Duḥkha (Sanskrit: दुःख; Pali: dukkha), "suffering", "pain," "unease," "unsatisfactory," is an important concept in Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism. Its meaning depends on the context, and may refer more specifically to the "unsatisfactoriness" or "unease" of transient existence, which we crave or grasp for when we are ignorant of this transientness. In Buddhism, dukkha is part of the first of the Four Noble Truths and one of the three marks of existence. The term also appears in scriptures of Hinduism, such as the Upanishads, in discussions of moksha.

In Buddhism, the Four Noble Truths are "the truths of the noble one ," a statement of how things really are when they are seen correctly. The four truths are

Nirvana is a concept in the Indian religions of Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism that refers to the extinguishing of the passions which is the ultimate state of salvational release and the liberation from duḥkha ('suffering') and saṃsāra, the cycle of birth and rebirth.

The Noble Eightfold Path or Eight Right Paths is an early summary of the path of Buddhist practices leading to liberation from samsara, the painful cycle of rebirth, in the form of nirvana.

Saṃsāra is a Sanskrit word that means "wandering" as well as "world," wherein the term connotes "cyclic change" or, less formally, "running around in circles." Saṃsāra is referred to with terms or phrases such as transmigration/reincarnation, karmic cycle, or Punarjanman, and "cycle of aimless drifting, wandering or mundane existence". When related to the theory of karma it is the cycle of death and rebirth.

In Buddhism, the term anattā or anātman is the doctrine of "no-self" – that no unchanging, permanent self or essence can be found in any phenomenon. While often interpreted as a doctrine denying the existence of a self, anatman is more accurately described as a strategy to attain non-attachment by recognizing everything as impermanent, while staying silent on the ultimate existence of an unchanging essence. In contrast, dominant schools of Hinduism assert the existence of Ātman as pure awareness or witness-consciousness, "reify[ing] consciousness as an eternal self."

In Buddhism, the three marks of existence are three characteristics of all existence and beings, namely anicca (impermanence), dukkha, and anattā. The concept of humans being subject to delusion about the three marks, this delusion resulting in suffering, and removal of that delusion resulting in the end of dukkha, is a central theme in the Buddhist Four Noble Truths, the last of which leads to the Noble Eightfold Path.

Rebirth in Buddhism refers to the teaching that the actions of a sentient being lead to a new existence after death, in an endless cycle called saṃsāra. This cycle is considered to be dukkha, unsatisfactory and painful. The cycle stops only if Nirvana (liberation) is achieved by insight and the extinguishing of craving. Rebirth is one of the foundational doctrines of Buddhism, along with karma and Nirvana. Rebirth was a key teaching of early Buddhism along with the doctrine of karma. In Early Buddhist Sources, the Buddha claims to have knowledge of his many past lives. Rebirth and other concepts of the afterlife have been interpreted in different ways by different Buddhist traditions.

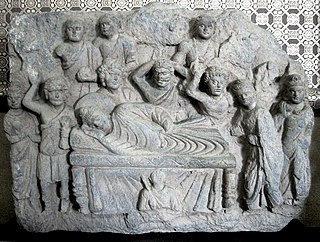

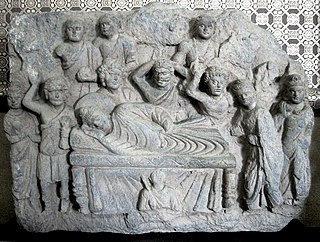

In Buddhism, parinirvana describes the state entered after death by someone who has attained nirvana during their lifetime. It implies a release from Saṃsāra, karma and rebirth as well as the dissolution of the skandhas.

Taṇhā is an important concept in Buddhism, referring to "thirst, desire, longing, greed", either physical or mental. It is typically translated as craving, and is of three types: kāma-taṇhā, bhava-taṇhā, and vibhava-taṇhā.

Buddhism, also known as Buddha Dharma, is an Indian religion and philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or 5th century BCE. It is the world's fourth-largest religion, with over 520 million followers, known as Buddhists, who comprise seven percent of the global population. It arose in the eastern Gangetic plain as a śramaṇa movement in the 5th century BCE, and gradually spread throughout much of Asia. Buddhism has subsequently played a major role in Asian culture and spirituality, eventually spreading to the West in the 20th century.

Avidyā in Buddhist literature is commonly translated as "ignorance". The concept refers to ignorance or misconceptions about the nature of metaphysical reality, in particular about the impermanence and anatta doctrines about reality. It is the root cause of Dukkha, and asserted as the first link, in Buddhist phenomenology, of a process that leads to repeated birth.

Karma is a Sanskrit term that literally means "action" or "doing". In the Buddhist tradition, karma refers to action driven by intention (cetanā) which leads to future consequences. Those intentions are considered to be the determining factor in the kind of rebirth in samsara, the cycle of rebirth.

Brahmā is a leading God (deva) and heavenly king in Buddhism. He is considered as a protector of teachings (dharmapala), and he is never depicted in early Buddhist texts as a creator god. In Buddhist tradition, it was the deity Brahma Sahampati who appeared before the Buddha and invited him to teach, once the Buddha attained enlightenment.

Pre-sectarian Buddhism, also called early Buddhism, the earliest Buddhism, original Buddhism, and primitive Buddhism, is Buddhism as theorized to have existed before the various Early Buddhist schools developed, around 250 BCE.

Nirvana is the extinguishing of the passions, the "blowing out" or "quenching" of the activity of the grasping mind and its related unease. Nirvana is the goal of many Buddhist paths, and leads to the soteriological release from dukkha ('suffering') and rebirths in saṃsāra. Nirvana is part of the Third Truth on "cessation of dukkha" in the Four Noble Truths, and the "summum bonum of Buddhism and goal of the Eightfold Path."

The three poisons in the Mahayana tradition or the three unwholesome roots, in the Theravada tradition are a Buddhist term that refers to the three root kleshas that lead to all negative states. These three states are delusion, also known as ignorance; greed or sensual attachment; and hatred or aversion. These three poisons are considered to be three afflictions or character flaws that are innate in beings and the root of craving, and so causing suffering and rebirth.

Karma is an important topic in Buddhist thought. The concept may have been of minor importance in early Buddhism, and various interpretations have evolved throughout time. A main problem in Buddhist philosophy is how karma and rebirth are possible, when there is no self to be reborn, and how the traces or "seeds" of karma are stored throughout time in consciousness.

Impermanence, called anicca (Pāli) or anitya (Sanskrit), appears extensively in the Pali Canon as one of the essential doctrines of Buddhism. The doctrine asserts that all of conditioned existence, without exception, is "transient, evanescent, inconstant".

The Six Paths in Buddhist cosmology are the six worlds where sentient beings are reincarnated based on their karma, which is linked to their actions in previous lives. These paths are depicted in the Bhavacakra. The six paths are:

- the world of gods or celestial beings (deva) ;

- the world of warlike demigods (asura) ;

- the world of human beings (manushya) ;

- the world of animals (tiryagyoni) ;

- the world of hungry ghosts (preta) ;

- the world of Hell (naraka).