Public Law 280.

New Mexico v. Mescalero Apache Tribe, 462 U.S. 324 (1983), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the application of New Mexico's laws to on-reservation hunting and fishing by nonmembers of the Tribe is preempted by the operation of federal law.

Oklahoma Tax Commission v. Sac & Fox Nation, 508 U.S. 114 (1993), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that absent explicit congressional direction to the contrary, it must be presumed that a State does not have jurisdiction to tax tribal members who live and work in Indian country, whether the particular territory consists of a formal or informal reservation, allotted lands, or dependent Indian communities.

Idaho v. United States, 533 U.S. 262 (2001), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that the United States, not the state of Idaho, held title to lands submerged under Lake Coeur d'Alene and the St. Joe River, and that the land was held in trust for the Coeur d'Alene Tribe as part of its reservation, and in recognition of the importance of traditional tribal uses of these areas for basic food and other needs.

United States v. John, 437 U.S. 634 (1978), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that lands designated as a reservation in Mississippi are "Indian country" as defined by statute, although the reservation was established nearly a century after Indian removal and related treaties. The court ruled that, under the Major Crimes Act, the State has no jurisdiction to try a Native American for crimes covered by that act that occurred on reservation land.

United States v. Antelope, 430 U.S. 641 (1977), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that American Indians convicted on reservation land were not deprived of the equal protection of the laws; (a) the federal criminal statutes are not based on impermissible racial classifications but on political membership in an Indian tribe or nation; and (b) the challenged statutes do not violate equal protection. Indians or non-Indians can be charged with first-degree murder committed in a federal enclave.

Ysleta del Sur Pueblo v. Texas, 596 U.S. ___ (2022), was a United States Supreme Court case dealing with whether the state of Texas could control and regulate gambling on Texan Native American reservations. In a 5–4 decision issued in June 2022, the Court ruled that the Restoration Act bans only gaming activities also banned by the state of Texas.

The Seminole Casino Coconut Creek is a casino located in Coconut Creek, Florida owned by the Seminole Tribe of Florida.