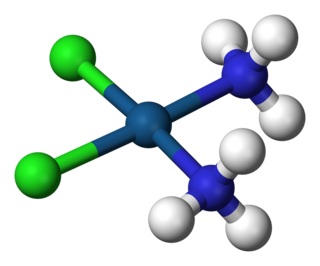

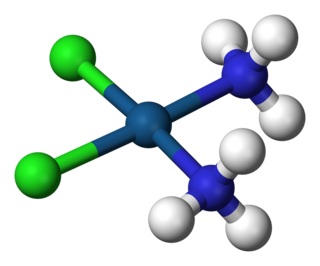

A coordination complex is a chemical compound consisting of a central atom or ion, which is usually metallic and is called the coordination centre, and a surrounding array of bound molecules or ions, that are in turn known as ligands or complexing agents. Many metal-containing compounds, especially those that include transition metals, are coordination complexes.

Inorganic chemistry deals with synthesis and behavior of inorganic and organometallic compounds. This field covers chemical compounds that are not carbon-based, which are the subjects of organic chemistry. The distinction between the two disciplines is far from absolute, as there is much overlap in the subdiscipline of organometallic chemistry. It has applications in every aspect of the chemical industry, including catalysis, materials science, pigments, surfactants, coatings, medications, fuels, and agriculture.

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule with a functional group that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's electron pairs, often through Lewis bases. The nature of metal–ligand bonding can range from covalent to ionic. Furthermore, the metal–ligand bond order can range from one to three. Ligands are viewed as Lewis bases, although rare cases are known to involve Lewis acidic "ligands".

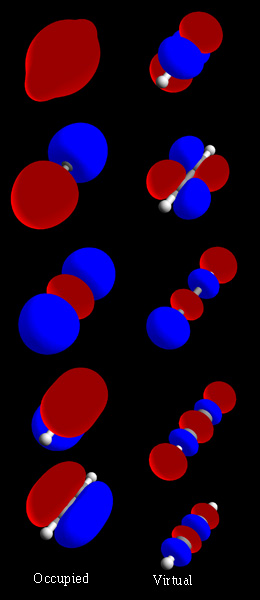

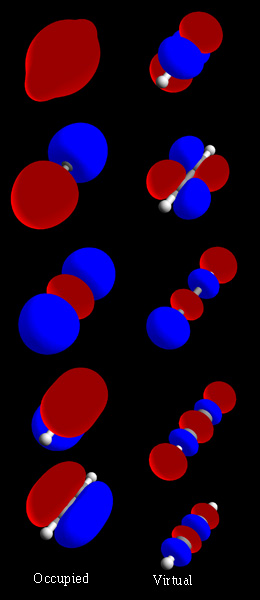

In chemistry, a molecular orbital is a mathematical function describing the location and wave-like behavior of an electron in a molecule. This function can be used to calculate chemical and physical properties such as the probability of finding an electron in any specific region. The terms atomic orbital and molecular orbital were introduced by Robert S. Mulliken in 1932 to mean one-electron orbital wave functions. At an elementary level, they are used to describe the region of space in which a function has a significant amplitude.

In chemistry, a transition metal is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table, though the elements of group 12 are sometimes excluded. The lanthanide and actinide elements are called inner transition metals and are sometimes considered to be transition metals as well.

Valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory is a model used in chemistry to predict the geometry of individual molecules from the number of electron pairs surrounding their central atoms. It is also named the Gillespie-Nyholm theory after its two main developers, Ronald Gillespie and Ronald Nyholm.

In molecular physics, crystal field theory (CFT) describes the breaking of degeneracies of electron orbital states, usually d or f orbitals, due to a static electric field produced by a surrounding charge distribution. This theory has been used to describe various spectroscopies of transition metal coordination complexes, in particular optical spectra (colors). CFT successfully accounts for some magnetic properties, colors, hydration enthalpies, and spinel structures of transition metal complexes, but it does not attempt to describe bonding. CFT was developed by physicists Hans Bethe and John Hasbrouck van Vleck in the 1930s. CFT was subsequently combined with molecular orbital theory to form the more realistic and complex ligand field theory (LFT), which delivers insight into the process of chemical bonding in transition metal complexes. CFT can be complicated further by breaking assumptions made of relative metal and ligand orbital energies, requiring the use of inverted ligand field theory (ILFT) to better describe bonding.

