Structural analyses

Broadly speaking, there are three competing analyses of the structure of small clauses. [14]

- the flat structure analysis treats the subject and predicate of the small clause as sister constituents

- the layered structure analysis treats the subject and predicate as a single "small clause" (SC) constituent

- the X-bar theory analysis treats the subject and predicate as a single constituent projected from the head of the small clause, which may be V, N, A, or P (with some analyses having additional functional structure) [15]

Flat structure

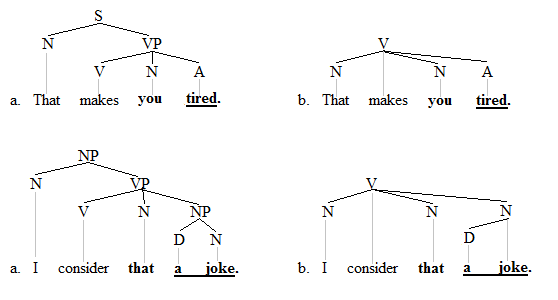

The flat structure organizes small clause material into two distinct sister constituents. [16]

The a-trees on the left are the phrase structure trees, and the b-trees on the right are the dependency trees. The key aspect of these structures is that the small clause material consists of two separate sister constituents.

The flat analysis is preferred by those working in dependency grammars and representational phrase structure grammars (e.g. Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar and Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar).

Layered structure

The layered structure organizes small clause material into one constituent. The phrase structure trees are again on the left, and the dependency trees on the right. To mark the small clause in the phrase structure trees, the node label SC is used.

The layered analysis is preferred by those working in the Government and Binding framework and its tradition, for examples see Chomsky, [17] Ouhalla, [11] Culicover, [16] : p47 Haegeman and Guéron. [13] : p108

X-Bar Theory structures

See X-Bar Theory for a general exploration of X-Bar Theory.

X-bar theory predicts that a head (X) will project into an intermediate constituent (X') and a maximal projection (XP). There were three common analyses of the internal structure of a small clause under X-Bar theory. [18] Here they are each presented as showing the NP AP small clause complement in the sentence (highlighted in bold), "I consider (NP)Mary (AP)smart":

Analysis 1: symmetric constituent

In this analysis, neither of the constituents determine the category, meaning that it is an exocentric construction. Some linguists believe that the label of this structure can be symmetrically determined by the constituents, [20] [21] and others believe that this structure lacks a label altogether. [22] In order to indicate a predicative relationship between the subject (in this case, the NP Mary), and the predicate (AP smart), some have suggested a system of co-indexation, where the subject must c-command any predicate associated with it. [23]

This analysis is not compatible with X-bar theory because X-bar theory does not allow for headless constituents, additionally this structure may not be an accurate representation of a small clause because it lacks an intermediate functional element that connects the subject with the predicate. Evidence of this element can be seen as an overt realization in a variety of languages such as Welsh, [24] Norwegian, [25] and English, as in the examples below [24] (with the overt predicative functional category highlighted in bold):

- I regard Fred as insane.

- I consider Fred as my best friend.

Some have taken this as evidence that this structure does not adequately portray the structure of a small clause, and that a better structure must include some intermediate projection that combines the subject and the predicate [1] which would assign a head to the constituent.

Analysis 2: projection of the predicate

In this analysis, the small clause can be identified as a projection of the predicate (in this example, the predicate would be the 'smart' in 'Mary smart'). In this view, the specifier of the structure (in this case, the NP 'Mary') is the subject of the head [26] (in this case, the A 'smart'). This analysis builds on Chomsky's [27] model of phrase structure and is proposed by Stowell [28] and Contreras. [29]

Analysis 3: projection of a functional category

The PrP [30] (predicate phrase) category (also analyzed as AgrP, [25] PredP, [31] and P [32] ), was proposed for a few reasons, some of which are outlined below:

- This structure helps to account for coordination where the categories of the items being coordinated must be the same. This accounts for the mystery of phrases such as (11) below, where a predicative adjective phrase (AP) is coordinated with a predicative noun phrase (NP), and this coordination of unlike categories is grammatical. The PrP analysis solves this problem by treating the constituents being coordinated as intermediate projection of the Pr head, namely Pr', as in (12). [32]

- Mayor Shinn considered Eulalie [APtalented ] and [NPa tyrant ]

- Mayor Shinn considered [PrPEulalie [Pr' (P) [APtalented ]] and [Pr' (P) [NPa tyrant ]]

- This structure answers the question of the category of the word as in small clause constructions such as I regard Fred as my best friend. This structure was an issue if as is analyzed as a preposition, as prepositions do not take adjective phrase complements. However, analyzing as as the overt realization of the Pr head is consistent with X-bar theory. [30]

Additionally, some have theorized that a combination of the three structures can illustrate why the subjects of verbal small clauses and adjectival small clauses seem to behave differently, as noted by Basilico: [33]

- The prisoner seems/appears to be intelligent.

- The prisoner seems/appears intelligent.

- The prisoner seems/appears to leave every day at noon.

- *The prisoner seems/appears leave every day at noon.

Here, examples (13) and (14) show that the subject of an adjectival small clause — with our without copular be — can raise to the matrix subject position. However, with a verbal clause, omission of infinitival to leads to ungrammatically, as shown by the contrast between the well-formed (15) and the ill-formed (16), where the asterisk (*) marks ungrammaticality. From this evidence, some linguists have theorized that the subjects of adjectival and verbal small clauses must differ in syntactic position. This conclusion is bolstered by the knowledge that verbal and adjectival small clauses differ in their predication forms. While adjectival small clauses involve categorical predication where the predicate ascribes a property to the subject, verbal small clauses involve thetic predications where an event that the subject is participating in is reported. [22] Basilico uses this to argue that a small clause should be analyzed as a Topic Phrase, which is projected from the predicate head (the Topic), with the subject introduced as the specifier of the Topic Phrase. [34] In this way, he argues that in an adjectival small clause, the predicate is formed for an individual topic, and in a verbal small clause the events form a predicate of events for a stage topic, which accounts for why verbal small clauses cannot be raised to the matrix subject position. [35]