Background

The Uzbeks and Mughals' relations in the early 17th century was relatively peaceful, and the Janid ruler of Bukhara Imam Quli Khan had no intentions of jeopardizing the relationship, with Imam Quli even offering an alliance with the Mughals during their war with the Safavids. [9] Despite an attempt by Imam Quli's ambitious brother Nazr Muhammad to take Kabul in 1627, the Uzbeks still endeavored to maintain stable relations with the Mughals. [9] Muhammad also later sent an apology for the Kabul invasion in 1633 which Shah Jahan accepted. [9]

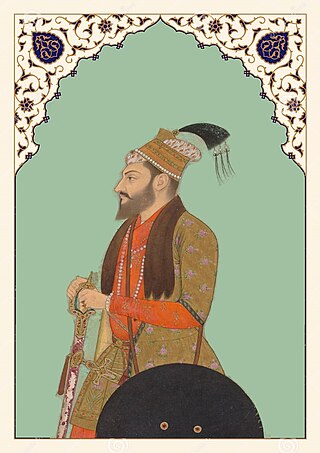

In the early 1640s, Imam Quli Khan contracted ophthalmia, resulting in blindness. Nazr Muhammad capitalized on this opportunity and took control, against the wishes of his brother. Nazr Muhammad died in Medina on pilgrimage in 1644. [9] Nazr Muhammad was widely unpopular in his territory, as a result of his strict administration and abundant taxation. [6] While in a campaign to conquer Khwarazm, the Atalıq of Muhammad's third son fell out with him and staged a revolt in Tashkent. [9] Muhammad sent his son Abd al-Aziz to put down the revolt, but he betrayed him, joining the rebels and usurping the throne. This left Nazr Muhammad with only the territories of Balkh and Badakhshan. [10] Shah Jahan was delighted with this outcome, as he was a known admirer of Transoxiana, part of Bukharan lands. Samarqand was one of the capitals of the Timurids, and the Indian Mughals at times cherished the dreams of gaining possession of the city which Babur had thrice won and lost. [11] This made Shah Jahan launch a military campaign. This was because the Mughal lineage found provenance in Transoxiana, with historian Abdul Hamid Lahori writing in the Padshahnama, a history of Shah Jahan's reign, that "The Emperor's heart had been set up the conquest of Balkh and Badakhshan, which were hereditary territories of his house, and were the keys to the acquisition of Samarqand, the home and capital of his great ancestor Timur Sahib Qiran Sani." Therefore, when he heard of the deposing of Nazr Muhammad, he understood it as an opportunity to regain Transoxiana. [9]

Campaign

Shah Jahan first sent a host of officers, including Asalat Khan and Persian general Ali Mardan Khan to scout the area. The first reconnoitre in June 1645 led to the Thanedaar of Ghorband, Khalil Beg, taking Kahmard as its defending force had left to defend Hisar from Abd al-Aziz. [9] However, he soon abandoned it and left for Zuhak, which resulted in Nazr Muhammad sending his generals Abdur Rahman and Tardi Ali Qatghan to retake the vulnerable fort. [6] Nonetheless, the imperialists pushed on towards Badakhshan. Beg deemed the roads to Badakhshan too narrow for the army and noted that they lacked provisions and would struggle in the imminent winter. Therefore, they returned to Kabul after looting a few district towns. [9] Later in October, a Rajput soldier, Raja Jagat Singh was sent on the second scouting mission to take Khost and build fortifications. He chose to build one between Andarab and Sarab which Nazr Muhammad's general Kafsh Qamaq attempted to take, but the 900 men army defended valiantly it until the Uzbeks retreated and reinforcements came, [9] with Jagat Singh returning to Kabul on November 4. [12] Meanwhile, Nazr Muhammad's rule was in disarray. His general and divan-begi Tardi Ali was exposed to be corrupt, which only made Muhammad more disliked with his people. [13] Abd al-Aziz detained Muhammad and only allowed him to administer Balkh. [9] Muhammad, fearing for his safety, wrote a letter to Shah Jahan calling for military help, which reached the emperor in late January 1646. [13]

