Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and rendered in a specific time period by a country or countries. GDP is often used to measure the economic health of a country or region. Definitions of GDP are maintained by several national and international economic organizations, such as the OECD and the International Monetary Fund.

Income is the consumption and saving opportunity gained by an entity within a specified timeframe, which is generally expressed in monetary terms. Income is difficult to define conceptually and the definition may be different across fields. For example, a person's income in an economic sense may be different from their income as defined by law.

Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms. Microeconomics focuses on the study of individual markets, sectors, or industries as opposed to the economy as a whole, which is studied in macroeconomics.

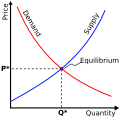

Neoclassical economics is an approach to economics in which the production, consumption, and valuation (pricing) of goods and services are observed as driven by the supply and demand model. According to this line of thought, the value of a good or service is determined through a hypothetical maximization of utility by income-constrained individuals and of profits by firms facing production costs and employing available information and factors of production. This approach has often been justified by appealing to rational choice theory.

A variety of measures of national income and output are used in economics to estimate total economic activity in a country or region, including gross domestic product (GDP), Gross national income (GNI), net national income (NNI), and adjusted national income. All are specially concerned with counting the total amount of goods and services produced within the economy and by various sectors. The boundary is usually defined by geography or citizenship, and it is also defined as the total income of the nation and also restrict the goods and services that are counted. For instance, some measures count only goods & services that are exchanged for money, excluding bartered goods, while other measures may attempt to include bartered goods by imputing monetary values to them.

Productivism or growthism is the belief that measurable productivity and growth are the purpose of human organization, and that "more production is necessarily good". Critiques of productivism center primarily on the limits to growth posed by a finite planet and extend into discussions of human procreation, the work ethic, and even alternative energy production.

Ecological economics, bioeconomics, ecolonomy, eco-economics, or ecol-econ is both a transdisciplinary and an interdisciplinary field of academic research addressing the interdependence and coevolution of human economies and natural ecosystems, both intertemporally and spatially. By treating the economy as a subsystem of Earth's larger ecosystem, and by emphasizing the preservation of natural capital, the field of ecological economics is differentiated from environmental economics, which is the mainstream economic analysis of the environment. One survey of German economists found that ecological and environmental economics are different schools of economic thought, with ecological economists emphasizing strong sustainability and rejecting the proposition that physical (human-made) capital can substitute for natural capital.

The Progressive utilization theory (PROUT) is a socioeconomic and political philosophy created by the Indian philosopher and spiritual leader Prabhat Ranjan Sarkar. He first conceived of PROUT in 1959. Its proponents (Proutists) claim that it exposes and overcomes the limitations of capitalism, communism and mixed economy. Since its genesis, PROUT has had an economically progressive approach, aiming to improve social development in the world. It is in line with Sarkar's Neohumanist values which aim to provide "proper care" to every being on the planet, including humans, animals and plants.

Gross National Happiness, sometimes called Gross Domestic Happiness (GDH), is a philosophy that guides the government of Bhutan. It includes an index which is used to measure the collective happiness and well-being of a population. Gross National Happiness Index is instituted as the goal of the government of Bhutan in the Constitution of Bhutan, enacted on 18 July 2008.

A steady-state economy is an economy made up of a constant stock of physical wealth (capital) and a constant population size. In effect, such an economy does not grow in the course of time. The term usually refers to the national economy of a particular country, but it is also applicable to the economic system of a city, a region, or the entire world. Early in the history of economic thought, classical economist Adam Smith of the 18th century developed the concept of a stationary state of an economy: Smith believed that any national economy in the world would sooner or later settle in a final state of stationarity.

Heterodox economics is a broad, relative term referring to schools of economic thought which are not commonly perceived as belonging to mainstream economics. There is no absolute definition of what constitutes heterodox economic thought, as it is defined in constrast to the most prominent, influential or popular schools of thought in a given time and place.

Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered is a collection of essays published in 1973 by German-born British economist E. F. Schumacher. The title "Small Is Beautiful" came from a principle espoused by Schumacher's teacher Leopold Kohr (1909–1994) advancing small, appropriate technologies, policies, and polities as a superior alternative to the mainstream ethos of "bigger is better".

