Related Research Articles

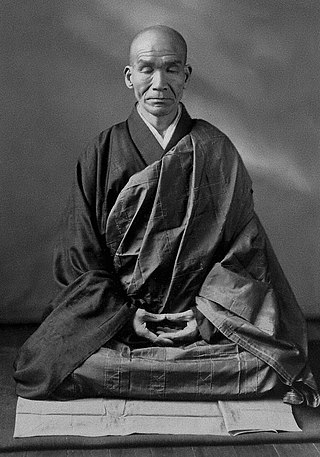

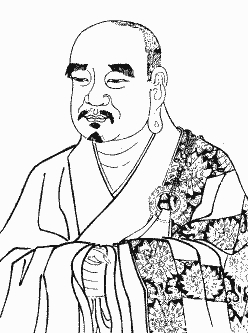

Dōgen Zenji, also known as Dōgen Kigen (道元希玄), Eihei Dōgen (永平道元), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (高祖承陽大師), or Busshō Dentō Kokushi (仏性伝東国師), was a Japanese Buddhist priest, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan.

Zazen is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

Kenshō (見性) is a Japanese term from the Zen tradition. Ken means "seeing", shō means "nature, essence". It is usually translated as "seeing one's (true) nature", that is, the Buddha-nature or nature of mind.

Eihei-ji (永平寺) is one of two main temples of the Sōtō school of Zen Buddhism, the largest single religious denomination in Japan. Eihei-ji is located about 15 km (9 mi) east of Fukui in Fukui Prefecture, Japan. In English, its name means "temple of eternal peace".

Shōbōgenzō is the title most commonly used to refer to the collection of works written in Japan by the 13th century Buddhist monk and founder of the Sōtō Zen school, Eihei Dōgen. Several other works exist with the same title, and it is sometimes called the Kana Shōbōgenzō in order to differentiate it from those. The term shōbōgenzō can also be used more generally as a synonym for Buddhism as viewed from the perspective of Mahayana Buddhism.

Shōhaku Okumura is a Japanese Sōtō Zen priest and the founder and abbot of the Sanshin Zen Community located in Bloomington, Indiana, where he and his family currently live. From 1997 until 2010, Okumura also served as director of the Sōtō Zen Buddhism International Center in San Francisco, California, which is an administrative office of the Sōtō school of Japan.

Bendōwa (辨道話), meaning Discourse on the Practice of the Way or Dialogue on the Way of Commitment, sometimes also translated as Negotiating the Way, On the Endeavor of the Way, or A Talk about Pursuing the Truth, is an influential essay written by Dōgen, the founder of Zen Buddhism's Sōtō school in Japan.

Gyobutsuji Zen Monastery is a small Sōtō Zen Buddhist monastery near Kingston in Madison County, Arkansas in the United States. It is located in the Boston Mountains of the Ozarks. The temple focuses primarily on the practice of zazen in the tradition of Kosho Uchiyama and Shohaku Okumura, the latter being the teacher of the founder, Shōryū Bradley. Study of the writings of Eihei Dōgen and the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha are also emphasized. The monastery holds a five-day sesshin every month except in January and August.

Keisei sanshoku, rendered in English as The Sounds of Valley Streams, the Forms of Mountains, is the 25th book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It was written in the spring of 1240 at Dōgen's monastery Kōshōhōrin-ji in Kyoto. The book appears in both the 75 and 60 fascicle versions of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered ninth in the later chronological 95 fascicle editions. The name keisei sanshoku is a quotation from the Song Dynasty Chinese poet Su Shi, wherein he experiences the sound of the valley stream as the preaching of the dharma and the mountain as the body of the Buddha. Dogen also discusses this verse of Su Shi in the later Shōbōgenzō books of Sansui Kyō and Mujō Seppō. About halfway through the essay, Dōgen switches from focusing on the title theme to a discussion of Buddhist ethics before ultimately concluding that one must practice ethical behavior in order to see the dharma in the natural world as Su Shi does.

