Related Research Articles

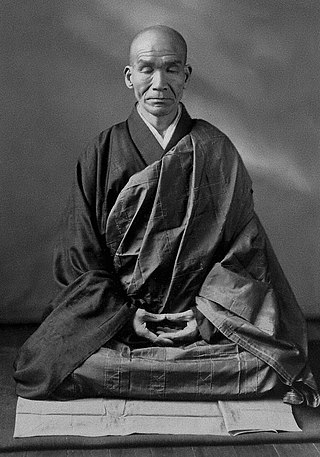

Dōgen Zenji, also known as Dōgen Kigen (道元希玄), Eihei Dōgen (永平道元), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (高祖承陽大師), or Busshō Dentō Kokushi (仏性伝東国師), was a Japanese Buddhist priest, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan.

Zazen is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

Philip Kapleau was an American teacher of Zen Buddhism in the Sanbo Kyodan tradition, which is rooted in Japanese Sōtō and incorporates Rinzai-school koan-study. He also strongly advocated for Buddhist vegetarianism.

Shōbōgenzō is the title most commonly used to refer to the collection of works written in Japan by the 13th century Buddhist monk and founder of the Sōtō Zen school, Eihei Dōgen. Several other works exist with the same title, and it is sometimes called the Kana Shōbōgenzō in order to differentiate it from those. The term shōbōgenzō can also be used more generally as a synonym for Buddhism as viewed from the perspective of Mahayana Buddhism.

Shōhaku Okumura is a Japanese Sōtō Zen priest and the founder and abbot of the Sanshin Zen Community located in Bloomington, Indiana, where he and his family currently live. From 1997 until 2010, Okumura also served as director of the Sōtō Zen Buddhism International Center in San Francisco, California, which is an administrative office of the Sōtō school of Japan.

Kosho Uchiyama was a Sōtō priest, origami master, and abbot of Antai-ji near Kyoto, Japan.

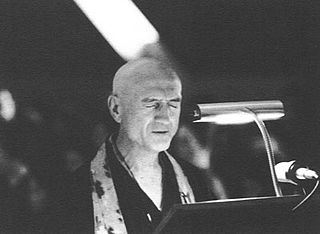

Hakuun Yasutani was a Sōtō priest and the founder of the Sanbo Kyodan, a lay Japanese Zen group. Through his students Philip Kapleau and Taizan Maezumi, Yasutani has been one of the principal forces in founding western (lay) Zen-practice.

Kazuaki Tanahashi is an accomplished Japanese calligrapher, Zen teacher, author and translator of Buddhist texts from Japanese and Chinese to English, most notably works by Dogen. He first met Shunryu Suzuki in 1964, and upon reading Suzuki's book Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind he stated, "I could see it's Shobogenzo in a very plain, simple language." He has helped notable Zen teachers author books on Zen Buddhism, such as John Daido Loori. A fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science—Tanahashi is also an environmentalist and peaceworker.

Taigen Dan Leighton is a Sōtō priest and teacher, academic, and author. He is an authorized lineage holder and Zen teacher in the tradition of Shunryū Suzuki and is the founder and Guiding Teacher of Ancient Dragon Zen Gate in Chicago, Illinois. Leighton is also an authorized teacher in the Japanese Sōtō School (kyōshi).

Bendōwa (辨道話), meaning Discourse on the Practice of the Way or Dialogue on the Way of Commitment, sometimes also translated as Negotiating the Way, On the Endeavor of the Way, or A Talk about Pursuing the Truth, is an influential essay written by Dōgen, the founder of Zen Buddhism's Sōtō school in Japan.

Tenzo Kyōkun (典座教訓), usually rendered in English as Instructions for the Cook, is an important essay written by Dōgen, the founder of Zen Buddhism's Sōtō school in Japan.

Book of Equanimity or Book of Serenity or Book of Composure is a book compiled by Wansong Xingxiu (1166–1246), and first published in 1224. The book comprises a collection of 100 koans written by the Chan Buddhist master Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091–1157), together with commentaries by Wansong. Wansong's compilation is the only surviving source for Hongzhi's koans.

Maka hannya haramitsu, the Japanese transliteration of Mahāprajñāpāramitā meaning The Perfection of Great Wisdom, is the second book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It is the second book in not only the original 60 and 75 fascicle versions of the text, but also the later 95 fascicle compilations. It was written in Kyoto in the summer of 1233, the first year that Dōgen began occupying the temple that what would soon become Kōshōhōrin-ji. As the title suggests, this chapter lays out Dōgen's interpretation of the Mahaprajñāpāramitāhṛdaya Sūtra, or Heart Sutra, so called because it is supposed to represent the heart of the 600 volumes of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra. The Heart Sutra focuses on the Buddhist concept of prajñā, or wisdom, which indicates not conventional wisdom, but rather wisdom regarding the emptiness of all phenomena. As Dōgen argues in this chapter, prajñā is identical to the practice of zazen, not a way of thinking.

Sokushin zebutsu, rendered in English as Mind is Itself Buddha, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It was written in the spring of 1239 at Dōgen's monastery Kōshōhōrin-ji in Kyoto. The book appears as the fifth book in both the 75 and 60 fascicle versions of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered sixth in the later chronological 95 fascicle Honzan editions. The title Sokushin zebutsu is an utterance attributed to the 8th century Song Dynasty Zen monk Mazu Daoyi in a well known kōan that appears most notably as Case 30 in The Gateless Barrier, although Dōgen would have known it from the earlier Transmission of the Lamp. In addition to this book of the Shōbōgenzō, Dōgen also discusses the phrase Sokushin zebutsu in several of his formal Dharma Hall Discourses, namely numbers 8, 75, 319, and 370, all of which are recorded in the Eihei Kōroku.

