Related Research Articles

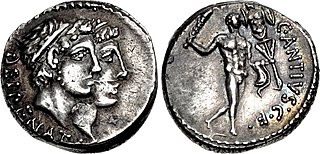

Hercules is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

Saturnalia is an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through to 23 December. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, and a public banquet, followed by private gift-giving, continual partying, and a carnival atmosphere that overturned Roman social norms: gambling was permitted, and masters provided table service for their slaves as it was seen as a time of liberty for both slaves and freedmen alike. A common custom was the election of a "King of the Saturnalia", who gave orders to people, which were followed and presided over the merrymaking. The gifts exchanged were usually gag gifts or small figurines made of wax or pottery known as sigillaria. The poet Catullus called it "the best of days".

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius, usually referred to as Macrobius, was a Roman provincial who lived during the early fifth century, during late antiquity, the period of time corresponding to the Later Roman Empire, and when Latin was as widespread as Greek among the elite. He is primarily known for his writings, which include the widely copied and read Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis about Somnium Scipionis, which was one of the most important sources for Neoplatonism in the Latin West during the Middle Ages; the Saturnalia, a compendium of ancient Roman religious and antiquarian lore; and De differentiis et societatibus graeci latinique verbi, which is now lost. He is the basis for the protagonist Manlius in Iain Pears' book The Dream of Scipio.

Festivals in ancient Rome were a very important part in Roman religious life during both the Republican and Imperial eras, and one of the primary features of the Roman calendar. Feriae were either public (publicae) or private (privatae). State holidays were celebrated by the Roman people and received public funding. Games (ludi), such as the Ludi Apollinares, were not technically feriae, but the days on which they were celebrated were dies festi, holidays in the modern sense of days off work. Although feriae were paid for by the state, ludi were often funded by wealthy individuals. Feriae privatae were holidays celebrated in honor of private individuals or by families. This article deals only with public holidays, including rites celebrated by the state priests of Rome at temples, as well as celebrations by neighborhoods, families, and friends held simultaneously throughout Rome.

Flora is a Roman goddess of flowers and of the season of spring – a symbol for nature and flowers. While she was otherwise a relatively minor figure in Roman mythology, being one among several fertility goddesses, her association with the spring gave her particular importance at the coming of springtime, as did her role as goddess of youth. She was one of the fifteen deities who had their own flamen, the Floralis, one of the flamines minores. Her Greek counterpart is Chloris.

Maia, in ancient Greek religion and mythology, is one of the Pleiades and the mother of Hermes, one of the major Greek gods, by Zeus, the king of Olympus.

The Temple of Hercules Victor or Hercules Olivarius ( is a Roman temple in Piazza Bocca della Verità in the area of the Forum Boarium near the Tiber in Rome. It is a tholos, a round temple of Greek 'peripteral' design completely surrounded by a colonnade. This layout caused it to be mistaken for a temple of Vesta until it was correctly identified by Napoleon's Prefect of Rome, Camille de Tournon.

The Great Altar of Unconquered Hercules stood in the Forum Boarium of ancient Rome. It was the earliest cult-centre of Hercules in Rome, predating the circular Temple of Hercules Victor. Roman tradition made the spot the site where Hercules slew Cacus and ascribed to Evander of Pallene its erection. Virgil's Aeneid tells of Evander attributing the original creation of the Ara Maxima to Potitius and the Pinarii.

The sellisternium or solisternium was a ritual banquet for goddesses in the Ancient Roman religion. It was based on a variant of the Greek theoxenias, and was considered an appropriately "greek" form of rite for some Roman goddesses thought to have been originally Greek, or with clearly Greek counterparts. In the traditional Roman lectisternium, the images of attending deities, usually male, reclined on couches along with their male hosts or guests. In the sellisternium, the attending goddesses sat on chairs or benches, usually in the company of exclusively female hosts and guests. A sellisternium for the Magna Mater was part of her ludi Megalenses; a representation of her temple on the Augustan Ara Pietatis probably shows her sellisternum, which includes Attis, her castrated consort. After Rome's great fire of 64 AD, a sellisternium was held to propitiate Juno. The secular games had a sellisternium for Juno and Diana, and according to Macrobius, a seated banquet of the gods and goddesses alike was part of Hercules' cult at the Ara Maxima.

