Related Research Articles

Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily. It is important for reasoning and the guidance of decision-making and behavior. Working memory is often used synonymously with short-term memory, but some theorists consider the two forms of memory distinct, assuming that working memory allows for the manipulation of stored information, whereas short-term memory only refers to the short-term storage of information. Working memory is a theoretical concept central to cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience.

Human intelligence is the intellectual capability of humans, which is marked by complex cognitive feats and high levels of motivation and self-awareness. Using their intelligence, humans are able to learn, form concepts, understand, and apply logic and reason. Human intelligence is also thought to encompass our capacities to recognize patterns, plan, innovate, solve problems, make decisions, retain information, and use language to communicate.

In the philosophy of mind, neuroscience, and cognitive science, a mental image is an experience that, on most occasions, significantly resembles the experience of "perceiving" some object, event, or scene but occurs when the relevant object, event, or scene is not actually present to the senses. There are sometimes episodes, particularly on falling asleep and waking up, when the mental imagery may be dynamic, phantasmagoric, and involuntary in character, repeatedly presenting identifiable objects or actions, spilling over from waking events, or defying perception, presenting a kaleidoscopic field, in which no distinct object can be discerned. Mental imagery can sometimes produce the same effects as would be produced by the behavior or experience imagined.

In cognitive psychology and neuroscience, spatial memory is a form of memory responsible for the recording and recovery of information needed to plan a course to a location and to recall the location of an object or the occurrence of an event. Spatial memory is necessary for orientation in space. Spatial memory can also be divided into egocentric and allocentric spatial memory. A person's spatial memory is required to navigate around a familiar city. A rat's spatial memory is needed to learn the location of food at the end of a maze. In both humans and animals, spatial memories are summarized as a cognitive map.

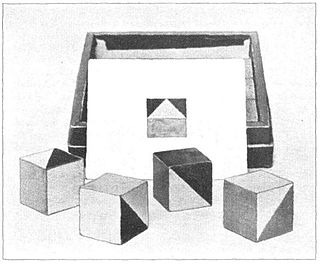

A block design test is a subtest on many IQ test batteries used as part of assessment of human intelligence. It is thought to tap spatial visualization ability and motor skill. The test-taker uses hand movements to rearrange blocks that have various color patterns on different sides to match a pattern. The items in a block design test can be scored both by accuracy in matching the pattern and by speed in completing each item.

Visual memory describes the relationship between perceptual processing and the encoding, storage and retrieval of the resulting neural representations. Visual memory occurs over a broad time range spanning from eye movements to years in order to visually navigate to a previously visited location. Visual memory is a form of memory which preserves some characteristics of our senses pertaining to visual experience. We are able to place in memory visual information which resembles objects, places, animals or people in a mental image. The experience of visual memory is also referred to as the mind's eye through which we can retrieve from our memory a mental image of original objects, places, animals or people. Visual memory is one of several cognitive systems, which are all interconnected parts that combine to form the human memory. Types of palinopsia, the persistence or recurrence of a visual image after the stimulus has been removed, is a dysfunction of visual memory.

Mental rotation is the ability to rotate mental representations of two-dimensional and three-dimensional objects as it is related to the visual representation of such rotation within the human mind. There is a relationship between areas of the brain associated with perception and mental rotation. There could also be a relationship between the cognitive rate of spatial processing, general intelligence and mental rotation.

Numerical cognition is a subdiscipline of cognitive science that studies the cognitive, developmental and neural bases of numbers and mathematics. As with many cognitive science endeavors, this is a highly interdisciplinary topic, and includes researchers in cognitive psychology, developmental psychology, neuroscience and cognitive linguistics. This discipline, although it may interact with questions in the philosophy of mathematics, is primarily concerned with empirical questions.

The concept of motor cognition grasps the notion that cognition is embodied in action, and that the motor system participates in what is usually considered as mental processing, including those involved in social interaction. The fundamental unit of the motor cognition paradigm is action, defined as the movements produced to satisfy an intention towards a specific motor goal, or in reaction to a meaningful event in the physical and social environments. Motor cognition takes into account the preparation and production of actions, as well as the processes involved in recognizing, predicting, mimicking, and understanding the behavior of other people. This paradigm has received a great deal of attention and empirical support in recent years from a variety of research domains including embodied cognition, developmental psychology, cognitive neuroscience, and social psychology.

In psychology and neuroscience, executive dysfunction, or executive function deficit, is a disruption to the efficacy of the executive functions, which is a group of cognitive processes that regulate, control, and manage other cognitive processes. Executive dysfunction can refer to both neurocognitive deficits and behavioural symptoms. It is implicated in numerous psychopathologies and mental disorders, as well as short-term and long-term changes in non-clinical executive control.

It has been estimated that over 20% of adults suffer from some form of sleep deprivation. Insomnia and sleep deprivation are common symptoms of depression, and can be an indication of other mental disorders. The consequences of not getting enough sleep could have dire results; not only to the health, cognition, energy level and the mood of the individual, but also to those around them as sleep deprivation increases the risk of human-error related accidents, especially with vigilance-based tasks involving technology.

Spatial cognition is the acquisition, organization, utilization, and revision of knowledge about spatial environments. It is most about how animals including humans behave within space and the knowledge they built around it, rather than space itself. These capabilities enable individuals to manage basic and high-level cognitive tasks in everyday life. Numerous disciplines work together to understand spatial cognition in different species, especially in humans. Thereby, spatial cognition studies also have helped to link cognitive psychology and neuroscience. Scientists in both fields work together to figure out what role spatial cognition plays in the brain as well as to determine the surrounding neurobiological infrastructure.