The idea of want can be examined from many perspectives. In secular societies want might be considered similar to the emotion desire, which can be studied scientifically through the disciplines of psychology or sociology. Alternatively want can be studied in a non-secular, spiritual, moralistic or religious way, particularly by Buddhism but also Christianity, Islam and Judaism.

Tibor de Scitovsky, also known as Tibor Scitovsky, was a Hungarian born, American economist who was best known for his writing on the nature of people's happiness in relation to consumption. He was associate professor and professor of economics at Stanford University from 1946 through 1958 and Eberle Professor of Economics from 1970 until his retirement in 1976, when he became Professor Emeritus. In honor of his deep contributions to economic analysis, he was elected Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association, Fellow of the Royal Economic Society, member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy.

The Happy Planet Index (HPI) is an index of human well-being and environmental impact that was introduced by the New Economics Foundation in 2006. Each country's HPI value is a function of its average subjective life satisfaction, life expectancy at birth, and ecological footprint per capita. The exact function is a little more complex, but conceptually it approximates multiplying life satisfaction and life expectancy and dividing that by the ecological footprint. The index is weighted to give progressively higher scores to nations with lower ecological footprints.

Resource refers to all the materials available in our environment which are technologically accessible, economically feasible and culturally sustainable and help us to satisfy our needs and wants. Resources can broadly be classified according to their availability as renewable or national and international resources. An item may become a resource with technology. The benefits of resource utilization may include increased wealth, proper functioning of a system, or enhanced well. From a human perspective, a regular resource is anything to satisfy human needs and wants.

Sufficiency economy is the name of a Thai development approach attributed to the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej's "sufficiency economy philosophy" (SEP). It has been elaborated upon by Thai academics and agencies, promoted by the Government of Thailand, and applied by over 23,000 villages in Thailand that have SEP-based projects in operation.

In economics, scarcity "refers to the basic fact of life that there exists only a finite amount of human and nonhuman resources which the best technical knowledge is capable of using to produce only limited maximum amounts of each economic good." If the conditions of scarcity did not exist and an "infinite amount of every good could be produced or human wants fully satisfied ... there would be no economic goods, i.e. goods that are relatively scarce..." Scarcity is the limited availability of a commodity, which may be in demand in the market or by the commons. Scarcity also includes an individual's lack of resources to buy commodities. The opposite of scarcity is abundance. Scarcity plays a key role in economic theory, and it is essential for a "proper definition of economics itself".

"The best example is perhaps Walras' definition of social wealth, i.e., economic goods. 'By social wealth', says Walras, 'I mean all things, material or immaterial, that are scarce, that is to say, on the one hand, useful to us and, on the other hand, only available to us in limited quantity'."

In any technical subject, words commonly used in everyday life acquire very specific technical meanings, and confusion can arise when someone is uncertain of the intended meaning of a word. This article explains the differences in meaning between some technical terms used in economics and the corresponding terms in everyday usage.

Peasant economics is an area of economics in which a wide variety of economic approaches ranging from the neoclassical to the marxist are used to examine the political economy of the peasantry. The defining feature of the peasants are that they are typically seen to be only partly integrated into the market economy -— an economy which, in societies with a significant peasant population, is typically found to have many imperfect, incomplete or missing markets. Peasant economics treats peasants as something different from other farmers as they are not assumed to be simply small profit maximizing farmers; by contrast, peasant economics covers a wide range of different theories of peasant household behavior. These include various assumptions about the maximization of profits, risk aversion, drudgery aversion, and sharecropping. The assumptions, logic, and predictions of these theories are examined and the impact of subsistence is typically found to have important implications in terms of producers decisions about supply, consumption and price. Chayanov was an early proponent of the importance of understanding peasant behaviour arguing that peasants would work as hard as they needed in order to meet their subsistence needs, but had no incentive beyond those needs and therefore would slow and stop working once they were met. This principle, the consumption-labour-balance principle, implies that the peasant household will increase its work until it meets (balances) the needs (consumption) of the household. A possible implication of this view of peasant societies is that they will not develop without some external, added factor. Peasant economics has been seen as being an important area of study by some development economists, agricultural sociologists, and anthropologists.