The Golden Madonna of Essen is a sculpture of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus. It is a wooden core covered with sheets of thin gold leaf. The piece is part of the treasury of Essen Cathedral, formerly the church of Essen Abbey, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, and is kept on display at the cathedral.

Essen Abbey was a community of secular canonesses for women of high nobility that formed the nucleus of modern-day Essen, Germany.

Saint Altfrid was a leading figure in Germany in the ninth century. A Benedictine monk, he became Bishop of Hildesheim, and founded Essen Abbey. He was also a close adviser to the East Frankish King Louis the German.

Essen Minster, since 1958 also Essen Cathedral is the seat of the Roman Catholic Bishop of Essen, the "Diocese of the Ruhr", founded in 1958. The church, dedicated to Saints Cosmas and Damian and the Blessed Virgin Mary, stands on the Burgplatz in the centre of the city of Essen, Germany.

Hellmut Diwald was a German historian and Professor of Medieval and Modern History at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg from 1965 to 1985.

The Sword of Saints Cosmas and Damian, also known as the Sword of Essen, is a ceremonial weapon in Essen Abbey. The sword itself dates to the mid 10th century, the gold decoration was added at the close of the 10th or the onset of the 11th century, while the silver mounts with the inscription were added 15th century.

Maria Kunigunde of Saxony was Princess-Abbess of Essen and Thorn. She was a titular Princess of Poland, Lithuania and Saxony of the Albertine branch of the House of Wettin. She was a member of the Order of the Starry Cross and a collegiate lady in the abbey at Münsterbilzen.

Princess Therese Natalie of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern was a German noblewoman. She was a member of the House of Welf and was princess-abbess of the Imperial Free secular Abbey in Gandersheim.

Beatrix von Holte was the Abbess of Essen Abbey from 1292 until her death.

The Essen Cathedral Treasury is one of the most significant collections of religious artworks in Germany. A great number of items of treasure are accessible to the public in the treasury chamber of Essen Minster. The cathedral chapter manages the treasury chamber, not as a museum as in some places, but as the place in which liturgical implements and objects are kept, which continued to be used to this day in the service of God, so far as their conservation requirements allow.

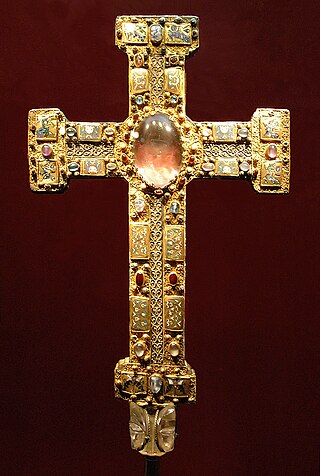

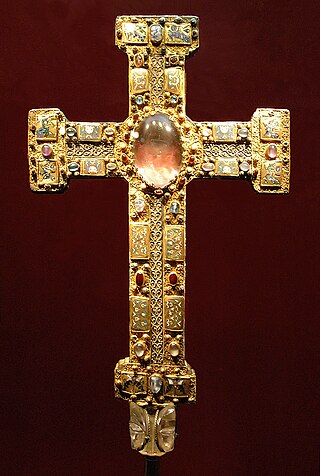

The Cross of Otto and Mathilde, Otto-Mathilda Cross, or First Cross of Mathilde is a medieval crux gemmata processional cross in the Essen Cathedral Treasury. It was created in the late tenth century and was used on high holidays until recently. It is named after the two persons who appear on the enamel plaque below Christ: Otto I, Duke of Swabia and Bavaria and his sister, Mathilde, the abbess of the Essen Abbey. They were grandchildren of the emperor Otto I and favourites of their uncle, Otto II. The cross is one of the items which demonstrate the very close relationship between the Liudolfing royal house and Essen Abbey. Mathilde became Abbess of Essen in 973 and her brother died in 982, so the cross is assumed to have been made between those dates, or a year or two later if it had a memorial function for Otto. Like other objects in Essen made under the patronage of Mathilde, the location of the goldsmith's workshop is uncertain, but as well as Essen itself, Cologne has often been suggested, and the enamel plaque may have been made separately in Trier.

Mathilde was Abbess of Essen Abbey from 973 to her death. She was one of the most important abbesses in the history of Essen. She was responsible for the abbey, for its buildings, its precious relics, liturgical vessels and manuscripts, its political contacts, and for commissioning translations and overseeing education. In the unreliable list of Essen Abbesses from 1672, she is listed as the second Abbess Mathilde and as a result, she is sometimes called "Mathilde II" to distinguish her from the earlier abbess of the same name, who is meant to have governed Essen Abbey from 907 to 910 but whose existence is disputed.

The Cross of Mathilde is an Ottonian processional cross in the crux gemmata style which has been in Essen in Germany since it was made in the 11th century. It is named after Abbess Mathilde who is depicted as the donor on a cloisonné enamel plaque on the cross's stem. It was made between about 1000, when Mathilde was abbess, and 1058, when Abbess Theophanu died; both were princesses of the Ottonian dynasty. It may have been completed in stages, and the corpus, the body of the crucified Christ, may be a still later replacement. The cross, which is also called the "second cross of Mathilde", forms part of a group along with the Cross of Otto and Mathilde or "first cross of Mathilde" from late in the preceding century, a third cross, sometimes called the Senkschmelz Cross, and the Cross of Theophanu from her period as abbess. All were made for Essen Abbey, now Essen Cathedral, and are kept in Essen Cathedral Treasury, where this cross is inventory number 4.

The Cross with large enamels, or Senkschmelz Cross, known in German as the Senkschmelzen-Kreuz or the Kreuz mit den großen Senkschmelzen, is a processional cross in the Essen Cathedral Treasury which was created under Mathilde, Abbess of Essen. The name refers to its principal decorations, five unusually large enamel plaques made using the senkschmelz technique, a form of cloisonné which looks forward to champlevé enamel, with a recessed area in enamel surrounded by a plain gold background, and distinguishes it from three other crosses of the crux gemmata type at Essen. The cross is considered one of the masterpieces of Ottonian goldsmithing.

The Cross of Theophanu is one of four Ottonian processional crosses in the Essen Cathedral Treasury and is among the most significant pieces of goldwork from that period. It was donated by Theophanu, Abbess of Essen, who reigned from 1039 to 1058.

The Essen Crown is an Ottonian golden crown in the Essen Cathedral Treasury. It was formerly claimed that it might have been the crown with which the three-year-old Otto III was crowned King of the Romans in 983, which is the source of its common name, the Childhood Crown of Otto III. However, this idea most probably derives from the wishful thinking of early twentieth century historians of Essen and it is now widely rejected. However it is certainly the oldest surviving lily crown in the world.

Georg Humann was a German art historian.

Elisabeth Countess of Nassau-Hadamar was an abbess in Essen. After some conflict, she was accepted as ruler of the city.

Jürgen Reulecke is a German historian and emeritus professor.