Attentional control, colloquially referred to as concentration, refers to an individual's capacity to choose what they pay attention to and what they ignore. It is also known as endogenous attention or executive attention. In lay terms, attentional control can be described as an individual's ability to concentrate. Primarily mediated by the frontal areas of the brain including the anterior cingulate cortex, attentional control is thought to be closely related to other executive functions such as working memory.

The neuroscience of sex differences is the study of characteristics that separate the male and female brains. Psychological sex differences are thought by some to reflect the interaction of genes, hormones, and social learning on brain development throughout the lifespan.

Visual spatial attention is a form of visual attention that involves directing attention to a location in space. Similar to its temporal counterpart visual temporal attention, these attention modules have been widely implemented in video analytics in computer vision to provide enhanced performance and human interpretable explanation of deep learning models.

Sex differences in human intelligence have long been a topic of debate among researchers and scholars. It is now recognized that there are no significant sex differences in general intelligence, though particular subtypes of intelligence vary somewhat between sexes.

Sex differences in cognition are widely studied in the current scientific literature. Biological and genetic differences in combination with environment and culture have resulted in the cognitive differences among males and females. Among biological factors, hormones such as testosterone and estrogen may play some role mediating these differences. Among differences of diverse mental and cognitive abilities, the largest or most well known are those relating to spatial abilities, social cognition and verbal skills and abilities.

Spatial ability or visuo-spatial ability is the capacity to understand, reason, and remember the visual and spatial relations among objects or space.

In psychology and neuroscience, multiple object tracking (MOT) refers to the ability of humans and other animals to simultaneously monitor multiple objects as they move. It is also the term for certain laboratory techniques used to study this ability.

Spatial anxiety is a sense of anxiety an individual experiences while processing environmental information contained in one's geographical space, with the purpose of navigation and orientation through that space. Spatial anxiety is also linked to the feeling of stress regarding the anticipation of a spatial-content related performance task. Particular cases of spatial anxiety can result in a more severe form of distress, as in agoraphobia.

References

Inline citations

- ↑ Mitchell, J.; Kent, L. (2003). "Apparency of contingencies in single panel and pull-down menus". International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 49 (1): 59–78. doi:10.1006/ijhc.1998.0200.

- ↑ Vicente, K. J.; Hayes, B. C.; Williges, R. C. (June 1987). "Assaying and isolating individual differences in searching a hierarchical file system". Human Factors . 29 (3): 349–359. doi:10.1177/001872088702900308. ISSN 0018-7208. PMID 3623569. S2CID 5395157.

- ↑ Robert, Michèle; Chevrier, Eliane (October 2003). "Does men's advantage in mental rotation persist when real three-dimensional objects are either felt or seen?". Memory & Cognition . 31 (7): 1136–1145. doi: 10.3758/BF03196134 . ISSN 0090-502X. PMID 14704028.

- ↑ Feng, Jing; Spence, Ian; Pratt, Jay (2016-05-06). "Playing an Action Video Game Reduces Gender Differences in Spatial Cognition". Psychological Science . 18 (10): 850–855. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.392.9474 . doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01990.x. PMID 17894600. S2CID 5885796.

- ↑ Witkin, H. A.; Lewis, H. B.; Hertzman, M.; Machover, K.; Meissner, P. B.; Wapner, S. (1954). Personality through perception: An experimental and clinical study. New York: Harper. OCLC 2660853.

- ↑ Barnett-Cowan, M.; Dyde, R. T.; Thompson, C.; Harris, L. R. (2010). "Multisensory determinants of orientation perception: task-specific sex differences". European Journal of Neuroscience . 31 (10): 1899–1907. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07199.x . ISSN 1460-9568. PMID 20584195. S2CID 1153800.

- ↑ Koscik, Tim; Moser, David J.; Andreasen, Nancy C.; Nopoulos, Peg (2008). "Sex Differences in Parietal Lobe Morphology: Relationship to Mental Rotation Performance". Brain and Cognition. 69 (3): 451–459. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2008.09.004. PMC 2680714 . PMID 18980790.

- ↑ McGlone, Matthew S.; Aronson, Joshua (2006). "Stereotype threat, identity salience, and spatial reasoning". Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology . 27 (5): 486–493. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2006.06.003.

General references

- Alonso, D. L. (1998). "The effects of individual differences in spatial visualization ability on dual-task performance" . Retrieved 2006-05-14.

- Downing, R. E.; Moore, J. L.; Brown, S. W. (2005). "The effects and interaction of spatial visualization and domain expertise on information seeking". Computers in Human Behavior . 21 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2004.03.040.

- Ozer, D. J. (1987). "Personality, intelligence, and spatial visualization: Correlates of mental rotations test performance". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . 53 (1): 129–134. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.1.129. PMID 3612485.

- Salthouse, T. A.; Babcock, R. L.; Skovronek, E.; Mitchell, D. R. D.; Palmon, R. (1990). "Age and experience effects in spatial visualization". Developmental Psychology . 26 (1): 128–136. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.26.1.128.

- Salthouse, T. A.; Mitchell, D. R. D (1990). "Effects of age and naturally occurring experience on spatial visualization performance". Developmental Psychology . 26 (5): 845–854. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.26.5.845.

- Zhang, H.; Salvendy, G. (2001). "The implications of visualization ability and structure preview design for web information search tasks". International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction . 13 (1): 75–95. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.150.8722 . doi:10.1207/S15327590IJHC1301_5. S2CID 1576458.