Ligand field theory (LFT) describes the bonding, orbital arrangement, and other characteristics of coordination complexes. It represents an application of molecular orbital theory to transition metal complexes. A transition metal ion has nine valence atomic orbitals - consisting of five nd, one (n+1)s, and three (n+1)p orbitals. These orbitals have the appropriate energy to form bonding interactions with ligands. The LFT analysis is highly dependent on the geometry of the complex, but most explanations begin by describing octahedral complexes, where six ligands coordinate with the metal. Other complexes can be described with reference to crystal field theory. Inverted ligand field theory (ILFT) elaborates on LFT by breaking assumptions made about relative metal and ligand orbital energies.

In organometallic chemistry, the isolobal principle is a strategy used to relate the structure of organic and inorganic molecular fragments in order to predict bonding properties of organometallic compounds. Roald Hoffmann described molecular fragments as isolobal "if the number, symmetry properties, approximate energy and shape of the frontier orbitals and the number of electrons in them are similar – not identical, but similar." One can predict the bonding and reactivity of a lesser-known species from that of a better-known species if the two molecular fragments have similar frontier orbitals, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). Isolobal compounds are analogues to isoelectronic compounds that share the same number of valence electrons and structure. A graphic representation of isolobal structures, with the isolobal pairs connected through a double-headed arrow with half an orbital below, is found in Figure 1.

The Jahn–Teller effect is an important mechanism of spontaneous symmetry breaking in molecular and solid-state systems which has far-reaching consequences in different fields, and is responsible for a variety of phenomena in spectroscopy, stereochemistry, crystal chemistry, molecular and solid-state physics, and materials science. The effect is named for Hermann Arthur Jahn and Edward Teller, who first reported studies about it in 1937.

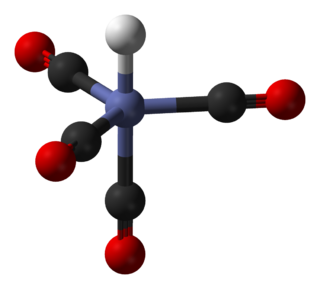

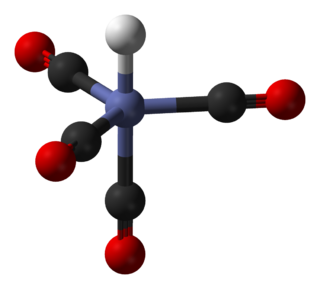

In chemistry, octahedral molecular geometry, also called square bipyramidal, describes the shape of compounds with six atoms or groups of atoms or ligands symmetrically arranged around a central atom, defining the vertices of an octahedron. The octahedron has eight faces, hence the prefix octa. The octahedron is one of the Platonic solids, although octahedral molecules typically have an atom in their centre and no bonds between the ligand atoms. A perfect octahedron belongs to the point group Oh. Examples of octahedral compounds are sulfur hexafluoride SF6 and molybdenum hexacarbonyl Mo(CO)6. The term "octahedral" is used somewhat loosely by chemists, focusing on the geometry of the bonds to the central atom and not considering differences among the ligands themselves. For example, [Co(NH3)6]3+, which is not octahedral in the mathematical sense due to the orientation of the N−H bonds, is referred to as octahedral.

A quintuple bond in chemistry is an unusual type of chemical bond, first reported in 2005 for a dichromium compound. Single bonds, double bonds, and triple bonds are commonplace in chemistry. Quadruple bonds are rarer and are currently known only among the transition metals, especially for Cr, Mo, W, and Re, e.g. [Mo2Cl8]4− and [Re2Cl8]2−. In a quintuple bond, ten electrons participate in bonding between the two metal centers, allocated as σ2π4δ4.

A quadruple bond is a type of chemical bond between two atoms involving eight electrons. This bond is an extension of the more familiar types of covalent bonds: double bonds and triple bonds. Stable quadruple bonds are most common among the transition metals in the middle of the d-block, such as rhenium, tungsten, technetium, molybdenum and chromium. Typically the ligands that support quadruple bonds are π-donors, not π-acceptors. Quadruple bonds are rare as compared to double bonds and triple bonds, but hundreds of compounds with such bonds have been prepared.