Gyōbutsu igi, known in English as Dignified Behavior of the Practice Buddha, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It was written in the winter of 1241 at Dōgen's monastery Kōshōhōrin-ji in Kyoto. The book appears as the sixth book in both the 75 and 60 fascicle versions of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered 23rd in the later chronological 95 fascicle Honzan editions. Dōgen discusses similar concepts in two of his formal Dharma Hall Discourses, namely number 119, which was written shortly after Gyōbutsu igi, and number 228, both of which are recorded in the Eihei Kōroku. The title is a quotation from the final chapter of Buddhabhadra's translation of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra where the phrase was used to simply describe the Buddha, "bearing himself as a Buddha." Dōgen substantially reimagines the meaning of the phrase in this fascicle.

Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki, sometimes known by its English translation The Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Record of Things Heard, is a collection of informal Dharma talks given by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen and recorded by his primary disciple Koun Ejō from 1236 to 1239. The text was likely further edited by other disciples after Ejō's death.

Eihei Kōroku, also known by its English translation Dōgen's Extensive Record, is a ten volume collection of works by the Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. The bulk of the text, accounting for volumes one through seven, are "Dharma hall discourses", which are highly formalized Dharma talks, given from 1236 to 1252. Volume eight consists of "informal meetings" that would have taken place in Dōgen's quarters with select groups of monks, as well as "Dharma words", which were letters containing practice instructions to specific students. Volume nine includes a collection of 90 traditional kōans with verse commentary by Dōgen, while volume 10 collects his Chinese poetry.

Ikka myōju, known in English as One Bright Jewel or One Bright Pearl, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It was written in the summer of 1238 at Dōgen's monastery Kōshōhōrin-ji in Kyoto. The essay marked the beginning of a period of high output of Shōbōgenzō books that lasted until 1246. The book appears as the seventh book in both the 75 and 60 fascicle versions of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered fourth in the later chronological 95 fascicle Honzan editions. The essay is an extended commentary on the famous saying of the Tang dynasty monk Xuansha Shibei that "the ten-direction world is one bright jewel", which in turn references the Mani Jewel metaphors of earlier Buddhist scriptures. Dōgen also discusses the "one bright jewel" and related concepts from the Shōbōgenzō essay in two of his formal Dharma Hall Discourses, namely numbers 107 and 445, as well as his Kōan commentaries 23 and 41, all of which are recorded in the Eihei Kōroku.

Daigo, also known in English translation as Great Realization, is a book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. The book appears tenth in the 75 fascicle version of the Shōbōgenzō, and it is ordered 26th in the later chronological 95 fascicle "Honzan edition". It was presented to his students in the first month of 1242 at Kōshōhōrin-ji, the first monastery established by Dōgen, located in Kyoto. According to Gudō Nishijima, a modern Zen priest, the "great realization" to which Dōgen refers is not an intellectual idea, but rather a "concrete realization of facts in reality" or "realization in real life". Shohaku Okumura, another modern-day Zen teacher, writes that Dōgen equates the term daigo with the network of interdependence in which all beings in the universe exist rather than something that we lack and need to obtain. Given this, Okumura writes that Dōgen is encouraging us to, "to realize great realization within this great realization, moment by moment; or perhaps it is better to say that great realization realizes great realization through our practice."

Shōryū Bradley is a Sōtō Zen priest and the founder and abbot of Gyobutsuji Zen Monastery located near Kingston, Arkansas.

References

- ↑ The fourth ideograph in this expression, as originally written by Dōgen, is not the same as that in the term kōan , which is written 公案. For discussion of the possible significance of this difference, see Okumura, Shohaku (2010). Realizing Genjokoan: The Key to Dogen's Shobogenzo. Wisdom Publications. p. 15 ff. ISBN 9780861716012.

- 1 2 Tanahashi, Kazuaki (1995). Moon in a Dewdrop . North Point Press. pp. 244–245. ISBN 9780865471863.

- 1 2 Weitsman, Mel; Wenger, Michael; Okumura, Shohaku (2012). Dogen's Genjo Koan: Three Commentaries. Counterpoint. p. 1. ISBN 9781582437439.

- 1 2 3 Thomas Cleary. "The Issue at Hand by Eihei Dogen". The Zen Site. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- 1 2 Taigen Dan Leighton. "The Practice of Genjokoan". Ancient Dragon Zen Gate. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Okumura, Shohaku (2010). Realizing Genjokoan: The Key to Dogen's Shobogenzo. Wisdom Publications. p. 13. ISBN 9780861716012.

- ↑ Yasutani, Hakuun (1996). Flowers Fall. A Commentary on Zen Master Dōgen's Genjōkōan. Boston: Shambala Publications. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-57062-674-6.

- ↑ Okumura, Shohaku (2010). Realizing Genjokoan: The Key to Dogen's Shobogenzo. Wisdom Publications. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9780861716012.

- ↑ Okumura, Shohaku (2010). Realizing Genjokoan: The Key to Dogen's Shobogenzo. Wisdom Publications. p. 21. ISBN 9780861716012.