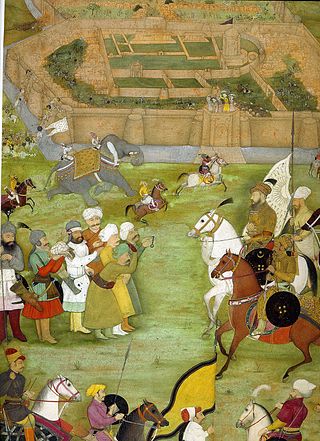

Upon receiving the letter, Shah Jahan began mobilizing troops for the campaign. Shah Jahan then went to Kabul to oversee the campaign, which was led by his youngest son Murad Bakhsh. The army consisted of 60,000 units, around 2,208 officers, and they set off in late May 1646. [9] The army split into two, one led by Murad and the other by Ali Mardan. [13] The two armies converged temporarily at Charikar to clear the snow, but soon split again. [14] Kilich Khan was instructed to capture Ghor and Kahmard. [9] Although he, along with Khalil Beg, seized Kahmard without much trouble, the inhabitants of Ghor fought very bravely and the Mughals spared the life of the governor of Ghor upon its capitulation. [13] Afterwards, Badakhshan succumbed to the Mughals. After Asalat Khan took Kunduz, Shah Jahan told Murad to tell Nazr Muhammad his territories in Balkh would be retained if he acted with submission. However, Muhammad thought cynically of the letter and fled to Persia, which enraged Murad; this led to his tracking Muhammad down in Persia but this came to no avail. [9] On July 2, Balkh was subdued without much force, and Muhammad's 70 million rupee treasury came under Mughal control, although they had only managed to retain 12 million for the local people had plundered most of it. [1] When hearing the news about Balkh, Shah Jahan was overjoyed and announced an 8 day holiday in celebration. He wrote to Persian shah Abbas II that he planned to take both Samarkand and Bukhara afterwards. [15]

Proceeding the relatively facile occupation of Balkh, Murad wrote home back to Shah Jahan in the middle of the festivities. Murad stated he was tired of the place, demanding to be recalled back to India. [13] Moreover, the disgruntled soldiers began to lose discipline and began plundering the city. [6] Shah Jahan indignantly replied that Murad would be viceroy of Transoxiana once Samarkand and Bukhara capitulated and Murad would be replaced and disgraced if he proceeded with leaving his post. This did not placate Murad however, and he returned to India, leaving his officers behind to govern the place. [9] Shah Jahan was incensed and relinquished Murad's title of mansab. [16] Shah Jahan then sent his reliable minister Saadullah Khan to govern the local towns and introduce standard currency in Balkh, which would be controlled by Bahadur Khan and Asalat Khan. [13] Saadullah Khan returned to Kabul on September 6. [9] A lack of a supreme leader led to the Mughal occupations in Balkh and Badakhshan being subject to frequent Uzbek attacks, engaging in many inconsequential conflicts with Uzbek tribes and raiders which only further incensed the soldiers. [6] Abd al-Aziz made it clear that he intended to capitalize on the Mughal struggles. [13]

In response, Shah Jahan redesignated his son Aurangzeb, then the governor of Gujarat, to lead the Central Asian Campaign and restore order with an army of around 25,000 men who departed from Kabul on April 1647. [16] Despite the comparative smallness size of his army in commensuration with Murad's, Aurangzeb made the Uzbeks flee at a valley called Derah-i-Garz and later defeated the Uzbeks near Balkh, then proceeding to the city with relative ease. They arrived at the city on May 25 and Aurangzeb left Rajput Madhu Singh Hada in command of the city. [6] However, upon hearing this information, Abd al-Aziz gathered a large force of around 120,000 men to thwart the Mughals, these troops were led by Qutluq Muhammad and Beg Ughli. [9] After three days at Balkh, Aurangzeb set off to confront the Uzbeks at Aqcha. They met on June 1, but Aurangzeb defeated them and prepared to retreat following the plunder of Beg Ughli's camp on June 5. [6] However, they were met with the full force of the Uzbek army on June 7, but managed to beat the disorganized Uzbeks and return to Balkh on the 11th. [6] Though, there were many difficulties for the Mughals at Balkh. The local people did not like the Mughals, and basic necessities were scarce. Shah Jahan knew that it would be impossible to maintain these provinces. Both sides wanted to make peace, with Abd al-Aziz quoted as saying "to fight with such a man [Aurangzeb] is to court one's ruin". [6] Shah Jahan wanted to concede Balkh to Nazr Muhammad on the basis he showed modesty. However, Muhammad accepted Balkh but did not show submission, on the basis of illness. In reality, he was a vain person and knew that they would accept anyway, given the impeding winter, which was proven to be true. The Indians were reluctant to face the winter of Bukhara. [15] Aurangzeb, desperate to leave Balkh, hastily agreed and left on October 3, 1647. The last of the Mughal army returned to Kabul on November 10, marking the end of the campaign. [6]