Maka hannya haramitsu, the Japanese transliteration of Mahāprajñāpāramitā meaning The Perfection of Great Wisdom, is the second book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It is the second book in not only the original 60 and 75 fascicle versions of the text, but also the later 95 fascicle compilations. It was written in Kyoto in the summer of 1233, the first year that Dōgen began occupying the temple that what would soon become Kōshōhōrin-ji. As the title suggests, this chapter lays out Dōgen's interpretation of the Mahaprajñāpāramitāhṛdaya Sūtra, or Heart Sutra, so called because it is supposed to represent the heart of the 600 volumes of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra. The Heart Sutra focuses on the Buddhist concept of prajñā, or wisdom, which indicates not conventional wisdom, but rather wisdom regarding the emptiness of all phenomena. As Dōgen argues in this chapter, prajñā is identical to the practice of zazen, not a way of thinking.

Shinjin gakudō, translated into English as Learning the Truth with Body and Mind, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It was written in the fall of 1242 at Dōgen's first monastery Kōshōhōrin-ji in Kyoto. Shinjin gakudō appears in both the 75 and 60 fascicle versions of the Shōbōgenzō as the fourth book, and it is ordered 37th in the later chronological 95 fascicle Honzan editions. The book explains how truth can be obtained not with the mind alone, but rather with the body and mind together working through action. He further explains that action necessarily requires both the body and mind and that there is thus a oneness in action.

Gyōbutsu igi, known in English as Dignified Behavior of the Practice Buddha, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It was written in the winter of 1241 at Dōgen's monastery Kōshōhōrin-ji in Kyoto. The book appears as the sixth book in both the 75 and 60 fascicle versions of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered 23rd in the later chronological 95 fascicle Honzan editions. Dōgen discusses similar concepts in two of his formal Dharma Hall Discourses, namely number 119, which was written shortly after Gyōbutsu igi, and number 228, both of which are recorded in the Eihei Kōroku. The title is a quotation from the final chapter of Buddhabhadra's translation of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra where the phrase was used to simply describe the Buddha, "bearing himself as a Buddha." Dōgen substantially reimagines the meaning of the phrase in this fascicle.

Ikka myōju, known in English as One Bright Jewel or One Bright Pearl, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It was written in the summer of 1238 at Dōgen's monastery Kōshōhōrin-ji in Kyoto. The essay marked the beginning of a period of high output of Shōbōgenzō books that lasted until 1246. The book appears as the seventh book in both the 75 and 60 fascicle versions of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered fourth in the later chronological 95 fascicle Honzan editions. The essay is an extended commentary on the famous saying of the Tang dynasty monk Xuansha Shibei that "the ten-direction world is one bright jewel", which in turn references the Mani Jewel metaphors of earlier Buddhist scriptures. Dōgen also discusses the "one bright jewel" and related concepts from the Shōbōgenzō essay in two of his formal Dharma Hall Discourses, namely numbers 107 and 445, as well as his Kōan commentaries 23 and 41, all of which are recorded in the Eihei Kōroku.

Fukan zazengi, also known by its English translation Universal Recommendation for Zazen, is an essay describing and promoting the practice of zazen written by the 13th century Japanese Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. The date of its composition is unclear, and the text evolved significantly over the author's lifetime. It is written in Classical Chinese rather than the Classical Japanese Dōgen used to compose his famous Shōbōgenzō.

Sansui kyō, rendered in English as Mountains and Waters Sutra, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It is widely considered to be one of the most beautiful of all of the 95 books of the Shōbōgenzō according to Stanford University professor Carl Bielefeldt. The text was written in the fall of 1240 at Dōgen's monastery Kōshōhōrin-ji in Kyoto, and the manuscript from that time in Dōgen's own hand survives. This year saw a marked increase in the output of his essays for the Shōbōgenzō, including the closely related work Keisei sanshoku written a few months before and covering essentially the same theme, namely the mountains and rivers as equivalent to the body and speech of the Buddha. The book appears as the 29th in the 75 fascicle versions of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered 14th in the later chronological 95 fascicle Honzan edition. It was also included as the 14th book of the 28 fascicle "Eiheiji manuscript" Shōbōgenzō. Gudō Nishijima, a modern Zen priest, sums up the essay as follows: "Buddhism is basically a religion of belief in the universe, and nature is the universe showing its real form. So to look at nature is to look at the Buddhist truth itself. For this reason, Master Dōgen believed that nature is just Buddhist sutras."