Saturn was a god in ancient Roman religion, and a character in Roman mythology. He was described as a god of time, generation, dissolution, abundance, wealth, agriculture, periodic renewal and liberation. Saturn's mythological reign was depicted as a Golden Age of abundance and peace. After the Roman conquest of Greece, he was conflated with the Greek Titan Cronus. Saturn's consort was his sister Ops, with whom he fathered Jupiter, Neptune, Pluto, Juno, Ceres and Vesta.

The gens Antia was a minor plebeian family at ancient Rome. The Antii emerged at the end of the second century BC, and were of little importance during the Republic, but they continued into the third century, obtaining the consulship in AD 94 and 105.

The Mother of the Lares has been identified with any of several minor Roman deities. She appears twice in the records of the Arval Brethren as Mater Larum, elsewhere as Mania and Larunda. Ovid calls her Lara, Muta and Tacita.

The gens Potitia was an ancient patrician family at ancient Rome. None of its members ever attained any of the higher offices of the Roman state, and the gens is known primarily as a result of its long association with the rites of Hercules, and for a catastrophic plague that was said to have killed all of its members within a single month, at the end of the fourth century BC. However, a few Potitii of later times are known from literary sources and inscriptions.

The nundinae, sometimes anglicized to nundines, were the market days of the ancient Roman calendar, forming a kind of weekend including, for a certain period, rest from work for the ruling class (patricians).

Aphroditus or Aphroditos was a male Aphrodite originating from Amathus on the island of Cyprus and celebrated in Athens.

Cornelius Labeo was an ancient Roman theologian and antiquarian who wrote on such topics as the Roman calendar and the teachings of Etruscan religion (Etrusca disciplina). His works survive only in fragments and testimonia. He has been dated "plausibly but not provably" to the 3rd century AD. Labeo has been called "the most important Roman theologian" after Varro, whose work seems to have influenced him strongly. He is usually considered a Neoplatonist.

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Hercules was venerated as a divinized hero and incorporated into the legends of Rome's founding. The Romans adapted Greek myths and the iconography of Heracles into their own literature and art, but the hero developed distinctly Roman characteristics. Some Greek sources as early as the 6th and 5th century BC gave Heracles Roman connections during his famous labors.

Food and dining in the Roman Empire reflect both the variety of food-stuffs available through the expanded trade networks of the Roman Empire and the traditions of conviviality from ancient Rome's earliest times, inherited in part from the Greeks and Etruscans. In contrast to the Greek symposium, which was primarily a drinking party, the equivalent social institution of the Roman convivium was focused on food. Banqueting played a major role in Rome's communal religion. Maintaining the food supply to the city of Rome had become a major political issue in the late Republic, and continued to be one of the main ways the emperor expressed his relationship to the Roman people and established his role as a benefactor. Roman food vendors and farmers' markets sold meats, fish, cheeses, produce, olive oil and spices; and pubs, bars, inns and food stalls sold prepared food.

The Curia Calabra was a religious station or templum used for the ritual observation of the new moon in ancient Rome. Although its exact location is unclear, it was most likely a roofless enclosure in front of an augural hut (auguraculum), on the southwest flank of the Area Capitolina, the precinct of the Temple of Capitoline Jupiter. Servius identifies the Curia Calabra with a Casa Romuli on the Capitoline, but Macrobius implies that it was adjacent to the Casa.

The gens Pacuvia was a minor plebeian family at ancient Rome. Members of this gens are first mentioned during the second century BC, and from then down to the first century of the Empire Pacuvii are occasionally encountered in the historians. The first of the Pacuvii to achieve prominence at Rome, and certainly the most illustrious of the family, was the tragic poet Marcus Pacuvius.

References

- ↑ Robert A. Kaster, Macrobius: Saturnalia Books 1–2 (Loeb Classical Library, 2011), pp. 81 (note 110) and 110 (note 178).

- ↑ Caroline Vout, Power and Eroticism in Imperial Rome (Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 152.

- ↑ Claire Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome: The Retail Trade in the Late Republic and the Principate (Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 192.

- 1 2 Thomas, Emile (1899). Roman Life Under the Caesars. G. P. Putnam's sons. pp. 132–136. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ↑ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.11.1.

- ↑ Carlin A. Barton, The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster (Princeton University Press, 1993), p. 166.

- ↑ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.11.1.

- ↑ Macrobius Saturnalia 1.11.47

- ↑ Scholiast to Juvenal 6.154; Lawrence Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), p. 398; Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome, pp. 191–192.