Copper proteins are proteins that contain one or more copper ions as prosthetic groups. Copper proteins are found in all forms of air-breathing life. These proteins are usually associated with electron-transfer with or without the involvement of oxygen (O2). Some organisms even use copper proteins to carry oxygen instead of iron proteins. A prominent copper protein in humans is in cytochrome c oxidase (cco). This enzyme cco mediates the controlled combustion that produces ATP. Other copper proteins include some superoxide dismutases used in defense against free radicals, peptidyl-α-monooxygenase for the production of hormones, and tyrosinase, which affects skin pigmentation.

The 18-electron rule is a chemical rule of thumb used primarily for predicting and rationalizing formulas for stable transition metal complexes, especially organometallic compounds. The rule is based on the fact that the valence orbitals in the electron configuration of transition metals consist of five (n−1)d orbitals, one ns orbital, and three np orbitals, where n is the principal quantum number. These orbitals can collectively accommodate 18 electrons as either bonding or non-bonding electron pairs. This means that the combination of these nine atomic orbitals with ligand orbitals creates nine molecular orbitals that are either metal-ligand bonding or non-bonding. When a metal complex has 18 valence electrons, it is said to have achieved the same electron configuration as the noble gas in the period, lending stability to the complex. Transition metal complexes that deviate from the rule are often interesting or useful because they tend to be more reactive. The rule is not helpful for complexes of metals that are not transition metals. The rule was first proposed by American chemist Irving Langmuir in 1921.

An electric effect influences the structure, reactivity, or properties of a molecule but is neither a traditional bond nor a steric effect. In organic chemistry, the term stereoelectronic effect is also used to emphasize the relation between the electronic structure and the geometry (stereochemistry) of a molecule.

The d electron count or number of d electrons is a chemistry formalism used to describe the electron configuration of the valence electrons of a transition metal center in a coordination complex. The d electron count is an effective way to understand the geometry and reactivity of transition metal complexes. The formalism has been incorporated into the two major models used to describe coordination complexes; crystal field theory and ligand field theory, which is a more advanced version based on molecular orbital theory. However the d electron count of an atom in a complex is often different from the d electron count of a free atom or a free ion of the same element.

Spin states when describing transition metal coordination complexes refers to the potential spin configurations of the central metal's d electrons. For several oxidation states, metals can adopt high-spin and low-spin configurations. The ambiguity only applies to first row metals, because second- and third-row metals are invariably low-spin. These configurations can be understood through the two major models used to describe coordination complexes; crystal field theory and ligand field theory.

Magnetochemistry is concerned with the magnetic properties of chemical compounds and elements. Magnetic properties arise from the spin and orbital angular momentum of the electrons contained in a compound. Compounds are diamagnetic when they contain no unpaired electrons. Molecular compounds that contain one or more unpaired electrons are paramagnetic. The magnitude of the paramagnetism is expressed as an effective magnetic moment, μeff. For first-row transition metals the magnitude of μeff is, to a first approximation, a simple function of the number of unpaired electrons, the spin-only formula. In general, spin–orbit coupling causes μeff to deviate from the spin-only formula. For the heavier transition metals, lanthanides and actinides, spin–orbit coupling cannot be ignored. Exchange interaction can occur in clusters and infinite lattices, resulting in ferromagnetism, antiferromagnetism or ferrimagnetism depending on the relative orientations of the individual spins.

In inorganic chemistry, the cis effect is defined as the labilization of CO ligands that are cis to other ligands. CO is a well-known strong pi-accepting ligand in organometallic chemistry that will labilize in the cis position when adjacent to ligands due to steric and electronic effects. The system most often studied for the cis effect is an octahedral complex M(CO)

5X where X is the ligand that will labilize a CO ligand cis to it. Unlike the trans effect, which is most often observed in 4-coordinate square planar complexes, the cis effect is observed in 6-coordinate octahedral transition metal complexes. It has been determined that ligands that are weak sigma donors and non-pi acceptors seem to have the strongest cis-labilizing effects. Therefore, the cis effect has the opposite trend of the trans-effect, which effectively labilizes ligands that are trans to strong pi accepting and sigma donating ligands.