Kobutsushin or Kobusshin, also known in various English translations such as The Mind of Eternal Buddhas or Old Buddha Mind, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. The book appears ninth in the 75 fascicle version of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered 44th in the later chronological 95 fascicle "Honzan edition". It was presented to his students in the fourth month of 1243 at Rokuharamitsu-ji, a temple in a neighborhood of eastern Kyoto populated primarily by military officials of the new Kamakura shogunate. This was the same location where he presented another book of the same collection called Zenki. Both were short works compared to others in the collection, and in both cases he was likely invited to present them at the behest of his main patron, Hatano Yoshishige, who lived nearby. Later in the same year, Dōgen suddenly abandoned his temple Kōshōhōrin-ji in Kyoto and began to establish Eihei-ji.

Zazen gi, also known in various English translations such as The Standard Method of Zazen or Principles of Zazen, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. The book appears tenth in the 75 fascicle version of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered 58th in the later chronological 95 fascicle "Honzan edition". It was presented to his students in the eleventh month of 1243 at Yoshimine shōja (吉峰精舍), a small temple where Dōgen and his sangha practiced briefly following their sudden move to Echizen Province from their previous temple Kōshōhōrin-ji earlier in the same year and before the establishment of Eihei-ji. Unlike other books of the Shōbōgenzō, it is not as much a commentary on classical Chinese Chan literature as it is a guide for the practice of zazen. The title comes from earlier Chinese texts of the same name and purpose, with a well known example found in the Chanyuan qinggui, from which Dōgen quotes extensively. His more famous Fukan zazengi, as well as Eihei shingi's Bendoho, also owe much to this Chinese text and are thus closely related to the Shōbōgenzō's Zazen gi.

Zazen shin, rendered in English as the Acupuncture Needle of Zazen, Lancet of Zazen, or Needle for Zazen, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It was written on the 19th of April in 1242 at Dōgen's monastery Kōshōhōrin-ji in Kyoto. The book appears as the 12th book in the 75 fascicle version of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered 27th in the later chronological 95 fascicle Honzan editions. The title Zazen shin refers to a poem of the same title written by Hongzhi Zhengjue. Hongzhi's poem is quoted verbatim in Dōgen's Zazen shin and also presented again in modified form later in the text.

The Japanese Buddhist word uji (有時), usually translated into English as Being-Time, is a key metaphysical idea of the Sōtō Zen founder Dōgen (1200-1253). His 1240 essay titled Uji, which is included as a fascicle in the Shōbōgenzō ("Treasury of the True Dharma Eye") collection, gives several explanations of uji, beginning with, "The so-called "sometimes" (uji) means: time (ji) itself already is none other than being(s) (u) are all none other than time (ji).". Scholars have interpreted uji "being-time" for over seven centuries. Early interpretations traditionally employed Buddhist terms and concepts, such as impermanence (Pali anicca, Japanese mujō無常). Modern interpretations of uji are more diverse, for example, authors like Steven Heine and Joan Stambaugh compare Dōgen's concepts of temporality with the existentialist Martin Heidegger's 1927 Being and Time.

Daichi Sokei (大智祖継) (1290–1366) was a Japanese Sōtō Zen monk famous for his Buddhist poetry who lived during the late Kamakura period and early Muromachi period. According to Steven Heine, a Buddhist studies professor, "Daichi is unique in being considered one of the great medieval Zen poets during an era when Rinzai monks, who were mainly located in Kyoto or Kamakura, clearly dominated the composition of verse."

References

- ↑ Nishijima, Gudo; Cross, Chodo (1994), Master Dogen's Shōbōgenzō, vol. 1, Dogen Sangha, pp. 65–73, ISBN 1-4196-3820-3

- ↑ Heine, Steven (2012), Dōgen: Textual and Historical Studies, Oxford University Press, p. 39, ISBN 978-0-19-975447-2

- ↑ Leighton, Taigen Dan; Okumura, Shohaku (2010), Dōgen's Extensive Record: A Translation of the Eihei Kōroku, Wisdom Publications, p. 588, ISBN 978-086171-670-8

- ↑ Tsunoda, Tairyu; Fujita, Issho, Sokushin Zebutsu: The Mind Itself is Buddha (PDF), Sōto School